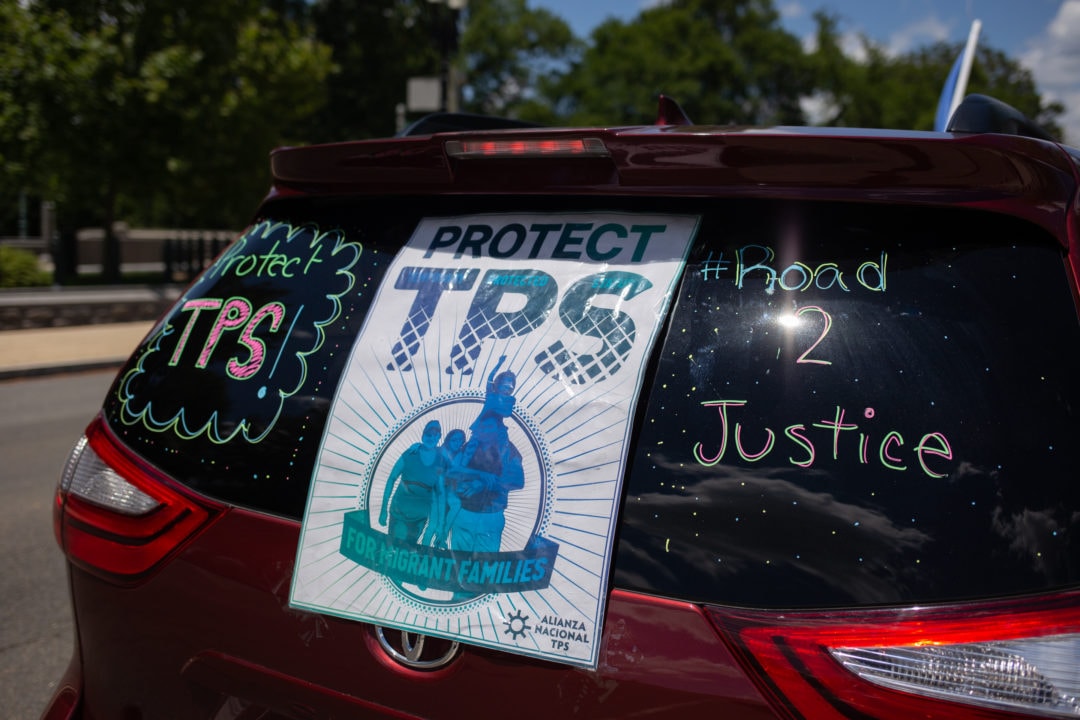

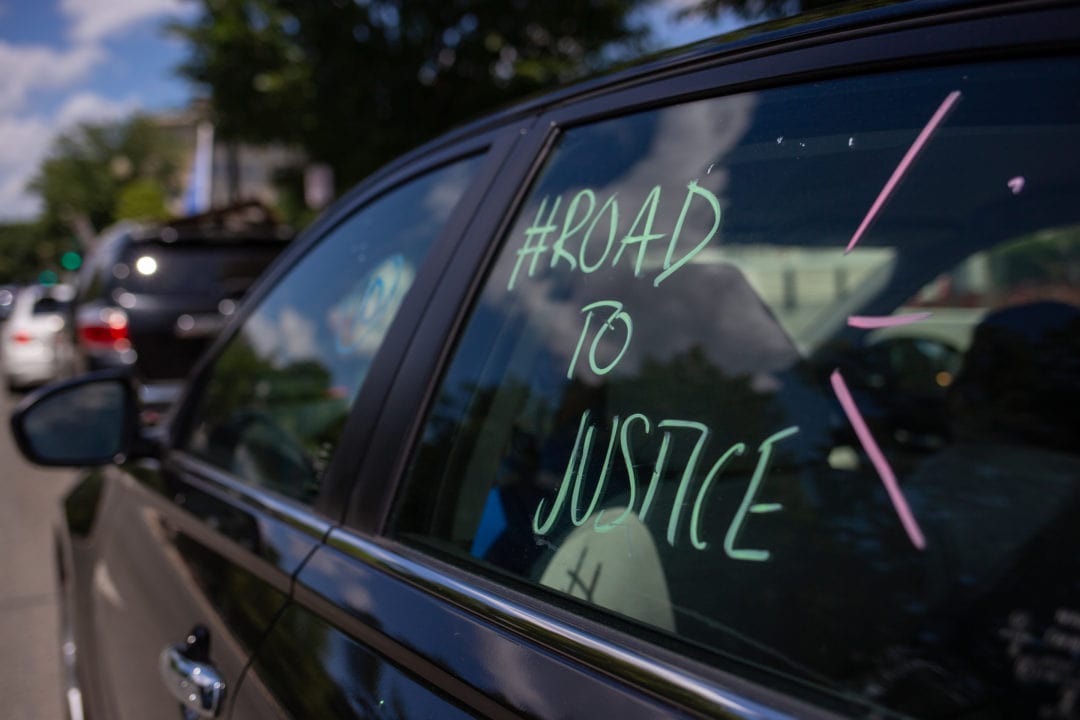

On a bright and sunny day at the end of June, a 200-car caravan inches slowly down First Street SE in Washington, D.C. More than 400 Temporary Protective Status (TPS) beneficiaries have driven their vehicles—decorated with colorful signs and slogans—from Maryland in an action coordinated by the National TPS Alliance.

Dubbed “On the Road to Justice,” the event takes place against a stark white background featuring the Capitol dome on one side and the Supreme Court colonnade on the other. Children pop through sunroofs and drivers flash peace signs in solidarity with those who are currently fighting for their lives—some in more ways than one.

Nearly 300,000 people around the U.S. are living with TPS, a designation given to residents of 10 countries around the world where conditions such as wars or natural disasters “temporarily prevent the country’s nationals from returning safely,” according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Beginning in 2018, the Trump administration announced that it planned to terminate TPS for beneficiaries from six countries, including El Salvador (65 percent of TPS holders are Salvadorian).

Last summer, more than 50 TPS holders piled into a bus printed with the words “Journey for Justice” on one side and the Spanish equivalent, “Jornada por la Justicia,” on the other. They embarked on a 12-week road trip across the U.S., stopping in 44 cities in more than 25 states. Faced with the threat of deportation and a pending court verdict, they hoped to harness the power of the great American road trip “to lift their collective voices against the termination of TPS, against the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of lawfully present immigrants, and against the criminalization of migration.”

-

Waving a flag in front of the Supreme Court. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

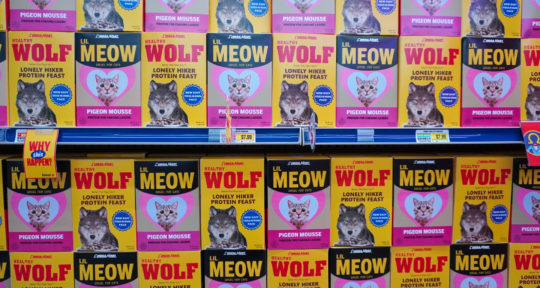

Each car is decorated differently. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A family pops out of their sunroof. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The cars drive slowly down First Street SE. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Cars from several states join the caravan. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The Road to Justice is just one of several actions TPS has planned for this year. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

More than 200 cars and 400 people participated in the car caravan. | Photo: Kristine Jones

The Journey for Justice

William Martinez, a regional organizer with the National TPS Alliance, was eight years old in 2001 when his family came to the U.S. after earthquakes devastated El Salvador. He was working as a construction supervisor in Virginia when a coworker told him that his TPS was about to be terminated. “I wasn’t really sure what he was talking about,” Martinez says. “But then my mom called me crying. It was very traumatic—I was working 70 hours a week, I had just bought a home, I was close to paying off my car. I had a lot of good stuff going for me. I had a really good life and now what?”

Martinez wasn’t alone; TPS beneficiaries formed the National TPS Alliance in June 2017, realizing the collective power of “advocacy efforts at a national level to save TPS for all beneficiaries in the short term and to devise legislation that creates a path to permanent residency in the long term,” according to the Alliance’s website.

The Journey for Justice bus left from Los Angeles, California, on August 17, 2019 and moved east. Martinez says that the original plan was to buy two buses—one for the West Coast and one for the East—but “money was tight” at the grassroots organization. Nonetheless, more than 40 separate National TPS Alliance committees across the U.S. and 10 affiliate non-profit organizations raised the $40,000 necessary to buy one bus.

Martinez, who lives in Maryland, flew to Michigan to board the bus in Grand Rapids. He had initially planned to join the Journey for Justice for just a week or two. But after sensing a rare opportunity to help out and hone his nascent public speaking skills—he speaks both English and Spanish fluently—he ended up traveling with the group for four weeks. “I knew if I didn’t stay on longer I would have regretted it,” he says.

In March, Martinez joined the National TPS Alliance full time; he says it pays less than his construction job, but he doesn’t mind. “Being with the Alliance I feel empowered,” Martinez says. “I didn’t feel empowered when I found out that TPS was being terminated. It was very traumatic, but what helped was just doing something. A lot of the people in Alliance have been empowered just by being involved.”

In the two decades since he arrived in the U.S., Martinez had traveled to Hawaii, Niagara Falls, and Florida, but the Journey for Justice tour took him through Minnesota, Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama, and North and South Carolina, in addition to Michigan. The bus—which featured colorful graphics of both the positive and negative realities of immigration in the U.S.—received mixed reactions. “We knew that some cities were going to be welcoming and some were not—but it was all part of the experience,” Martinez says.

At each stop, the Alliance held forums, press conferences, informational events, and committee meetings (or created new committees). They lobbied senators and representatives as part of the Alliance’s larger goal of eventually securing permanent citizenship for all TPS holders.

Feeling empowered

As long as there have been roads crisscrossing the U.S., people have found creative ways to use them—not only to physically connect to one another, but to attempt to bridge divisions of all kinds. The National TPS Alliance recognizes that it stands on the shoulders of those who were fighting for equality long before any of its members arrived in the U.S. The Journey for Justice bus stopped in Memphis, Tennessee, to tour the National Civil Rights Museum, located at the Lorraine Motel, and in Selma, Alabama, where the group marched across the historic Edmund Pettus Bridge.

“We recognize how important it is to learn about the struggles of the Black community [in particular],” Martinez says. “We have a responsibility to support other movements. It’s the reason why we have the rights to march or have a press conference in front of the Capitol—the results they get, we benefit from them. We are a better movement because of what others have sacrificed.”

-

The Jornada por la Justicia / Journey for Justice bus. | Photo courtesy of the National TPS Alliance -

TPS holders marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Alabama. | Photo courtesy of the National TPS Alliance -

TPS holders in Las Vegas. | Photo courtesy of the National TPS Alliance

In addition to spreading their message to non-immigrant communities, Martinez says the Journey for Justice brought together the TPS holders themselves—many of whom had no reason to join forces until they were bound by the looming threat of deportation. In addition to El Salvador, TPS holders originate from Honduras, Haiti, Nepal, Syria, Nicaragua, Yemen, Sudan, Somalia, and South Sudan; they reside in nearly every state in the U.S., including Puerto Rico.

“In Miami we met with Haitian communities, and Hondurans in the Carolinas,” Martinez says. “We may all come from Central America but we have different foods and different cultures. Sharing our cultures with each other was a light switch for our community—showing us that we’re all in this together.”

Essential now and always

In Ramos v. Nielsen, a court case currently awaiting decision in California, TPS holders have argued that the administration has no legal basis upon which to terminate the program’s protections. While they await the potentially life-changing decision, Alliance members have had to adjust their planned actions in the wake of COVID-19. A car caravan was the perfect way for TPS holders to mobilize while still taking the recommended social distancing precautions.

“We couldn’t just sit there during the crisis,” Martinez says. “We asked ourselves, ‘What can we do?’ and the answer was ‘work.’ Our health is at risk, yes, but so is our immigration status. The Alliance understood that we couldn’t just sit down and do nothing, so we mobilized people.”

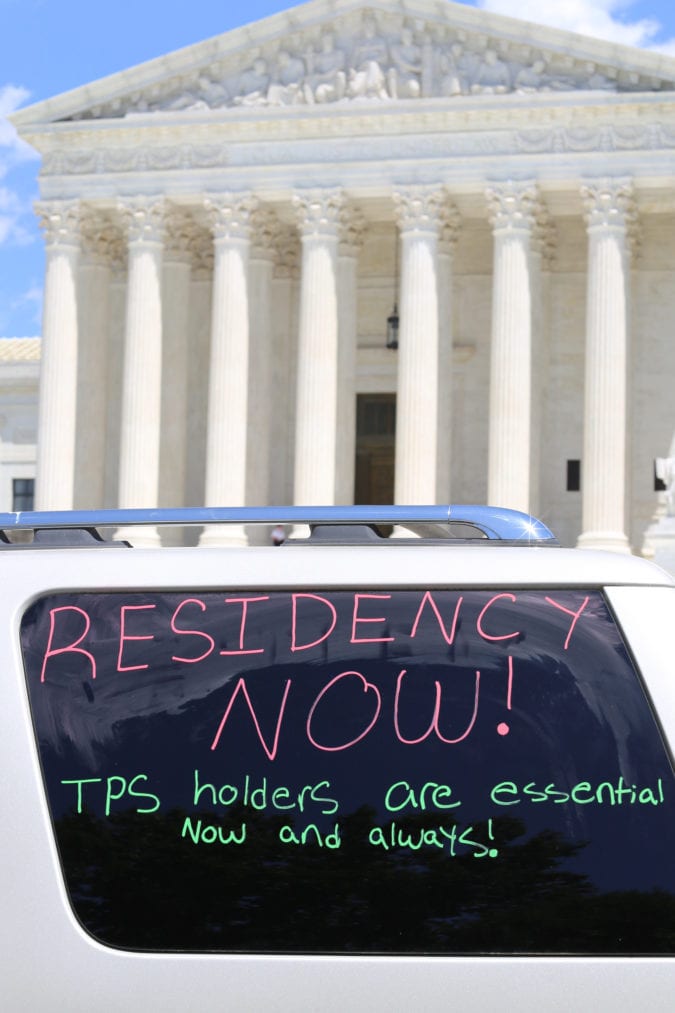

Around 130,000 TPS holders work in positions deemed “essential” during the pandemic. Hundreds of these workers participated in the caravan; they wore face masks and drove cars emblazoned with messages such as “If you accept our labor, accept our humanity,” and “TPS holders are essential now and always.”

The main goal of the Journey for Justice bus trip, the On the Road to Justice car caravan, and other Alliance actions is to raise awareness for the often-complicated immigration issues affecting hundreds of thousands of people currently living and working across the U.S. Martinez believes that most people are generally sympathetic to their plight, but simply uninformed.

“In every state we had opportunities to tell our stories over and over,” Martinez says. “People were surprised at the root causes of why people migrate to the U.S. They don’t know why these programs were created and we have a responsibility to inform the public why they shouldn’t be terminated.”

-

“If you accept our labor, accept our humanity.” | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

TPS holders come from 10 different countries around the world. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

“On the road to justice.” | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A driver flashes a peace sign. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Residency Now

In addition to sharing heart wrenching stories of forced separations and hardships, TPS holders share stories of triumphs—and a deep appreciation for their adopted country—that would be impressive under any circumstances. According to the National Immigration Forum, in the last decade, TPS holders in the U.S. have contributed $4.5 billion in pre-tax income annually to the country’s gross domestic product and $6.9 billion to Social Security and Medicare.

Some people, like Martinez, came to the U.S. as children and have had TPS for most of their lives. In that time, they’ve had children of their own (many of whom are U.S. citizens); they’ve earned college degrees, started businesses, and purchased their homes. Many no longer have meaningful connections to their countries of origin. They want U.S. citizenship only so they can keep doing what they’ve been doing since they first arrived: living their lives and contributing positively to their communities.

Regardless of how the court rules on Ramos v. Nielsen, Martinez says that the National TPS Alliance is just getting started. Their work will continue until everyone has “Residency Now,” a phrase painted on many of the cars in the caravan. The road to justice may be long, but that doesn’t mean it can’t also sometimes be fun. In fact, Martinez says that the Journey for Justice was such a life-changing experience, they’re planning to hit the road again in late September—this time for six weeks traveling in Midwestern and Southern states—for one final push before the November 3 election.

“Sometimes the narrative is that immigrants are a burden to this country, but in reality it’s the other way around,” Martinez says. “We contribute so much.”