The smell of history is in the very bones of Seattle’s Unity Museum. Any dedicated museumgoer knows the scent: slightly musty, like the smell of old papers and well-worn carpets.

The museum’s main foyer bolsters this image; it’s filled with Victorian furniture, antique player pianos, and shelves lined with books from the last century or earlier. It’s only once I start winding through the rest of the surprisingly spacious rooms that a larger picture begins to unfold. The museum stands as a monument to the past, but it’s also a forum for interacting with the present—and a series of speculations on what might still be to come.

Seattle has a knack for nurturing small spaces that intertwine the artistic and the communal. The Unity Museum, located in the city’s University District, is no exception. Its founders, Peter and Zabine Van Ness, have imbued the space with their personal histories and predilections. Peter passed away in 2020, but Zabine continues to run the museum, offering up a steady stream of intriguing artifacts and ideas.

They opened the museum in 2014, but Zabine had been thinking about social change in the city since she moved here in 1965—and even long before she ever visited Seattle. Growing up in post-war Germany and later traveling to 65 countries, Zabine says she “really felt that this world is but one country, and mankind its citizens.”

The idea behind the Unity Museum is to present history and foster discussions to start looking toward solutions for tomorrow: “Learn from yesterday, plan for today, so we’re ready for the future.” Yet it almost feels disingenuous to call it a “museum”—because while it undoubtedly fills that role, it goes far beyond the standard concept of what one might find in such a space.

A gateway to innovation

If you aren’t looking for the entrance, you might miss it. An open door leads to a narrow, tall flight of stairs, guiding visitors toward a mysterious space beyond. Zabine resides in the main foyer, ready at a moment’s notice to give a tour. Around the corner, an extensive library sits open, filled with stacks of science books, ethnographies, and political magazines, all of which are available for visitors to peruse.

Walk a little further, and you may come across a group of college kids studying, or activists plotting their next collective action. Tea and coffee are readily available, and a large TV plays a variety of programs, often nature documentaries. Interspersed throughout are the museum’s exhibits, large and small, layered on and around each other, inviting visitors to draw unusual connections.

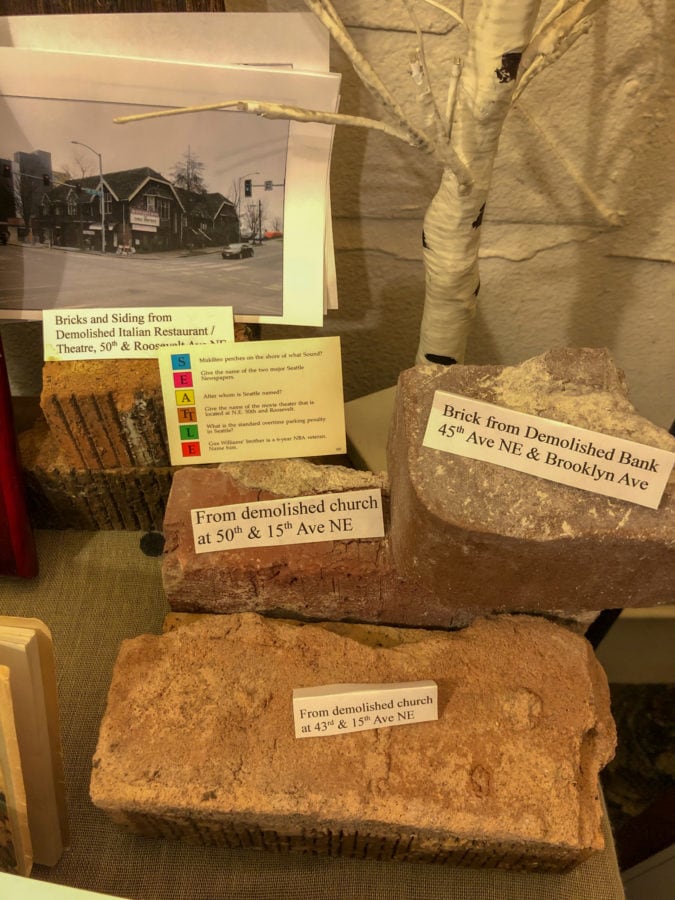

Although the museum showcases a variety of rotating historical exhibits—including ones on women’s history and past pandemics—its primary collections celebrate the city of Seattle, and the University District in particular. Due to its proximity to the University of Washington, the area has hosted scores of intellectuals, artists, and pioneers throughout the years. Zoning maps and bricks rescued from demolished local restaurants offer poignant signs of a neighborhood rapidly growing and transforming, even as many fight for historic preservation. “Seattle has been a gateway to innovation for a very long time,” Zabine says.

“Seattle has been a gateway to innovation for a very long time”

The meditation room, which holds texts and artifacts from a number of religions around the world, is about connecting to what Zabine calls the “unknown essence,” exploring the broader reaches of the soul and the universe. It’s one of the many thematic threads running through the space, all tied in some way to the broader realm of communication.

Zabine is a member of the Baha’i faith, which promotes religious equality and global harmony. These ideals are particularly reflected in this room, where each spiritual text is given equal priority, and the overall atmosphere is that of contemplation. As always, the deeply complex, utterly human process of interpersonal connection is front and center.

These goals are also reflected in the communal aspect of the museum. While some guests only stop by once, many become repeat visitors, and the space is as much a social forum as it is a cultural one. There are several regular volunteers present, including Cameron Cook, who helped set up many of the technological experiences. For him, “it has to do with being part of the community,” he says, helping to guide visitors through their individual experiences. “They’re always here longer than they thought [they would be].”

A growing idea

Zabine is brimming with predictions for the decades to come, including co-ops in space, intricate virtual reality worlds, and 3D-printed homes and foods. Indeed, the museum’s engagement with its physical community is complemented by a robust and growing online presence. There’s already a virtual Unity Museum featured in the communal online platform Decentraland. In this realm, the museum is able to present galleries with a more global focus, and experiment with expanded programs such as online classrooms and empathy-building games.

“We’re really a growing idea,” Zabine says. “We’re about vision, and not about square footage.”

At times, the constant interplay of past, present, and future can feel overwhelming, but after a loop or two through the exhibits, and a few conversations, it all starts to coalesce into something cohesive. It may be the product of the Van Nesses’ unique minds and passions, but the museum is also geared toward broader shared experiences, and Zabine hopes guests feel inspired to reflect on their unique position in geography and history.

The History Train

The last room in the building is the most intricate. Although there are more infographics and historical artifacts around the edges, they are eclipsed by what’s at the center: a massive diorama, with the grandiose goal of showcasing the last several centuries of human progress. And circling it all is a tiny, steadfast model locomotive, known as the History Train.

The diorama is a sprawling collection of pet projects and bits of analysis; sensory overload but with a beautiful order to it all. After chugging past the invention of the telegraph, a World’s Fair, various wars and struggles for civil rights, and the creation of the computer, the train passes by models of the possible futures perpetually being discussed in neighboring rooms. Then it travels through a tunnel made up of beautiful, multicolored arches, awash in neon, and glides straight back to the earliest era, the future and the past forever connecting to each other.

In some ways, the vision of tomorrow that the museum propagates is so abstract, so far-reaching, that it feels like a fantasy. And yet, there is a beauty in that; for, as the slow but steady circuit of the History Train shows, sometimes those abstract, seemingly-impossible concepts really do become reality.

“Ideas start in small places,” Zabine says. “But they end up in innovative spaces.”

If you go

The Unity Museum is open on Tuesday, Wednesday, Saturday, and Sunday from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m.