Three loud whaps, then silence. No humans witnessed the grisly scene, but the next morning, Ritchie Doyle found three dead mice in traps he’d set the night before.

Doyle spent a lot of time at a train depot-turned-playhouse in Virginia City, Montana, putting on the Gold Rush Medicine Show with fellow actor, playwright, and former Virginia City mayor, Allyson Adams.

“He was a poet, songwriter, banjo player, and actor,” Adams says of Doyle. “He loved people and loved telling stories.”

But in the summer of 1998, Doyle had decided mice weren’t welcome in the playhouse. When Doyle found the dead mice, however, Adams says he was traumatized and felt compelled to honor the mice with a proper burial at Boot Hill Cemetery.

“He had a tender soul,” Adams says.

So who were these mice and what did they do to deserve such a swift end? According to their hand painted grave markers, “Sneaky Mouse” was captured and killed for loitering and stealing cheese. “Sqeeky Mouse” was captured and killed for leaving messes and crawling up ladies’ dresses. And “Cheeky Mouse” was captured and killed for moving into cabins, vagrancy, and tearing up books.

Alder Gulch

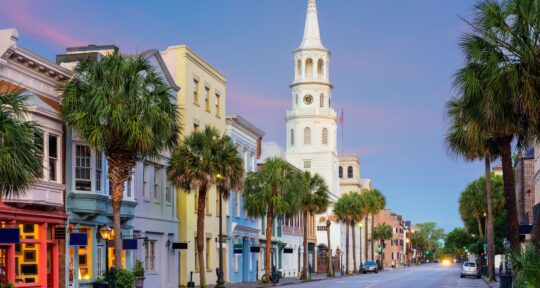

Each summer, 500,000 tourists visit Virginia City, a National Historic Landmark in southwest Montana surrounded by mountain peaks topping 10,000 feet. My mom and I are two of those tourists as we’re taking one of many “one last time” road trips so she can see where her ancestors settled during the gold rush.

In 1863, my great-great-great grandfather, Dr. Don Byam, hoped to trade in his stethoscope for a pickaxe. He never found gold, but he staked a claim and built a home and doctor’s office in Nevada City, just up the road from Virginia City, that still stands.

Despite living a century apart, Dr. Byam and Doyle had something in common—both wanted to rid the area of varmints. When prospectors in nearby Alder Gulch struck gold, robbers began holding up stagecoaches carrying gold to the territorial capital in Bannack. Today, Alder Gulch is home to restaurants, hotels, cabins, vaudeville performances, and activities that include stepping back in time at Virginia City’s storefront museums and Nevada City’s Living Museum.

But in the late 1800s, Montana was not yet a state and no territorial judicial system existed. With the U.S. embroiled in a civil war, sending law enforcement to the newly-formed Montana Territory was a low priority for President Lincoln. Residents hired Henry Plummer as sheriff and set up their own legal system, a so-called miners’ court.

On December 18, 1863, the miners’ court named Dr. Byam and Judge Wilson as judges in a case against George Ives, who was accused of murder. After a three-day trial, jurors convicted Ives. Hours later, 1,500 spectators gathered to see him swing from the hastily built gallows.

Montana Vigilantes

Crime seemed organized with insider knowledge about when gold was being moved from Alder Gulch to Bannack. Concerned citizens met two days after Ives’ trial to take the law into their own hands, calling themselves the Montana Vigilantes. Their numbers grew quickly in Bannack, Virginia City, and Nevada City. They met often in my great-great-great grandfather’s home.

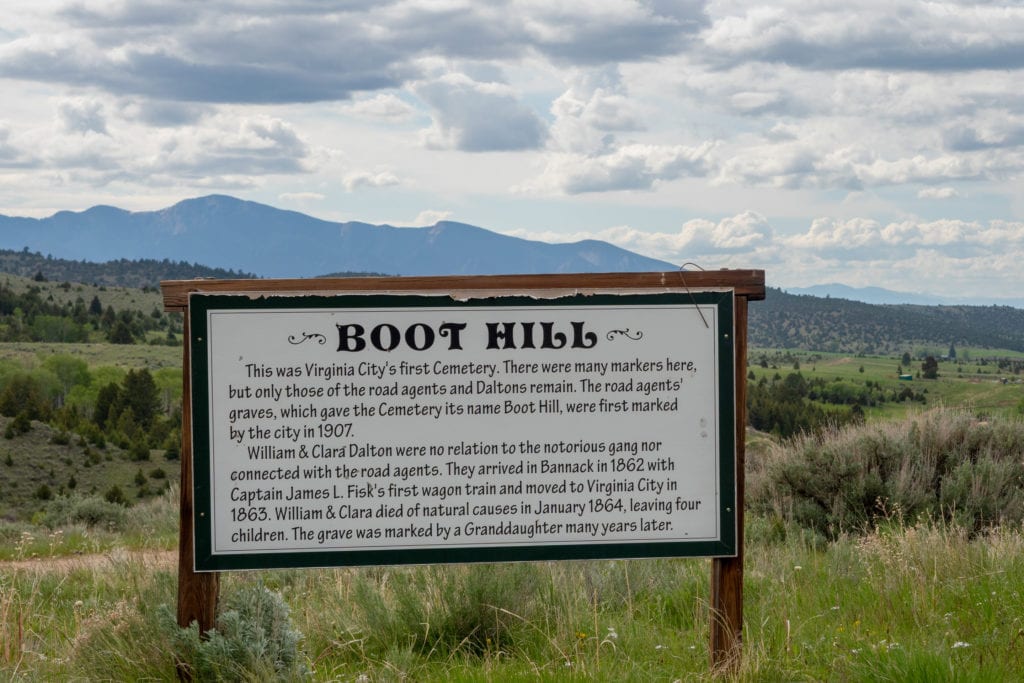

The Vigilantes suspected Sheriff Plummer and his two deputies were leaders of the 100-man strong road agent gang blamed for violent holdups and up to 100 deaths on the road between Virginia City and Bannack. In January 1864, Vigilantes nabbed and hanged Plummer and his associates. But the lawlessness continued. In February, the Vigilantes found “Clubfoot” George Lane and four more road agents guilty of robbery and murder. All were hanged simultaneously in Virginia City and buried on Boot Hill—so named because they died with their boots on.

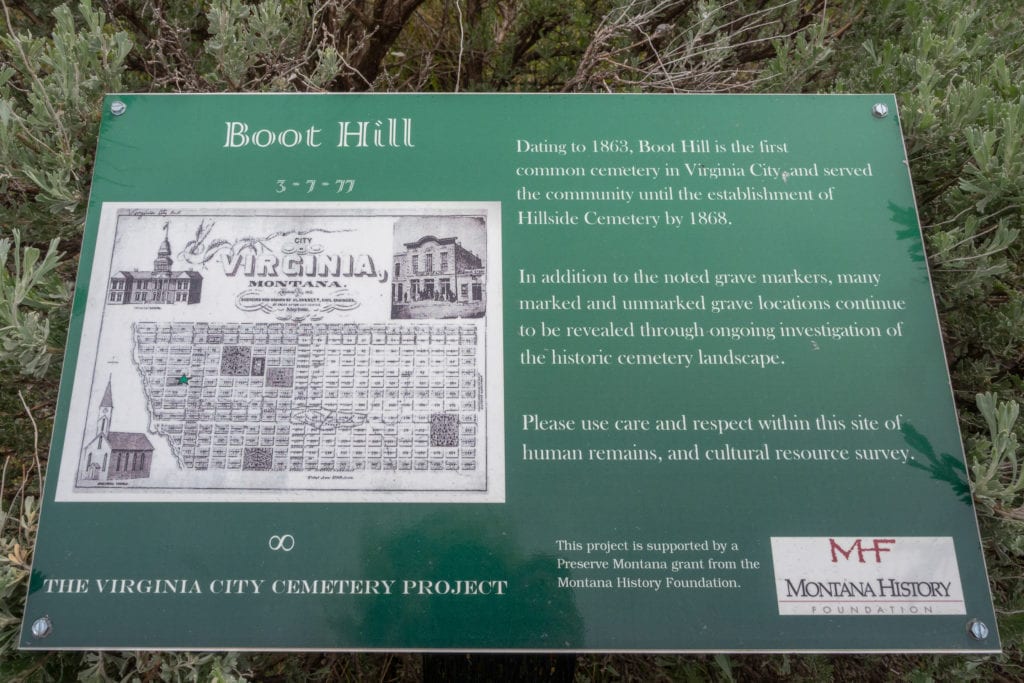

Over the next three years, Vigilantes would leave a calling card with suspected gang members—either a sign with skull and crossbones or the numbers 3-7-77. No one knows for sure the meaning of the numbers, but some historians have suggested they refer to a grave’s dimensions: 3 feet wide, 7 feet long, and 77 inches deep. Today, if you happen to be stopped by the Montana Highway Patrol, you’ll see a patch embroidered with “3-7-77” on the officer’s uniform.

By 1867, the Vigilantes had become bullies. Amid allegations of funneling information to the road agent gang, townspeople forced the Vigilantes to disband. All told, the Vigilantes hanged 24 men, most of which were buried on Boot Hill—all but five in unmarked graves.

Boot Hill

In 1907, Virginia City Mayor James G. Walker, together with several friends and a bottle of whiskey, set off to find the men’s graves. When their shovels hit a casket containing the remains of a man with a deformed foot, they knew they’d found “Clubfoot” George. They marked his grave along with the graves of Jack Gallagher, Boone Helm, Hayes Lyon, and Frank Parish. Their tombstones still stand today.

When we drive up a gravel road to Virginia City’s Hilltop Cemetery to check on our dead relatives, we take a detour to Boot Hill to see the road agents’ simple, hand painted tombstones. From the hilltop, snowy Sphinx Mountain looms to the southeast and I have a bird’s eye view of Virginia City’s Opera House, train depot, and historic Fairweather Inn.

I’ve admired the view here before, inhaled the sagebrush-scented breeze, and listened to the grasshoppers. But today, I notice the other graves on Boot Hill. No grand sign points to them, just a weathered cross flanked by three white tombstones, standing no more than six inches high—commemorating the three mice who paid the ultimate price for trespassing in the playhouse more than 20 years ago.

After Doyle gave the mice a proper burial, he drifted away from summers in Virginia City and passed away in 2018. Angela Mueller, one of the 150 year-round area residents, tends the rodent graves these days, repainting the tombstones every year or so. When I ask her about the names and crimes, Mueller smiles. “I may have come up with one or two of the names,” she says.

If you go

Virginia City and Nevada City sit along Highway 287 in Montana. Virginia City is 90 miles from the entrance to Yellowstone National Park via West Yellowstone. To reach Boot Hill, turn north off Highway 287 (Wallace Street) onto Hamilton Street and head uphill turning left at the fork in the road near the hillcrest.