The salt came first. Even before coal mines pockmarked West Virginia’s Appalachian Mountains, 19th-century pioneers dug wells into a 400-million-year-old sea trapped beneath the Kanawha Valley. But the salt boom was short-lived, fading away after the Civil War. Today, only one local salt harvester remains: J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works.

When I visit J.Q. Dickinson on a trip to Charleston, there is no hint of the subterranean Iapetus Ocean in the forested road’s hills and hollows. I can understand how the co-owners, brother-sister duo Nancy Bruns and Lewis Payne, were unaware of their family’s defunct business until a decade ago. When J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works closed in 1945, it was the last of its kind. But in 2013, Bruns and Payne plunged back in, determined to resurrect the region’s salt heritage and redeem their family’s tangled antebellum roots.

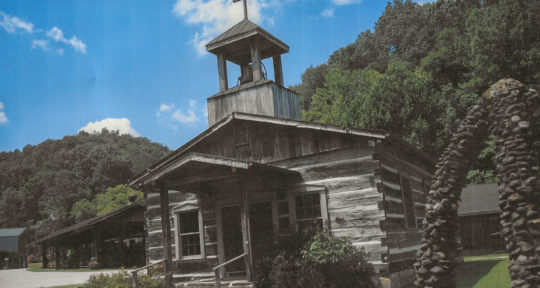

Pulling into the gravel parking lot, I notice how the modest farm above belies the giant aquifer below. A handful of greenhouses stand behind a rustic cabin, where Bruns steps out onto the porch to welcome me.

Behind the blue front door, there is a gift shop stocked with little jars of hand-harvested salt. I see heirloom salt flakes and smoked salt among salted caramels and chocolates. Bruns, a former restaurateur, manages the daily operations while her brother stays involved from afar. Like their forefathers, the duo takes the literal salt of the earth and spins it into something more.

Sustainable harvests

“We have seven generations of entrepreneurship,” Bruns says as we walk outside. In the distance, I see the property’s single pump siphoning primeval seawater topside. The siblings drilled the 350-foot well in 2013, basing the depth off of old farm records.

“It was really, really exciting,” Brun says. “It took longer than I thought it would, about three weeks. We had to get deeper through the salt layer, deep enough so there was no fluctuation in the level of the brine. We all had cups, and we were tasting the water as we kept going down—fresh, fresh, fresh, then finally, salty. That was a big day.”

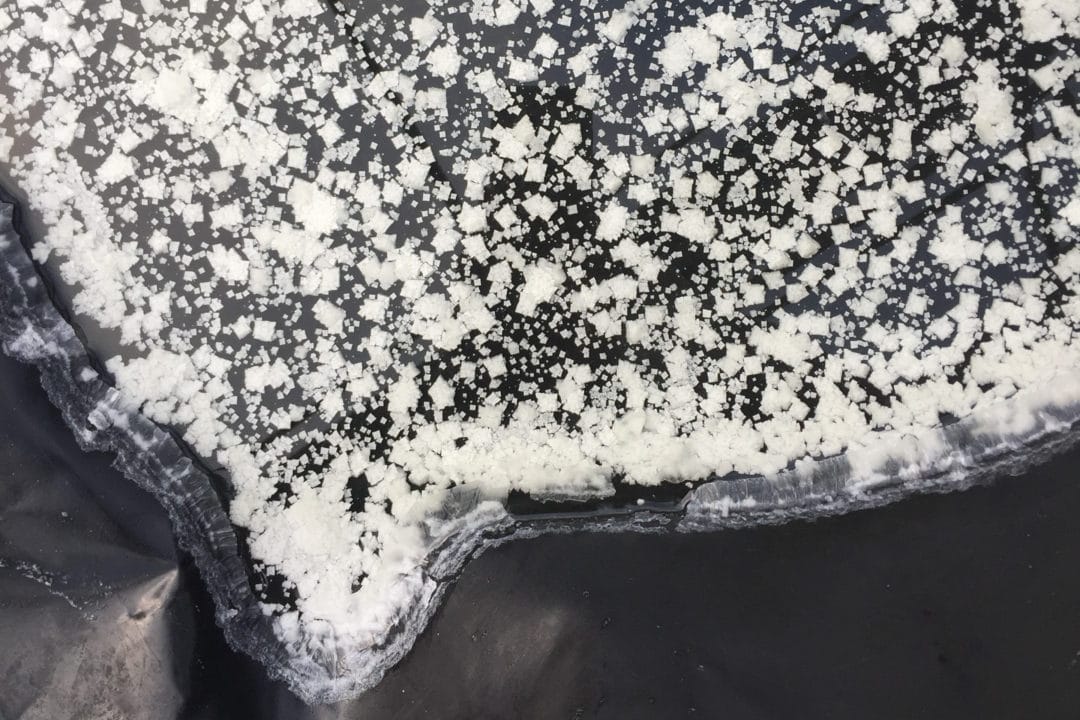

Today, about 7,500 gallons of brine are extracted from the earth each week. The brine flows into shallow pools inside one of three sun houses. From the series of pools, the salt is then harvested through solar evaporation.

We all had cups, and we were tasting the water as we kept going down— fresh, fresh, fresh, then finally, salty. That was a big day.

“It was very important to us that we were as environmentally sensitive as possible,” Bruns says. “The process takes 10 to 15 times as long as our ancestors’ stoking the coal and timber. But I know we’re doing it in the right way.”

Growing up, Bruns had heard only vague stories about her ancestors’ involvement in the Appalachian salt industry. She was in her 40s when she traced her genealogy to William Dickinson, who trekked over the mountains in the early 1800s in search of an underground fortune.

The more Bruns learned about the family salt business, the more she wondered what it would take for her to return to her roots. The dark, iron-heavy sea still existed beneath the property. Why not resurrect her family’s heritage?

“I was drawn to it magnetically, couldn’t get rid of it,” she says. “So I called [my brother] and said, ‘Here’s an idea.’ He didn’t take a lot of convincing.”

Facing the past

When we step into the first sun house, the air turns balmy. On summer days, the enclosures can heat up to 150 degrees Fahrenheit. I walk beside elevated pools of saltwater, awestruck by the perfect geometry of salt crystals clinging to the sides. Tiny salt flats emerge from rusty brine within five to 15 days, depending on the sunlight.

In the next sun house, Bruns rakes sparkling wet salt flakes into a small pile. She talks about why the salt empire of West Virginia dried up, leaving only J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works behind.

It started with a flood. In September 1861, the Kanawha River burst its banks, destroying several farms. Then, Union soldiers ransacked the saltworks as they pushed through West Virginia. The Civil War was a turning point, putting the salt boom’s ugly underbelly on display.

About 5,000 people were enslaved in the Kanawha Valley in the early 1800s. At its height, the Dickinsons kept 250 enslaved workers on the property.

“We were the largest slave owners in the valley at the height of the industry,” Bruns says. “That’s not something to be proud of. It wasn’t my decision, and that doesn’t make it OK, but it was the reality. We can’t change it and we’re not going to shove it under the rug and hide it in the closet with other skeletons. It should be out there and shared.”

The Kanawha Valley salt harvesters never recovered their antebellum success. They were too far from Chicago, the nation’s new meatpacking capital, and Confederate ties only facilitated the fall from grace. Only J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works eked out enough profit to stay open, but the business closed in 1945.

The best way forward

The J.Q. Dickinson Salt-Works of today is considerably smaller than its predecessor. Sun harvests require less manpower. After the brine has evaporated, the small staff—about a dozen employees—scrapes salt crystals into draining buckets. The buckets are transported to a final drying room fitted with dehumidifiers.

Wrapping up the tour, we stop by the processing room, the salt’s final stop. Staff members pause their work to smile and say hello. Their job is to sift through dried salt, removing any impure granules with tweezers. With tiny scoops, they fill each jar of salt by hand. I can’t help but contrast the quiet workstation with my image of its past. The same ancient aquifer supplies a very different Appalachian salt tradition today.

Bruns gives me a taste of salted caramel, which melts in my mouth as we walk back to the gift shop. I think about the history beneath my feet. Millions of years after tectonic shifts trapped the Iapetus Ocean, 200 years after imprisoned men and women hauled brine across Appalachian farms, a West Virginia family has managed to resurrect the sweetest parts of their complicated heritage.

The significance isn’t lost on Bruns. “I do [business] in the best way possible for our current times, the most sustainable way possible,” she says. “I’m doing my part, walking in my ancestors’ footsteps. I feel like my stars are aligned.”

If you go

J.Q. Dickinson Salt Works is open Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. from December 26 to April 29. It is open Monday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. from April 30 to Christmas. Free tours of the property are available from April to November. Visitors who book a $15 (per person) experiential tour can harvest salt, process it, and take home a small jar with their name on it. The property is also available for rent as an event venue.