If trees got together and talked about where they could find a good party, I think they’d all agree on Michigan. It’s a bushy wilderness enveloped in forests, fed by an ecosystem of lakes, great and small. The human population is scattered, leaving plenty of room for the trees to spread out, pair up, and cross-pollinate. The humans who do call Michigan home are of a solitary breed, too: hunters, bird-watchers, camping enthusiasts, wilderness explorers.

Despite being born and raised in northern Michigan, I am none of those things.

Yet somehow, as a returning visitor to my home state, I saw something I had never seen before. Heading through a tunnel of trees on the Blue Star Highway, I turned a corner and dark branches began to sparkle in the headlights. One disco ball after another glittered alive. It was a queer rainbow in the forest, hidden in plain sight.

Michigan for Alaska

In the summer of 2015, I joined a tiny team of indie filmmakers from Los Angeles on a remote location film shoot in southwest Michigan. Shedding my Michigan origins for the all-too-common California dream, I was working as a freelance set decorator and prop master in Los Angeles when my favorite production designer-boss, Michael Fitzgerald, brought me on as prop master for a movie filming in Michigan. “Do you want to work on a movie about a drag queen boxer in Alaska?” asked Fitzgerald. Michigan would stand in as a less-remote alternative to Alaska.

The hero of Alaska is a Drag, Leo, is a black teenage boy caught between his dream of becoming a drag star and his talent as a boxer. The fish-out-of-water story mashes a hyper-masculine sport world with a misfit kid who loves costumes and vogueing. His fantasies involve lots of disco balls. In the end, he gains acceptance by embracing both sides of his identity.

As an artsy kid and starting player on the high school basketball team who never fit in with the hunters and campers, I recognized myself in Leo’s story. When I moved to Los Angeles, I quickly fell in with a small art department team after being hired by a pair of tattooed, feminist lesbians who produced bizarre low-budget movies. That’s how I met Fitzgerald, a gay theatre kid from a surfing town, and the leader of the art department. We went on to make low-budget films with characters not typically depicted in Hollywood movies: quirky women, transgender sex workers, underworld immigrants, black chess champions, religious minorities, and, of course, drag queens. So many drag queens.

Naturally, I said yes to the project and accompanied Fitzgerald, plus our set decorator and the rest of the team, to Michigan. As the only straight person in our Alaska art department, I wondered how accepting southwest Michigan, known for its conservative, Dutch Reformed Church communities, would be of the rest of my tribe.

Camping is a virtue

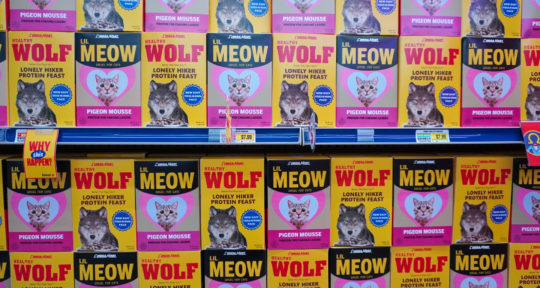

We spent our first days looking for props and set decorations up and down the Lake Michigan coast. Bait and tackle shops, local hardware stores, and boxing gyms were not hard to find. We tested several versions of our story. “It’s a movie about a kid who works at a fishing cannery and does boxing,” I explained to burley bait-and-tackle guys. When we visited thrift shops, many run as church missions, in search of disco balls, glittery costume jewelry, and ‘80s prom dresses, that line didn’t cut it. “He also likes to vogue,” I told the friendly cashier in a thrift store that raised money for shelter cats and sent Bibles to Mexico. To my surprise, she just smiled.

Fitzgerald started a gay-friendly recon mission even before we arrived, finding CampIt, a gay RV park outside of the town of Douglas, and The Dunes, its sister site in Douglas. Both were about a thirty-minute drive from our core location in South Haven. A few regulars from CampIt joined our crew as construction coordinators and transportation supervisors. Michael O’Connor, CampIt’s owner, quickly became Fitzgerald’s go-to local. The performers came from summer drag shows coordinated by The Dunes and CampIt.

We made our way to the tunnel of trees one night. Once I saw the disco balls, I knew we were home.

From the outside, The Dunes looks like a woodsy log cabin, familiar and non-descript. The drag queen bouncer at the door invited us inside, where more disco balls, bare-chested bartenders, and Madonna beats awaited.

We had come straight from a day on set, all wearing way too many clothes and not enough glitter, so it took me a minute to adjust. We walked around the main bar, appreciated the leather, and surveyed the outdoor pool and patio. It was packed. “I had no idea Michigan even had gay people,” I naively told Fitzgerald. He raised an eyebrow.

We’ve always been here

Saugatuck and Douglas are twin villages of about 1,000 residents each that sit on either side of the Kalamazoo River, an inland waterway feeding Lake Michigan. Victorian homes, summer boats, Dutch Reformed churches, and American flags line the streets, like they do at so many other tourist towns along the Lake Michigan waterfront. But Saugatuck has something different in its past. In the summer of 1907, students from the Art Institute of Chicago took over a local inn and started a tradition of summer residencies in Saugatuck that has continued on for more than a century.

Defying a local anti-gay ordinance that restricted the sale of alcohol to LGBTQ people, a few bars catered to a queer clientele—including the Blue Tempo, where Carl Jennings worked as a bartender in the 1970s. When the bar burned down in 1979, Jennings and his partner, Larry Gammons, decided to fulfill their dream of opening an LGBTQ hotel. Despite Saugatuck’s progressive history, the city refused to sell them property. Instead, they found a 22-room motel on the other side of the river, in Douglas, which became The Dunes.

Soon, the freshly-minted hoteliers expanded the humble accommodation with a dance floor, more rooms, and cottages. The Dunes hosted entertainers like Eartha Kitt, making it a magnet for under-the-radar culture that one certainly wouldn’t find elsewhere in conservative west Michigan.

“They even let porn studios film there,” says Mike Jones, The Dunes’ current owner. “It became a gay safe haven in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. People in small towns never had anywhere to go and be gay, so they could come here.” That’s how Jones and his two partners, who lived in Chicago at the time, found The Dunes. They bought the property from the retiring Jennings and Gammons in 1999.

Taking center stage

By the time we arrived on the scene, The Dunes had already helped shape the LGBTQ community in southwest Michigan for 35 years with events for all kinds of unique, niche subcultures. “We have theme weekends for bears, leather weekends, lesbian weekends. There’s something for everybody who wants to celebrate with their peeps,” Jones says, noting that neighboring towns are friendly and open to the gay community here.

“People in small towns never had anywhere to go and be gay, so they could come here.”

In Saugatuck and Douglas, “there are a lot of gay people on city counsel, people who own businesses. The Dunes is the only place with a primarily gay market, but a lot of other places are gay-friendly,” he says, noting the social acceptance his community finally enjoys in a place he’s called home for more than 20 years. “Two weeks ago, the town had its first Pride event. So many businesses put up Pride flags for the month, which has never happened. Downtown Douglas just painted its first rainbow crosswalk.”

Jones finds that his older clientele likes to come to The Dunes to escape the chaos of big-city Pride, opting instead for the more relaxed atmosphere. Jones has a vision for a Saugatuck-Douglas Pride that celebrates diversity in its own way. “Since we have such a unique community, the Pride here needs to find its own voice that celebrates our unique community amidst the Christian-reformed community,” he says.

Since the Stonewall Riots, commemorated during Pride, LGBTQ people have been fighting for legal and social equality. Today, the strength of Pride is its broad sense of diversity and intersectionality, which includes all kinds of marginalized people.

Wandering through the club that night, we found a hidden den for the most subversive characters: the karaoke singers. Whispering to the queen onstage, I requested my song, Tammy Wynette’s “Stand by your Man.” As I belted out the lyrics to the room, my team of movie friends at my side, I was happy we had found our way to Michigan together. In our Alaska is a Drag tribe that summer, “queer” meant acceptance, family, and love. In a word, Pride.