“Would you like to sit on Baphomet?” asks the tattooed and black-clad guide at The Satanic Temple. He motions toward an 8.5-foot-tall bronze statue of a horned figure.

Also known as the Sabbatic Goat—a symbol of Satanism and the reconciliation of opposites—the bare-chested deity has wings and hooves, and sits beneath an inverted pentagram. Two children stand at Baphomet’s sides, gazing up at its beard in awe.

With an affirmative reply, I hoist myself up onto the creature’s lap. I mimic its pose—right arm raised and left one pointing down—in a reference to the Hermetic phrase, “As above, so below.”

The notorious Baphomet encapsulates the rebellious spirit of The Satanic Temple (TST) and the Salem Art Gallery, its headquarters in Massachusetts. Contrary to what many may assume, this isn’t a den of devil worshippers. Rather, TST’s mission is to encourage compassion and rational inquiry. The group makes headlines for confronting arbitrary laws that interfere with personal autonomy and disregard the separation of church and state. At their Salem gallery, I am stirred to action by the Satanists’ clever activism, and delighted by their collections of macabre art and literature.

Promoting pluralism

I speak with Lucien Greaves, the Satanic Temple’s official spokesperson. Greaves co-founded the temple with Malcolm Jarry in 2013, and TST’s provocative public campaigns coupled with a 2019 documentary, Hail Satan?, have raised its profile over the years.

“We have about 200,000 or more members at this point, and are growing rapidly,” Greaves says.

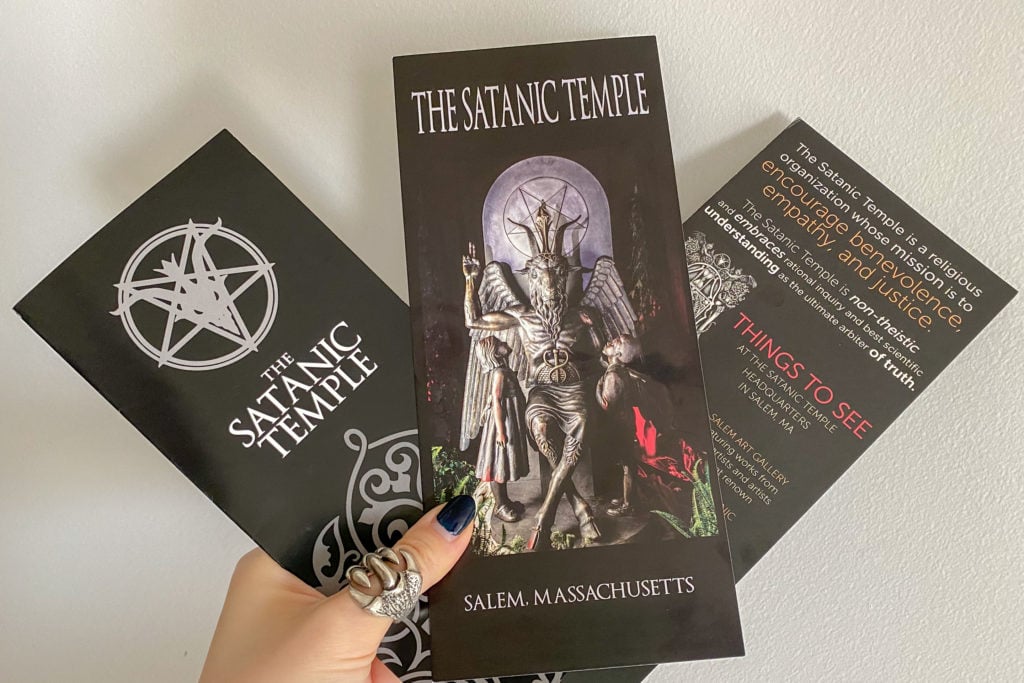

I examine an official pamphlet, designed like the Christian tracts that one of my aunts doggedly mails me every Christmas. The Satanic Temple, however, is a non-theistic religious organization. For members, Satan isn’t a supernatural being; he’s a symbol of rebellion against autocratic governments and unscientific thought. I flip to the “Seven Fundamental Tenets,” which outline TST’s humanistic values, including individualism, empathy, and justice.

In keeping with these guiding principles, TST has launched campaigns and lawsuits that challenge religious encroachments in public spaces, as well as affronts to bodily autonomy. They formed an “After School Satan Club”—complete with an activity book filled with pentagrams—to counter Christian “Good News” programs in public schools. To uphold pluralism, TST erected serpent and goat “nativity scenes” on capitol grounds, and members donned black robes to sing Satanic invocations at city council meetings.

“Satanists openly embrace the status of the outsider,” Greaves says regarding TST’s social activism. “Witch hunts past—as well as acknowledgement of witch hunts in the present—serves to remind us to remain vigilant in defense of the unjustly accused against mob intolerance.”

A former funeral parlor

The Satanic Temple opened its official headquarters in Salem in 2016. Greaves says that the location—in a town infamous for its witch trials and Halloween celebrations—was a natural fit.

The Satanists have painted the exterior of a former Victorian funeral home charcoal, and crowned it with a wreath shaped like their official sigil: a goat head over a pentagram.

“Ironically, I think Salem is one of the few places where The Satanic Temple could move in and establish a home without provoking a witch hunt.”

When TST first opened its doors, Greaves anticipated pushback from Salem residents. “However, the angry mob with pitchforks and torches never arrived, and we have been treated warmly by the community,” he says. “Ironically, I think Salem is currently one of the few places where The Satanic Temple could move in and establish a home without provoking a witch hunt.”

As I step into the Gothic dream home—adorned in blood-red drapery and damask wallpaper—I’m unsurprised to see drawings of baby devils, black cats, and skulls next to a curving staircase. But TST supporters are surprisingly diverse; medicine bags and dreamcatchers strung with stars have been donated by Kahnawake First Nation Mohawks.

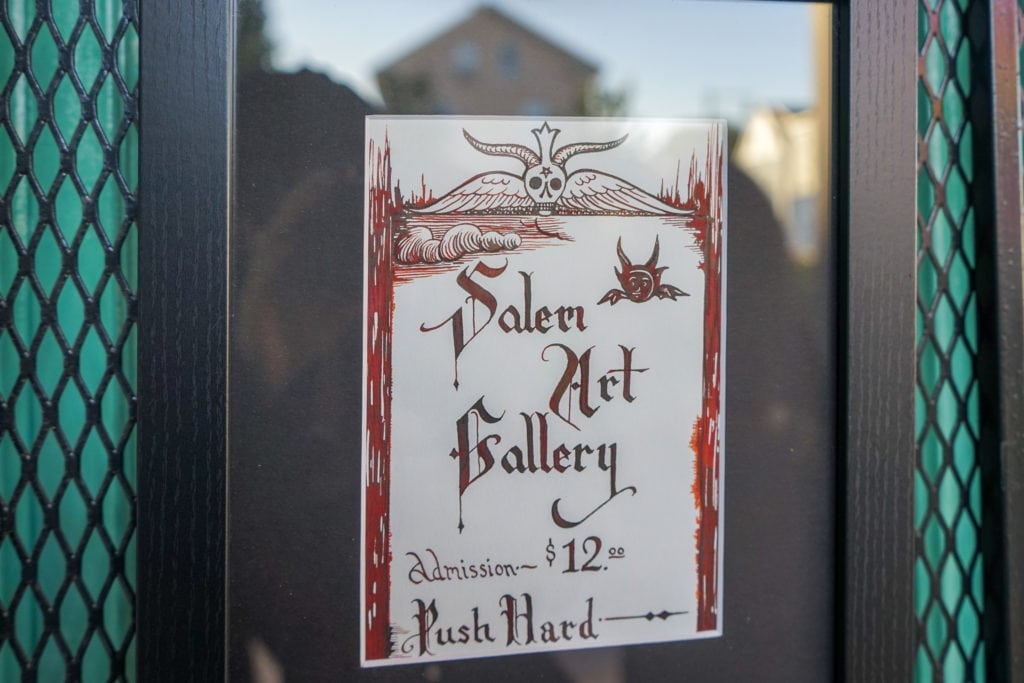

The space doubles as the Salem Art Gallery, which highlights artists drawn to darkness. Some of the art on display includes black-and-white photographs by William Mortensen, a master of monstrous compositions, and a wall of Ouija boards. On Greaves’ personal wishlist are works by Vincent Castiglia, an artist who paints full-canvas works using his own blood.

I pause by the Veterans’ Memorial, which TST commissioned to sit next to a Christian cross in Belle Plaine, Minnesota. The minimalist black cube—marked with gold pentagrams and topped with an upturned helmet—conveys a dignified power. Belle Plaine denied the Satanists the right to display their monument in the public forum, and the parties remain in a lawsuit over breach of contract.

But the star of The Satanic Temple is the 3,000-pound Baphomet statue that fills almost an entire room. Members had plans to place the winged goat on capitol grounds in Oklahoma, placing it next to a controversial Ten Commandments Monument in order to promote viewpoint neutrality, but the Oklahoma Supreme Court ordered the Christian monument removed before this could happen. The group currently has similar plans for Arkansas, which is being sued over the constitutionality of its Ten Commandments Monument. Until the case is resolved, “our legendary Baphomet is currently in the house, waiting for its moment on the Arkansas State Capitol grounds,” says Greaves.

A Satanic Panic library

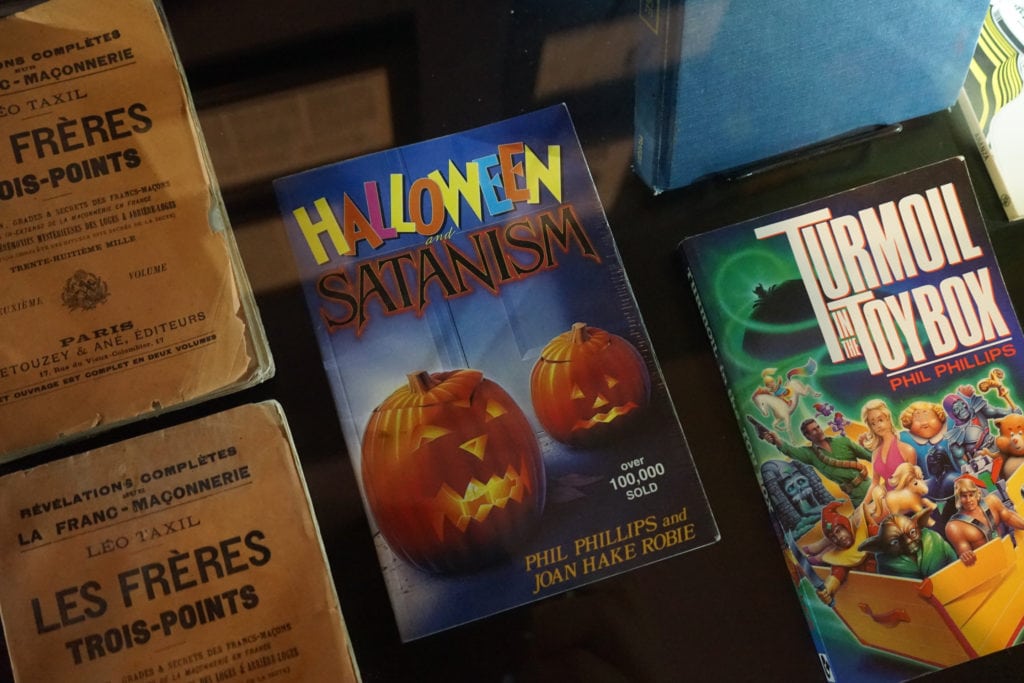

Upstairs, I peruse shelves of books with titles such as Satan’s Children and Evil Incarnate. Greaves says he’s been collecting books for a long time, and the library includes an archive about Satanic ritual abuse, or false claims of trauma drawn out in now-debunked psychiatric sessions.

“Our Grey Faction initiative actively fights against the propagation of Satanic Panic, pseudoscience, and modern-day conspiracy theories like QAnon,” he says.

On my way out, I browse the Satanic swag and can’t resist purchasing a tote featuring art by Greaves. “I Am a Friend of Satan,” it proclaims. In response to COVID-19, the community has built a virtual headquarters; Greaves has made his Patreon content free for the duration of the pandemic and he hosts an uproarious B-movie viewing and web chat every Saturday night on The Satanic Temple TV. “It has developed a fairly faithful following of viewers who seem to enjoy offering commentary on horrible films as much as I do,” he says.

Although the pandemic has halted many of Greaves’ plans—including speaking engagements and touring with his band Satanic Planet—he says his organization has no time for idle hands. The Satanic Temple persists in its efforts to raise hell against oppressive institutions, while advocating for social justice.

No matter what the future holds, “The Satanic Temple will keep fighting for pluralism and in defense of true religious liberty,” Greaves says.

If you go

The Satanic Temple and Salem Art Gallery is closed for the season. Visit their Instagram for the latest information.