Last summer, I drove 543 miles along Route 66, from Oklahoma City to Albuquerque, with a copy of The Negro Motorist Green Book in my hand. As I traversed regions of the country I had never seen—and once never imagined I would visit—I searched for some reflection of myself and my communities in the spaces I occupied. I wanted to believe that I belong on this highway, that even though these spaces weren’t built with people like me in mind, I too belong here.

In early 2016, Shing Yin Khor drove the length of Route 66—from Los Angeles to Chicago—with their dog, Bug. Khor, who uses they/them pronouns, immigrated to America from Malaysia when they were sixteen. While teens in the U.S. were watching MTV, Khor was watching American shows from the ‘60s and ‘70s. As a child growing up an ocean away, Khor envisioned “two Americas”—a glitzy, glamorous, high-end wonderland, or a Grapes of Wrath, Great Depression-esque hellscape. Khor believes this perception was likely influenced by their childhood fascination with U.S. history and the delay in the arrival of American media to South and East Asia.

Ahead of the trip, Khor thought the journey—one they had been dreaming of since they were a child—would be revelatory, that it would be a key that would unlock all of the secrets of America that were so unfamiliar to them. And, they planned to chronicle the journey and discoveries in a book once they finished their trip.

“I didn’t have a story when I set out on the trip,” Khor says. “I basically just trusted that the road would have stories, and it did. But it’s not the book I thought I was going to write when I first set out on the trip.”

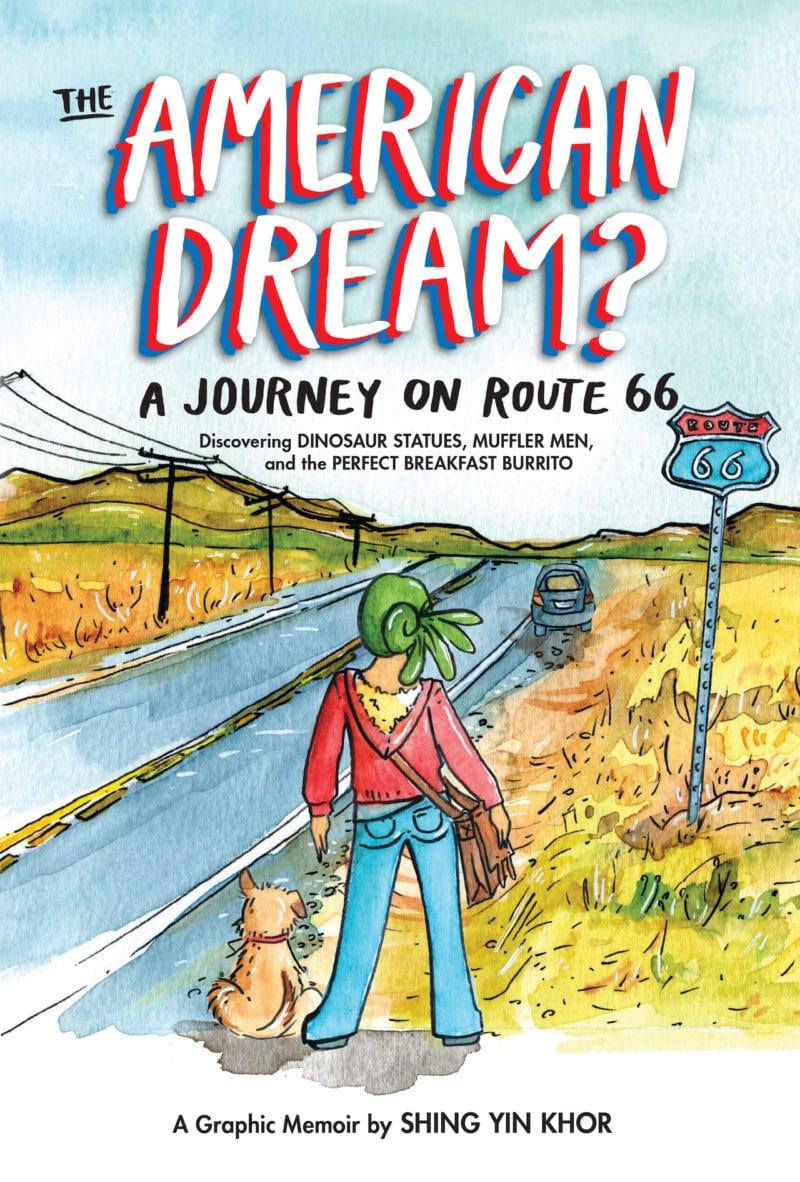

The American Dream?: A Journey on Route 66 Discovering Dinosaur Statues, Muffler Men, and the Perfect Breakfast Burrito is a graphic memoir—a work that combines intricately drawn panels with personal vignettes from the road. The book highlights the 2,448 miles of Route 66, including kitschy roadside attractions, small towns, big cities, internal monologues (which are common when traveling alone, Khor says), and Khor’s favorite Route 66 stop: Albuquerque. The book will be released on August 6th.

The mightiest muffler man

Khor says one of the most difficult parts of writing the book was coming up with the title. They settled on immediately presenting the reader with a question to contemplate: What is the American Dream?

“Ultimately, it’s very much a book about searching,” Khor says. “It’s very much a book about trying to find a place and trying to make sense out of my identity, but it’s not a book that ends with an answer to [the question].”

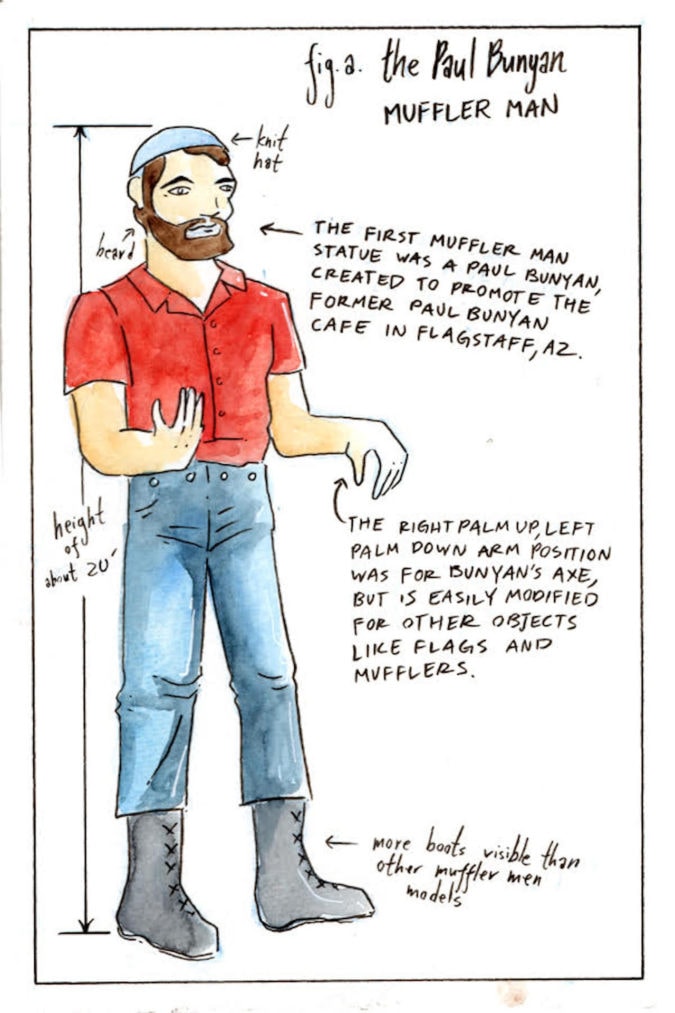

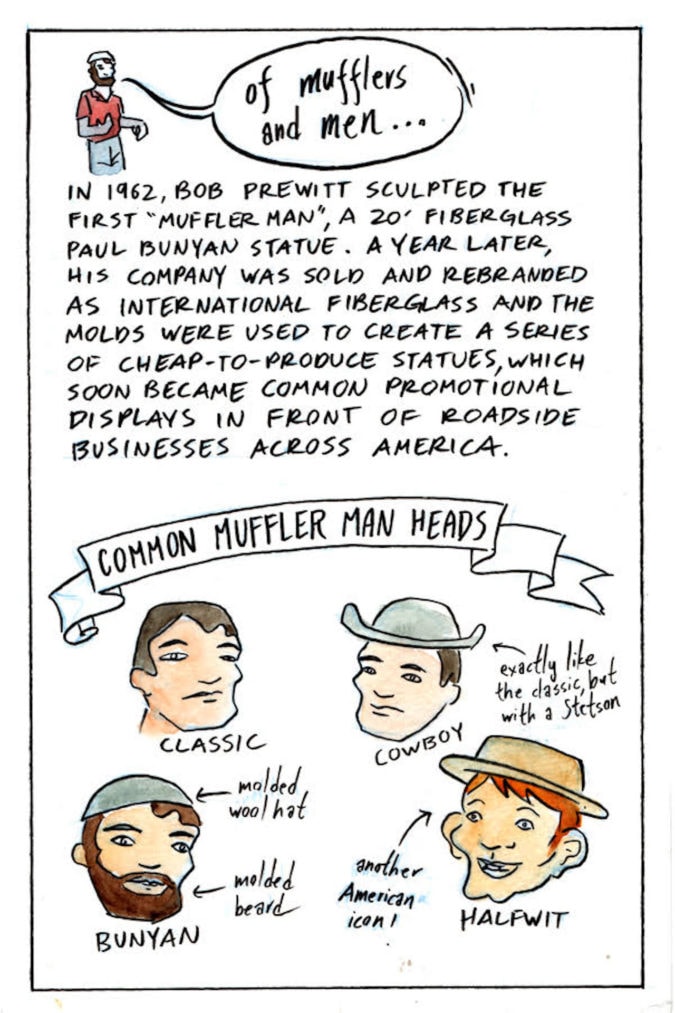

Khor loves roadside statues and muffler men so much that they decided to prominently feature both in the title of their book. But one folkloric icon stands out above the rest: Paul Bunyon.

The obsession started with a challenge. Several years ago, a friend challenged Khor to visit as many Paul Bunyon statues as they could in a two-year period. Khor visited about 30 statues, and their friend visited 40. (Today, Khor maintains a map of over 100 Paul Bunyan statues across America and Canada.) Though they didn’t win the bet, Khor says, “In the process, I ended up just researching and reading a lot about the Paul Bunyan mythos and its place in American history. Now it’s kind of become one of my major areas of research.”

Home on the road

In the two years since they wrote the book, Khor says their life has changed significantly. Since late 2016, they have driven portions of Route 66 again, written and illustrated several other forthcoming books, and become more politically and socially active. Still, Khor says they would not change the way the book turned out: “I have grown and evolved as a person and I do think that the book is a correct reflection of the person that I was when I took the trip.”

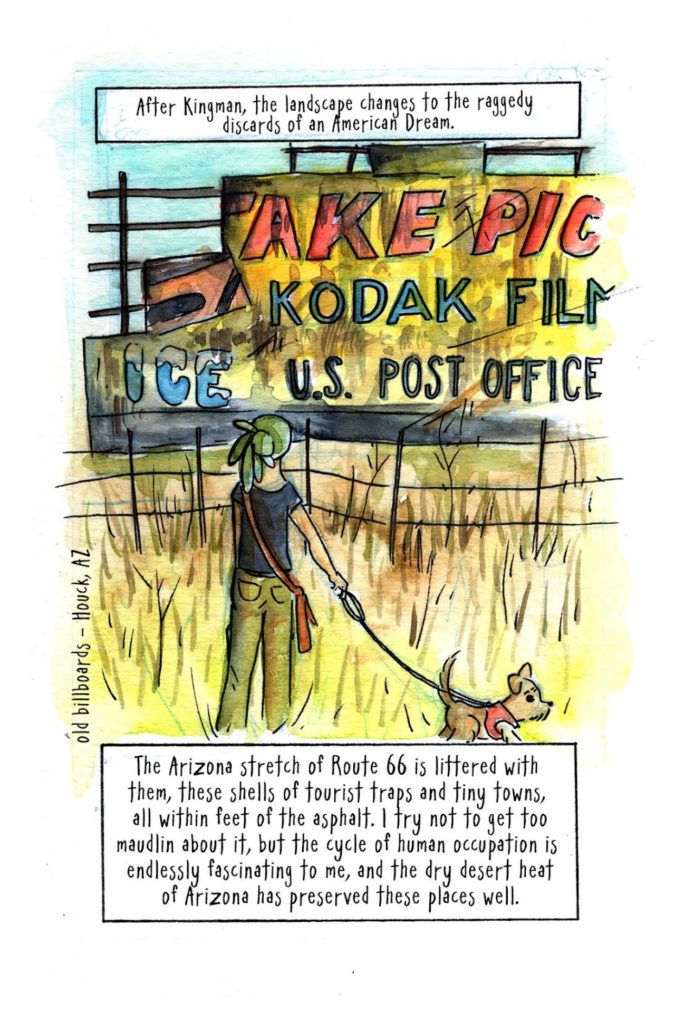

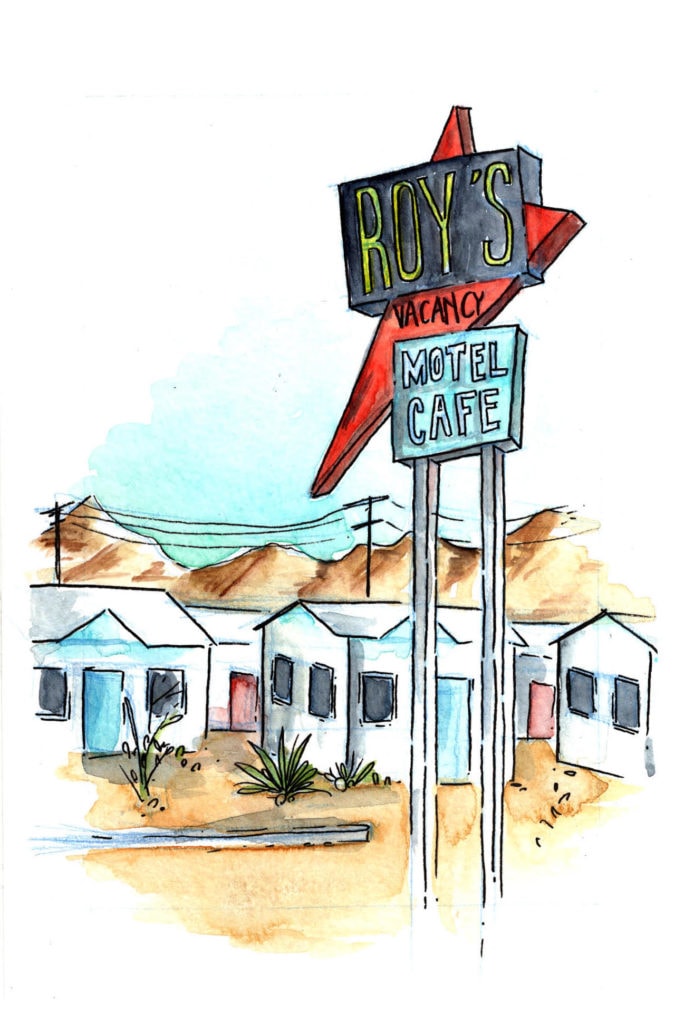

On the road, Khor was lonely, especially as a solo traveler in small towns devastated by the construction of I-40 in the 1960s: “I definitely felt this sense of desolation in many, many parts of Route 66, especially in the areas where the original road has been bypassed by a more significant freeway.”

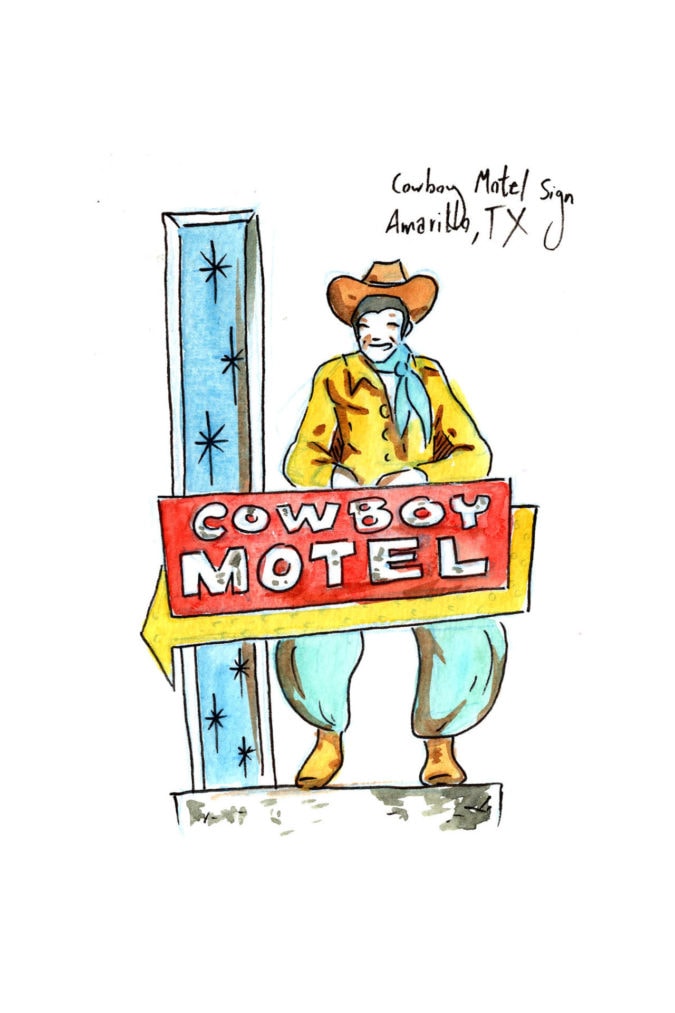

But, in the midst of such loneliness and searching, Khor found community and cultural connections in unexpected places. One of their favorite stops on Route 66 was Amarillo, Texas, where they were pleasantly surprised to learn that the city is home to one of the largest refugee populations in the country.

“I’m driving through Texas and I’m expecting very stereotypical Texas stuff. Are there going to be cowboys? Are there going to be a lot of steaks?” Khor says. “Yes—but in Amarillo, those cowboys are from Somalia.”

Refugee relocation in Amarillo is challenging the stereotypes of Route 66, and is producing an environment in which diverse new travelers are able to feel at home throughout the length of the Mother Road. For Khor, this taste of comfort and belonging came in the form of food: “At nine in the morning [in Amarillo], I had some of the best Burmese food I’d ever had while driving through an Asian market.”

For me, that sense of belonging revealed itself slowly, as I spent hot summer nights remaining still, taking time to absorb everything around me. Black children in Shamrock, Texas grinned at me as they biked by, racing to beat the street lights home. At the Acoma Pueblo, Indigenous guides shared stories of millennia of resistance and survival atop a 367-foot sandstone bluff. In Albuquerque, a South Asian family who immigrated from Tanzania welcomed me into the cool air conditioning of their motel to tell me about the journeys that brought them to this place. There is space for everyone—not just on Route 66, but all across America.

As a resident of Los Angeles, Khor says the trip affirmed all of the things they love about their home—its size, its breadth, and its people. But the trip also helped them recognize the beauty of smaller cities and small towns, from community networks to niche roadside attractions. Khor’s discovery of immigrant communities on Route 66 was an awakening. “That kind of restored my faith in a lot of America.”

Khor’s childhood vision of the U.S. proved to be untrue in their journeys—it does not merely exist as two poles. Places like Amarillo prove that it’s far more complex than that.

“I fundamentally understood that immigrants are everywhere in America, but actually seeing very clear roots planted in these places was incredibly heartening,” Khor says. “I was like, ‘Oh, good. We are everywhere.’”