When I arrive at the Rubell Museum, one of Washington, D.C.’s newest exhibition spaces, located about a mile south of the National Mall, I turn around and take in a surprise view of the U.S. Capitol. This stretch of I Street SW offers a different perspective from the one usually depicted on postcards or in movie montages: The Capitol’s iconic white dome juts out over a deserted playground and grimy interstate ramps, overshadowed by the brutalist concrete structures and brick smokestacks that loom over this less-touristy part of the District.

But it’s the perfect place for the new outpost of the Rubell Family Collection, which opened in Miami, Florida, 30 years ago. Renamed the Rubell Museum to represent “a new kind of institution serving as an advocate for a diverse mix of contemporary artists and a resource for both the public and art world to engage in a dialogue with them,” the D.C. location opened on October 29, 2022.

The colonial revival brick building in Southwest D.C. was built in 1906 as an elementary school and later expanded to house Randall Junior High School, a historically Black public school until 1978 (Marvin Gaye was a student at Randall in the 1950s). Minus the new glass entrance pavilion, the structure still very much looks like a school inside and out, even though it operated as a homeless shelter and artist studios in the decades after it ceased to be one—and that’s only part of what makes the Rubell such a compelling and crucial addition to the nation’s capital.

‘What’s going on’

Mera (a Head Start teacher) and Don Rubell (a physician and brother of Studio 54 co-owner Steve Rubell) married in the early 1960s and started collecting art in New York City. Together the Rubells have “built one of the most significant and far-ranging collections of contemporary art in the world,” according to Rubell Museum Miami. The still-growing collection contains more than 7,000 works of art from new and established artists.

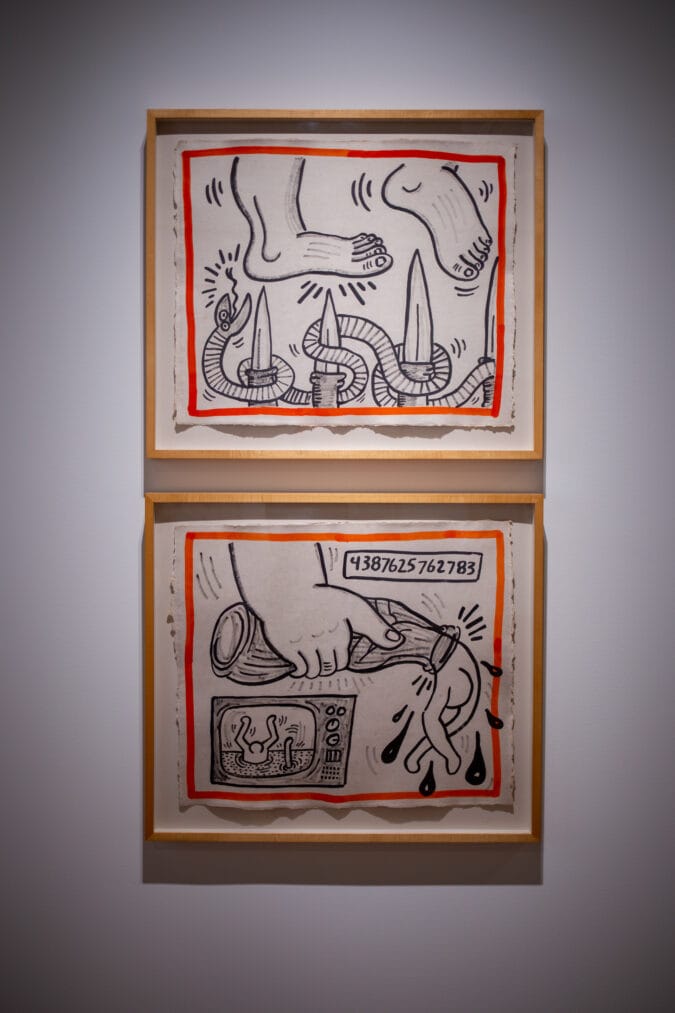

More than 190 of those pieces by 50 artists are currently on display in the D.C. museum’s inaugural exhibition What’s Going On, named for the 1971 Gaye album. The titular song plays on a continuous loop from a stereo on the floor in the gallery housing Untitled (Against All Odds), featuring 20 black ink drawings created by Keith Haring during a single day in 1989 (both Haring and Steve Rubell died from complications of AIDS within a year of the work’s completion).

In the handwritten introduction for the published limited edition of 20 Drawings Oct. 3, 1989, dedicated to the memory of Steve, Haring writes: “It’s very difficult (and against the basic principle of their existence) to explain the ‘meaning’ of my drawings. In this case, however, there may be a clue. During the first 2 hours or so, I was listening to Marvin Gaye’s classic album, ‘What’s Going On?’ over and over … Sometimes, music is ‘background’ for drawing, but sometimes it becomes an essential part of the creation of the work.”

Not just background

The Rubell Museum DC feels both radical and forward-thinking in its scope and vision, and already rooted in its historic location and new city; admission is free to all D.C. residents (the highest ticket price for non-residents is $15), and nearby a new 492-unit apartment building under construction will dedicate 20 percent of its units to affordable housing. The 32,000-square-foot school has been given a refresh, but still retains many of the details and layout of the original classrooms and administration offices.

“The museum’s historic setting in a place of learning invites the public to explore what artists can teach us about the world we live in and the issues with which we are wrestling as individuals and as a society,” says Mera. “As a former teacher, I see artists and teachers playing parallel roles as educators and in fostering civic engagement. With the preservation of this building, we honor the legacy of the Randall School’s many teachers, students, and parents.”

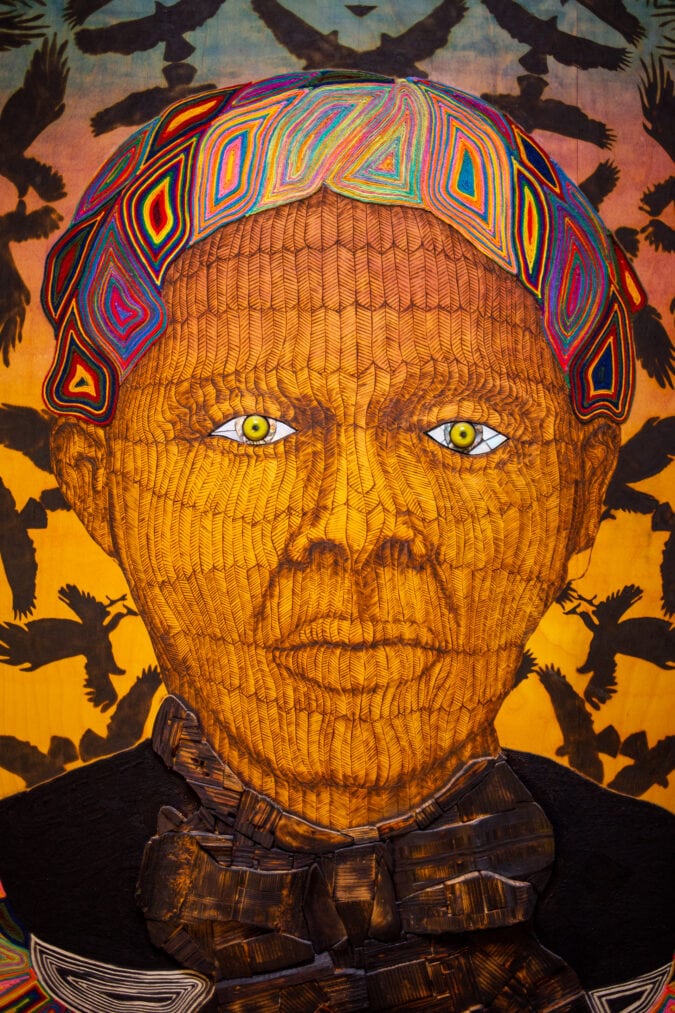

Sometimes, buildings are just “background” for museum collections, but the best structures are designed—or repurposed—to be an essential part of the experience. When I visit the Rubell on an early January afternoon, sunlight streams through the building’s arched windows, casting shadows on Vaughn Spann’s Big Black Rainbow (Smoky Eyes) in the expansive first gallery. The piece, made with polymer paint on terry cloth, is colorful, but also intentionally dark, its concepts and construction highlighted, rather than diminished, by its spacious surroundings: “I was thinking about color and its complexities in the U.S.,” says the artist in a statement displayed in the museum. “I wanted to put the blackness back into the spectrum.”

Nearby hangs a quilt depicting New York City’s public burial space, Hart Island, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; Another Man’s Cloth by El Anatsui looks like a flag from far away, but up close I see it is stitched not of fabric, but of flattened, undulating metal caps from discarded liquor bottles collected by the artist in Nigeria (a commentary on colonialism and consumption).

It’s hard to top Kehinde Wiley’s verdant portrait of Barack Obama, the highlight of the National Portrait Gallery’s collection of presidents, but the Wiley on display at Rubell DC is certainly bigger. It’s not hard to see why Obama chose and trusted Wiley with his official portrait. Created in 2008, Sleep is a traditional oil painting rendered meticulously on a massive 132-by-300-inch canvas. With conventional materials, Wiley depicts a scene that is anything but—at least in the white-centric classical European art he is referencing: a beautiful Black man reclining gracefully and resting peacefully.

‘Against all odds’

I first hear the Randall alum singing through the creaky floorboards above me while I’m in one of the lower level galleries: “There’s too many of you crying / There’s far too many of you dying … Oh, what’s going on?” I don’t understand the Haring connection until I enter that gallery later in my visit, but Gaye’s lyrics could have just as easily inspired every piece in the Rubell’s collection, comprising “artists who are responding to pressing social and political issues that continue to affect society today.”

There’s hope in Gaye’s lyrics, but also despair—and the cold comfort that comes with any great work of art that makes you feel both farther from and closer to the past, present, and future. Even the meaning of what counts as “contemporary” is always changing with new context. The Rubells have been a couple—and collecting art—for longer than a lot of the artists featured in their museums have been alive. You don’t have to live eight decades or more to see the connections across them, but it helps to have spaces and a collection as thoughtful as the Rubells’ to help expedite the process.

Haring’s introduction concludes by explaining what his drawings mean to him: “[They] are about the Earth we inherited and the dismal task of trying to save it—against all odds.” The panels that follow are full of knives, snakes, and Haring’s signature writhing, heavily outlined figures. Coupled with Gaye’s voice, the scenes and sentiment feel as relevant today as they must have in 1989, would have in 1889, or—if the Rubell has the longevity it deserves—will be in 2089. Throughout the galleries, the medium and messenger may differ, but the mission stays the same: “Oh, you know we’ve got to find a way / To bring some understanding here today.”