Coal is controversial. Once the backbone of the U.S. economy, it’s now an industry in decline, loathed by the eco-conscious and inextricably linked with the devastating effects of climate change. As a born-and-bred Ohioan, I’ve recently felt a pull to learn more about the coal industry—and, more specifically, those who get left behind when mines close and companies move on to different regions or technologies.

The economy of the Rust Belt boomed during the Industrial Revolution, then plummeted in the 1980s. Coal was one of the industries hit the hardest—a win for the planet perhaps, but not necessarily for the thousands of people once employed in mines all across the country. Many communities haven’t yet recovered, and people feel forgotten, ignored, and isolated.

The Ruins Project, a former coal mine upcycled as a mosaic art installation, attempts to preserve some of these coal miners’ stories. Located an hour southeast of Pittsburgh in the former Banning No. 2 mine, the open air art museum documents southwest Pennsylvania’s deep mining history. At any given time between 1891 and 1946, 600 workers filled this mine owned by Pittsburgh Coal Company; thousands upon thousands worked here over its 55 years of operation.

“Being not just a mosaic artist, but having a history of coal mining in my family, I really care about this part of the story,” says The Ruins founder and mosaicist Rachel Sager. “These people were left behind when the coal companies shut down. There was a story that wasn’t being told in a powerfully artistic way, and I felt like this was an opportunity that fell into my lap.”

Transcending politics

Sager grew up just minutes from the Banning No. 2 mine. She leads small guided tours, like the one I’m about to join, for roughly one hour throughout The Ruins. As the final guests arrive, Sager gathers the group and kicks things off with an anecdote no one in the crowd is expecting.

“So, I bought a coal mine by accident,” she says, laughing. Just steps from Pennsylvania’s Youghiogheny River, Sager had long admired this charming property for its natural beauty. The water trail is slowly rebounding from years of industry degradation, and the Great Allegheny Passage, a 150-mile multipurpose trail from Pittsburgh to Cumberland, Maryland, completed in 2007, winds along Sager’s front yard.

When Sager finally came to terms with the fact that her waterfront property also included an old coal mine, her artistic vision came into focus. “My head quickly saw it as a giant cement canvas just waiting there,” she says as we enter The Ruins.

The maze of dilapidated concrete walls is only a fraction of what once stood here. As we walk through the property, admiring tiny colorful tiles that tell significantly larger stories, I feel none of the awkwardness I expected inside of a coal mine. Just the mention of coal—which Sager says has become a “four-letter word”—can morph conversations into an “us-versus-them” debate with no easy solutions. But, “The Ruins transcends politics,” Sager says. “It’s about making a connection where there’s a disconnect. People often don’t even realize they’re part of coal’s whole big infrastructure.”

One piece at a time

Pointing to an intricate mosaic map, Sager describes some of the miners who used to work here. “This was the quintessential American melting pot, with a lot of first-generation Eastern European immigrants,” she says. “I used colors to represent all of these different people—the cultures coming together to do this job.”

The Ruins keeps this melting pot alive with the help of an expansive network of mosaicists—Sager works with artists from 14 states and five countries. Those who can visit in person work onsite, but artists also send their mosaics on mesh. “They become a Ruins artist without ever stepping foot here,” Sager says, noting that many of the mine’s 40 mosaic birds were created this way.

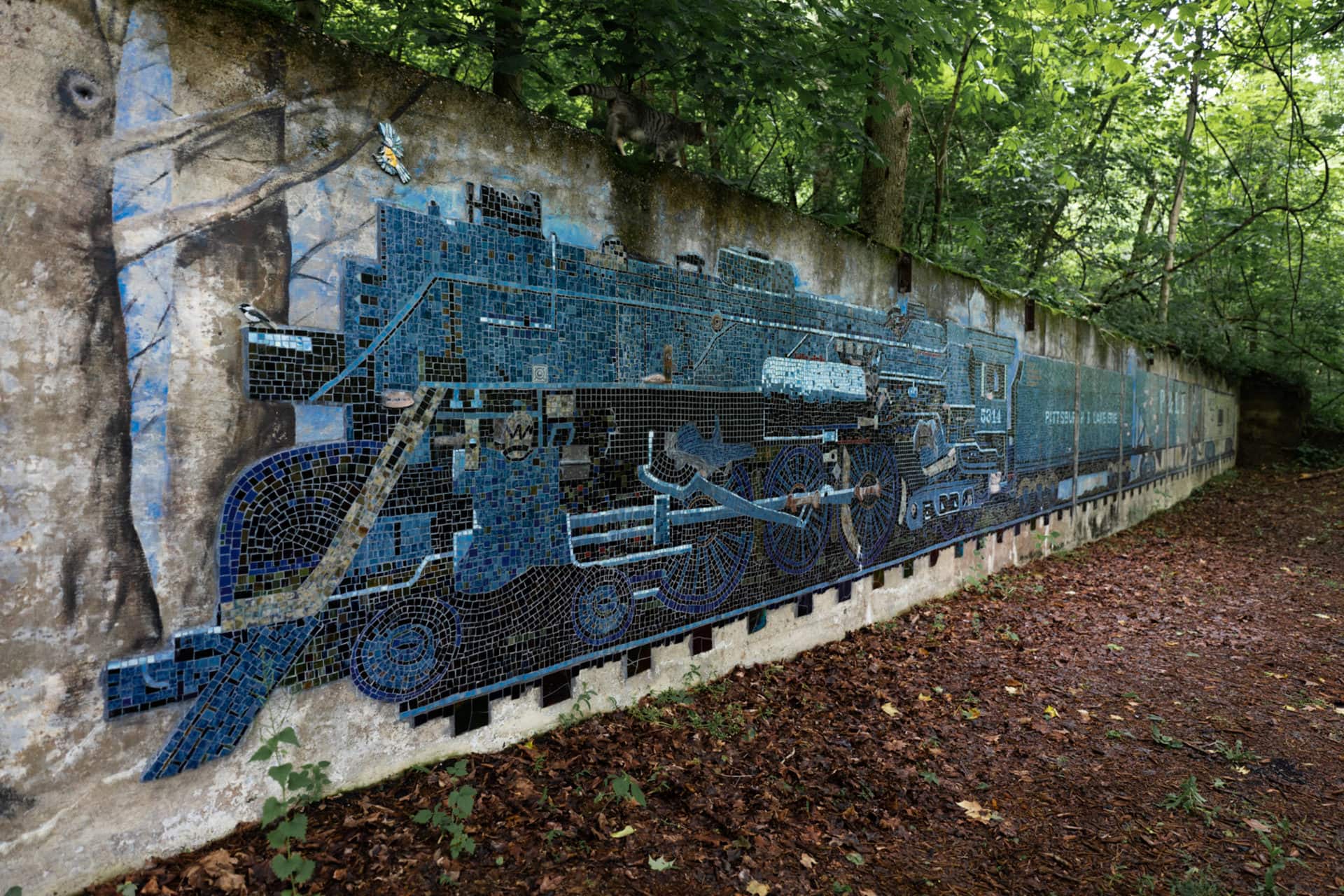

One standout is The Ruins train, crafted by Pittsburgh mosaic artist Stevo Sadvary with the help of a GoFundMe campaign. This massive depiction of a Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad steam locomotive, used to transport coal, is an impressive mosaic masterpiece that spans 67 feet. “[Sadvary] comes from a similar coal history as I do,” Sager says. “When I realized how big his vision was, I gave him the longest wall we had. It took three months, and he did this pretty much all by himself, one piece at a time.”

Conversations and connections

After appreciating Sadvary’s work, we round the corner to another striking scene: what looks like three men painted on a series of crumbling concrete walls. Except, upon closer inspection, these intricate pieces aren’t paintings, but astonishingly precise mosaic portraits. Sager says this area was inspired by the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., and the man on the right is her father, who passed away last year. “It’s not just sentimentality,” Sager says. “He was a coal miner, and none of this would exist without his influence on me. He helped me see all kinds of things—the ground beneath my feet, the layers of the earth.”

Our group pauses for an unplanned moment of silence, a chance to honor Sager’s father and the countless other similar stories these broken walls could tell. It’s only then that the depth of The Ruins experience hits me. She may have purchased it by accident, but through this dilapidated coal mine, Sager has built a bridge for potential connections—and a chance for visitors from all backgrounds to understand these often-maligned communities. Beyond the politics, there are always people.

Sager knows that not everyone may agree, but she says it’s important to try anyway. “My goal is to illuminate and inspire, to get people to think about what happened before us,” she says as we exit the mine. “You can come here knowing the story, or come here knowing absolutely nothing, but coming here with an open mind is important.”

If you go:

The Ruins Project is open year-round. Tours (given to a minimum of three people and a maximum of 20) are available by appointment only and last about an hour. Tickets are $15 per person.