As soon as I see the protest signs proclaiming “Trinity victim!” and “Make peace, not war,” I know I’m in the right place. Here, more than 100 miles south of Albuquerque, New Mexico’s largest city, is the Trinity Site, the location of the world’s first nuclear bomb explosion. It was here that the atomic age dawned at 5:29:45 a.m. Mountain War Time on July 16, 1945. Less than a month later, the same style of bomb was detonated on Nagasaki, Japan, instantly killing more than 80,000 people.

To get here, I traveled the same route that Manhattan Project scientists followed from Los Alamos nearly 75 years ago over the cracked, rabbitbrush-studded landscape. The Trinity Site is understandably remote, wedged between two mountain ranges and the bleached hills of White Sands National Monument, the world’s largest gypsum dune field. For a time, a rumor circulated that it was the bomb blast that had turned the sands to the south pure white.

Ground zero still lies within a working military installation. The White Sands Missile Range is the largest open-air land test range operated by the Department of Defense (DoD). On the first Saturday of April and October each year, the site opens its gates and the public may visit a place that has forever shaped warfare, espionage, and global security. In 1952, the DoD opened the site at the request of area churches, whose members wanted to visit and pray for peace. The site’s notoriety has grown and today, more than 2,000 people come to pray, learn, sate a morbid curiosity, or simply check it off their bucket list.

Radioactive rocks

I fall in line with visitors walking the 0.3-mile-long path toward the ground zero marker, and the atmosphere feels anticipatory. People around me make small talk, but their voices are hushed as though we’re walking through a museum. It feels like we’re on a pilgrimage.

As we near ground zero, I hear Geiger counters clicking as they register radioactive material. Trinitite—also known as atomsite or Alamogordo glass—was formed during the test when the blast swept sand into the mushroom cloud, irradiated it under massive heat and pressure, and dropped it back onto the desert floor. The greenish, glassy rocks are radioactive, but visitors still pick up the stones and run their fingers over the pumice-like surface. The site’s radiation is relatively low—and many places on Earth have natural radiation greater than what has been found near ground zero—but I still feel slightly uneasy.

A lava-rock obelisk marks the detonation site and nearby sits a bomb casing that represents “Fat Man,” the plutonium bomb that was tested at this site and later dropped on Nagasaki. Its presence feels simultaneously historically appropriate and menacing.

The Manhattan Project

In the run-up to the first nuclear explosion, scientists were developing two different types of bombs. Manhattan Project sites in Washington and Tennessee were refining plutonium and uranium, respectively. The site in New Mexico was tasked with making the bomb mechanisms work. The uranium bomb used a fairly simple mechanism, similar to a gun (that bomb was dropped on Hiroshima without testing). The science behind the plutonium bomb, however, was less definitive.

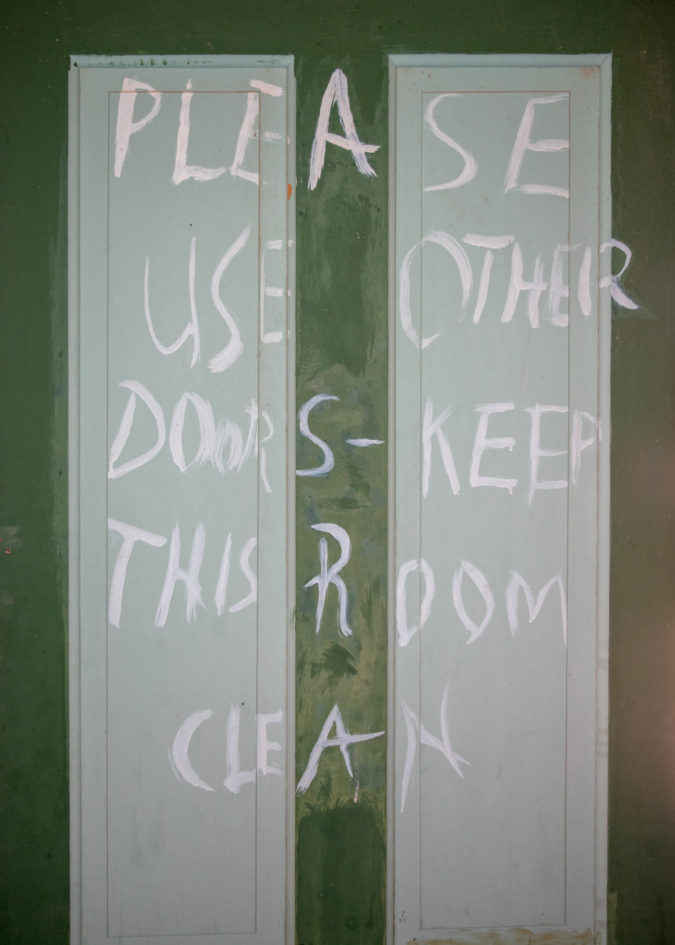

On July 13, 1945, scientists drove three hours from Los Alamos to the range, carrying a plutonium 239 core in a Chrysler Plymouth sedan. Two miles away from ground zero, they assembled the core in a hastily-built clean room in the Schmidt-McDonald Ranch House. They covered the windows with plastic and scientists were told to wipe their feet before entering to keep the desert’s insidious sands out of the careful operation. Once the core and bomb mechanism were assembled, it was suspended from a 100-foot steel tower—one of the concrete footings can still be seen rising from the desert floor near the obelisk.

-

Trinity bomb. | Photo: Ashley M. Biggers -

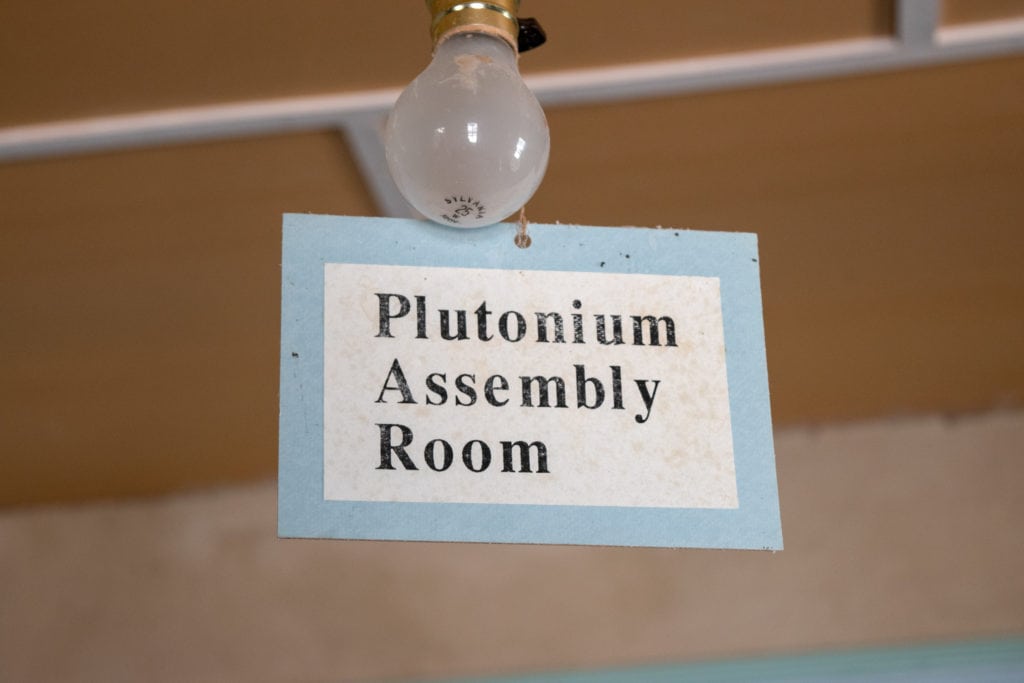

Plutonium assembly room. | Photo: Ashley M. Biggers -

The Schmidt-McDonald Ranch House. | Photo: Ashley M. Biggers

Historic photos along the chain link fence document how the morning of July 16 unfolded. Although scientists hoped to test the bomb, nicknamed “the Gadget,” earlier in the day, rain prevented them from moving forward. They waited for the clouds to clear, huddled in bunkers 10,000 yards away from ground zero (none of the bunkers remain today). Brigadier General Thomas Farrell, chief of field operations for the Manhattan Project, wrote that, upon detonation, “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun.”

New Mexicans reported seeing that near-blinding light some 150 miles away. The shock wave crested across the landscape, breaking windows as far as 120 miles away. The test blew the windows out of the Schmidt-McDonald Ranch House, which has since been restored to look as it did in 1945. The army wasted no time in issuing a cover story claiming that a munitions storage area had accidentally exploded at the Alamogordo Bombing Range. During the blast, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan Project’s head scientist, famously said that a piece of Hindu scripture ran through his mind: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Pain and pride

After the test, two things were certain: The science was solid, and there was no going back.

Although Oppenheimer later claimed that the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings held no weight on his conscience, he said, “In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatements can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

Today, visitors are drawn to the desert from all over the world to see the Trinity Site for various reasons. Vietnam Veteran Hap Chapman of Colorado had been waiting his entire life to visit ground zero. “The millisecond that thing went off, it changed the whole world forever,” he says. “It makes me feel sober—and proud.”

But not everyone views the site with pride. The Trinity Downwinders, a group whose goal is to seek “justice for the unknowing, unwilling, and uncompensated participants of the July 16, 1945 Trinity test in Southern New Mexico,” claim that the Trinity test exposed them to cancer-causing radiation. Although the test site was remote, there were still people living as few as 15 miles away from the detonation site. A Center for Disease Control study found that, “Too much remains undetermined about exposures from the Trinity test to put the event in perspective as a source of public radiation exposure or to defensibly address the extent to which people were harmed.”

I notice a woman standing under a pink parasol. Jo Ann Campmeir came to the Trinity Site from Oklahoma with her husband. As I ask her about her thoughts, tears spring to her eyes and she admits she’s conflicted. “I’ve known people in Japan who survived the bombing and their stories are horrible,” she says. “And I know people like my father-in-law that probably survived [the war] because of the bomb.”

As I walk away, the only sound I hear is that of Geiger counters clicking.

If you go

The Trinity Site is open to the public twice a year, on the first Saturday of April and October. Entrance is free and no reservations are required.