Just east of downtown Denver, on a raucous stretch of Colfax Avenue, the neon and fluorescent lights of Tom’s Diner glow 24 hours a day. It’s not the Tom’s Diner from the Suzanne Vega song of the same name (that one’s in New York City), but it may as well be: At any given hour, you’ll find a melting pot of patrons eating and chatting, absorbed in books or sipping coffee among its stone walls, vaulted ceiling, and naugahyde booths.

The diner, opened as part of the now-defunct White Spot chain in 1967, has remained more or less unchanged for decades. It’s a meeting place and anchor of its neighborhood, but now the diner’s owner and namesake, Tom Messina, is ready to hang up his apron and sell the farm. Thanks to the red-hot Denver real estate market, Tom’s historic building could soon meet the wrecking ball.

Neon glow at night. | Photo: Tag Christof Booth, screen, and fern. | Photo: Tag Christof Tom’s clock. | Photo: Tag Christof The counter. | Photo: Tag Christof

Designed by Armet & Davis—the definitive architects of mid-century Space Age coffee shops—the structure is a solid example of Googie architecture, and arguably its best surviving example in Colorado. The firm, known these days as Armet Davis Newlove, is best-known for a few still-standing Southern California icons such as Pann’s Restaurant and Johnie’s Coffee Shop (the latter has been transformed into “Bernie’s Coffee Shop” while it serves as a meeting spot for organizers for Senator Bernie Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign).

An uncertain future

Though Pann’s, Johnie’s, and a handful of other diners are now protected by historic designations, scores of other Googie icons around the country have been demolished. In recent years, thanks to the growth of online communities of modern architecture enthusiasts, these one-of-a-kind places have achieved a sort of mythical status, and support for their preservation has grown dramatically.

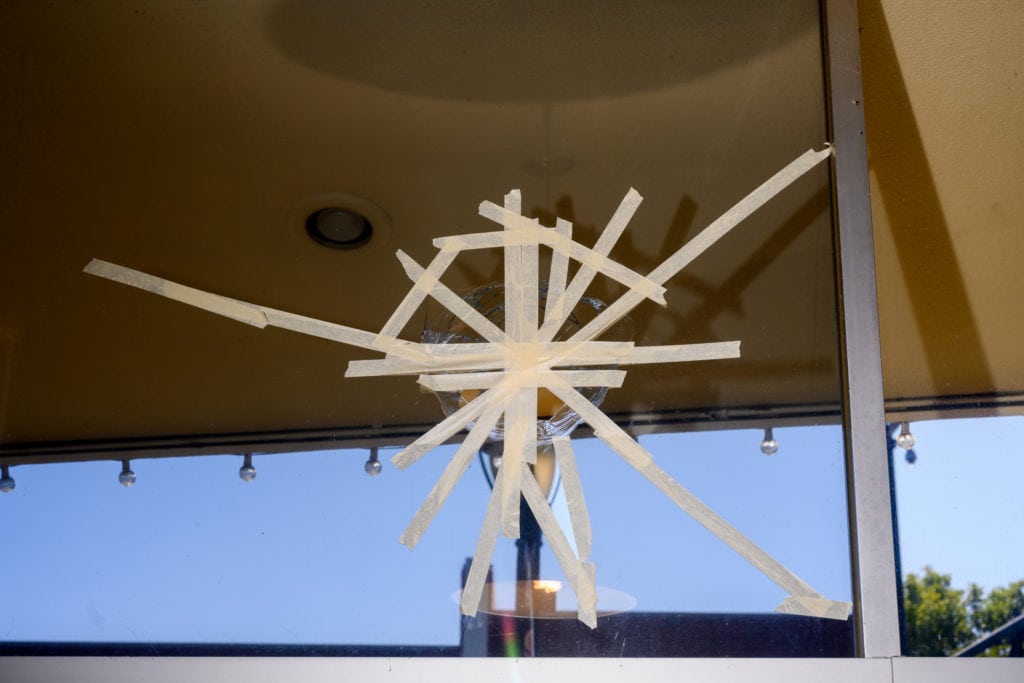

The exterior at night. | Photo: Tag Christof DIY patch job, after someone on Colfax threw a rock at the plate glass. | Photo: Tag Christof A vinyl booth. | Photo: Tag Christof

When news of the potential loss of Tom’s historic building spread earlier this year, local community members banded together with the help of preservation nonprofit Historic Denver to lobby for a binding protected status. The grassroots campaign was ultimately unsuccessful and the impending closure of Tom’s means that any future developer can bulldoze the structure to make way for anything they wish that will extract maximum profit from the land. These days, in burgeoning cities like Denver, that almost always translates into a generic block of market-rate luxury apartments.

According to Annie Levinsky, executive director of Historic Denver, “The city issued a Certificate of Non-Historic Status, which means that the building can be demolished without further historic review for the next five years.” Still, Levinsky optimistically points out that, as of this writing, no formal demolition permit has been filed. “We are still very hopeful that the work we did over the summer to identify alternatives, explore preservation tools, and bring experienced parties to the table will lead to a win-win outcome for the owner and for the building, which was deemed eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in 2008 and is quite a rare resource in Colorado.”

In any case, Tom’s Diner will shut its doors for good sometime in the near future. The diner—even beyond its architecture—is a special place, among the last of a dying breed of uniquely American spaces.

A warm welcome

I visited Tom’s for the first time last July, a few days into a long road trip. It was 2:30 on a Friday afternoon, deep into the post-lunch lull. The diner was mostly empty, save for a few other customers, two waitresses, and one person manning the grill, visible from where I sat only by the chef’s hat bobbing to and fro. I sat alone in a two-person booth, its butterscotch vinyl seat and yellow formica table top looking as if they were beamed straight into the present from 1973. Overhead, a neon sign buzzed its message toward the street.

My waitress, Jana, was the kind of person whose warmth and humility positively radiated across the room. Before I had finished my sandwich and first cup of coffee, we had exchanged life stories. She waxed on about love, the brutality of politics, and the pleasures and sorrows of lifelong journeys. We had only known each other for five minutes but it was clear we’d both made a new friend.

Jana, 2018. | Photo: Tag Christof Jana, 2019. | Photo: Tag Christof

This kind of serendipitous connection tends to happen often out on the road, and I find that it can be especially facilitated by these liminal places: motel verandas, smoky bars, and diner counters. They are places people inhabit only temporarily; where people look away from their phones and stop to soak in their surroundings, even if just for a minute.

Jana’s earnest, unvarnished kindness took me by surprise because it felt so wildly out of place in an era where almost no place seems safe from pretense or snark. This kind of simple human connection, I realized while sitting in that booth, is truly a fundamental part of what I love most about road trips. Tom’s name might be on the marquee, but Jana and her warm welcome are the true essence of the diner and every other place like it that welcomes locals and travelers alike.

The secret is in the mayonnaise

When I hear about Tom’s imminent demise this summer, I immediately plan a detour to Denver and drive straight to the diner. It is 1 a.m. and I scarf down some soup and saltines. I chat with a friendly 95-year-old former newspaper editor, but there’s no sign of Jana. I arrange to come back in the morning for breakfast and meet her at the same table under the neon sign. We talk about love, politics, journeys, and reminisce about the diner before she starts her afternoon shift.

Sam’s “Silly Philly.” | Photo: Tag Christof Sam, a cook at Tom’s. | Photo: Tag Christof

“People have the most incredible stories about this place,” she says. “They met their wives or husbands here, or they come back after moving away from Denver decades ago and are shocked that it’s the one thing around that’s exactly like they remember it.” She tells me about a waitress named Juniper who worked in the diner for decades, and introduces me to the chef, Sam. I order the “Silly Philly” cheesesteak, which Jana says is her favorite thing on the menu. “The secret is all in the mayonnaise,” Sam says.

Jana leads me to one of the restaurant’s thick stone structural walls (a telltale feature of most Googie architecture) and points out an impressive geode built right into the wall. I don’t notice the hidden crystals at first—I have to really look.

“Do you think anyone would build something like this these days?” Jana asks. “Someone had to find this beautiful rock and place it just right, at eye level, and then leave it there for people to discover. Nobody here even noticed it until I found it. Can you imagine? There’s just such a story in this place.”

Neither Jana, nor most of her coworkers, quite know what they’re going to do once Tom’s shuts its doors for good. Word is, they will be given a one-month notice and then will be on their own. Some are making grand plans, starting businesses, and hustling for jobs, while others just plan to go with the flow. Jana plans to take a long road trip back to the small town in coastal Washington where she grew up, near her family and their gem and mineral business.

Making lemonade

I return at the end of Jana’s shift that evening to say goodbye and have one last look around. An apparel designer, and recent transplant to Denver from Berlin, is sitting at the counter reading Chaucer and eating a sandwich. “I’ve read about the architects behind this place and had wanted to see it for a while,” he says. “It is sort of tacky but also wonderful, you know? It’s just so American in a way that is hard to put into words.”

Two other customers, Anna and Alex, live in the neighborhood. They are Tom’s regulars. “We come here pretty often because you can just hang out, the food is good, and the place just looks cool in that old school way,” Anna says. Alex adds: “It’s sad to hear the place is closing. It’s the end of an era, I guess.”

“It is sort of tacky but also wonderful, you know? It’s just so American in a way that is hard to put into words.”

The best case scenario for Tom’s iconic building is that it is saved by a benevolent, visionary developer who realizes the value in its historic architecture. With a little more grassroots help—and a solid 21st-century restoration—a listing on the National Register of Historic Places isn’t far off. Around the country, there’s precedent: The Phoenicia Diner in the Hudson Valley, the Welcome Diner in Tucson, and King’s Road at the Ace Hotel and Swim Club in Palm Springs have all been saved from demolition—even if some of their unpretentious grit has been lost in the process.

I can only hope that Tom’s Diner fate is similar. But even more importantly, I hope its future includes people like Jana, who not only notice, but point out the crystals in the wall.

I meet Zo, a night waitress, just as Jana is finishing her shift. She struts through the restaurant, making it clear that, for now, she is running the show. Diner staff and patrons know that when life hands you water with a lemon slice and a few packets of sugar, you can always make lemonade.

“Mostly I’m looking forward to the goodbye party at the end,” Zo says. “Some really, really good people work here and we really just need to send this place out right.”

If you go

Tom’s Diner is open 24 hours (for now).