Who would you like to meet at a dinner party and why?

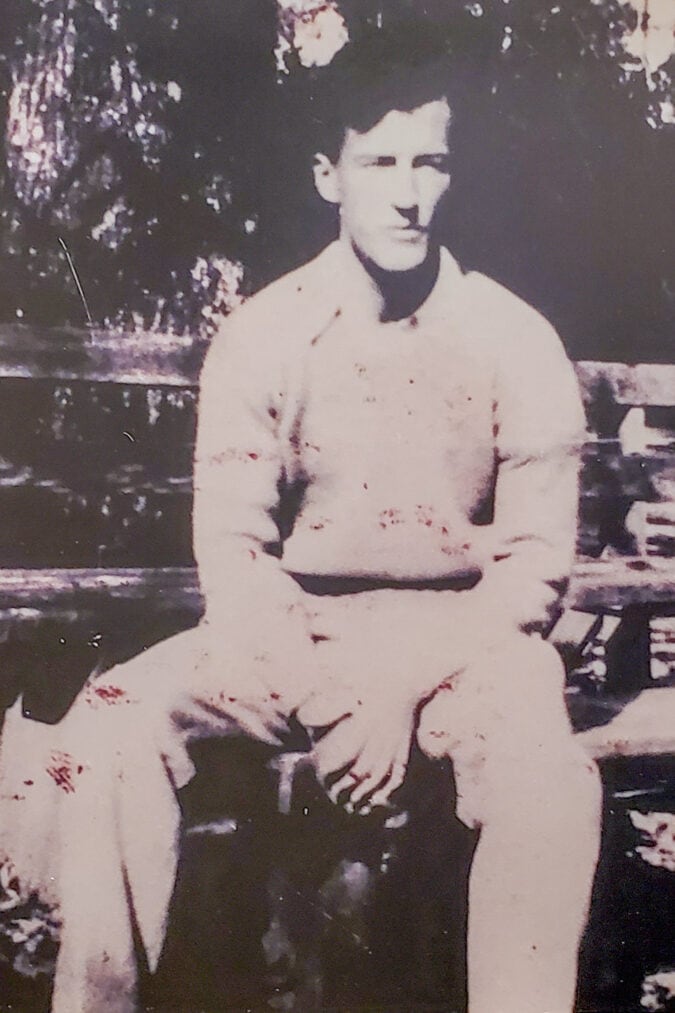

If I could turn back time to early 1965, I’d like to meet Louisiana-born artist Walter Anderson. From an outsider’s perspective, Walter’s life was full of challenges, heartbreak, and rejection. But his artwork proves he was also resilient and capable of creating art that transcended his earthly problems while delivering an astonishingly beautiful glimpse into the natural world he experienced.

The Walter Anderson Museum of Art, located in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2021. The museum is a testament to Walter’s keen eye for the natural beauty he wished to share. Walter’s son, John, a psychologist, and Anthony DiFatta, an artist and the museum’s educator, share their insight into the artist’s unconventional life as I take a tour.

“If you confuse abnormality with insanity, then a sane man in an insane world looks crazy,” John says. “With [my dad], there are so many misconceptions.”

A Hitchcock cameo

Maybe Walter was just born at the wrong time. Today, he might be admired for his eco-friendly lifestyle and love of nature. Walter preferred the solitude of Mississippi’s Horn Island, where he spent time drawing, painting, and taking shelter under his skiff for weeks at a time, to his more conventional life on the mainland. He was an enigma to his wife, Sissy, and their four children. On shore, Walter often lived apart from his family.

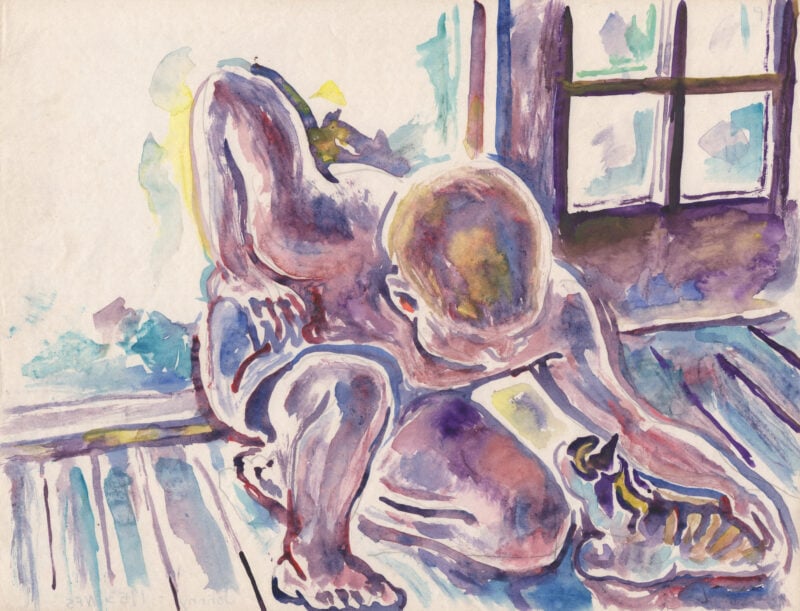

As a kid, John says he and his siblings were embarrassed by their father, who preferred pedaling a bicycle to driving a car—even when traveling across the country. Walter worried little about wearing a rumpled fedora or mismatched shoes. He felt lucky to find a matching pair. After Walter died, John found his father’s painting of him as a boy petting the family’s cat, O’Malley.

“I had no idea he had painted it,” John says. “I was a dour, serious little boy, nobody’s favorite playmate, but I loved that cat and she loved me. I thought I kept it a secret but when I found this painting, I realized that my dad had seen it, had known it, had understood it. He chose to depict me not as a dour cynical curmudgeon but as a loving little boy.”

John continues, “He knew me much better than I really thought, and he loved me very much. That’s what [the painting] triggers in me when I look at it so it will always be my favorite.”

Walter was a prolific artist. His eponymous museum displays everything from the artwork he did to relearn drawing after aggressive psychiatric treatment, to pottery he designed and decorated for his family’s business, Shearwater Pottery. He painted on reclaimed wood and reams of typing paper. He stamped and painted block prints on the back of wallpaper rolls, selling them for a dollar per foot. By his own admission, his need to create art was like a physical craving, a compulsion. Once completed, Walter often used his crumpled typing paper drawings as a fire starter.

But he didn’t harbor resentment toward the Ocean Springs residents who didn’t understand his way of life. When no one answered his invitation to participate, Walter worked alone for 16 months on a 3,000-square-foot mural in the town’s community center, which now adjoins the museum. The painting depicts the area’s history—and the artist himself, shown rowing a boat.

“His self-portrait is like a Hitchcock cameo,” John says.

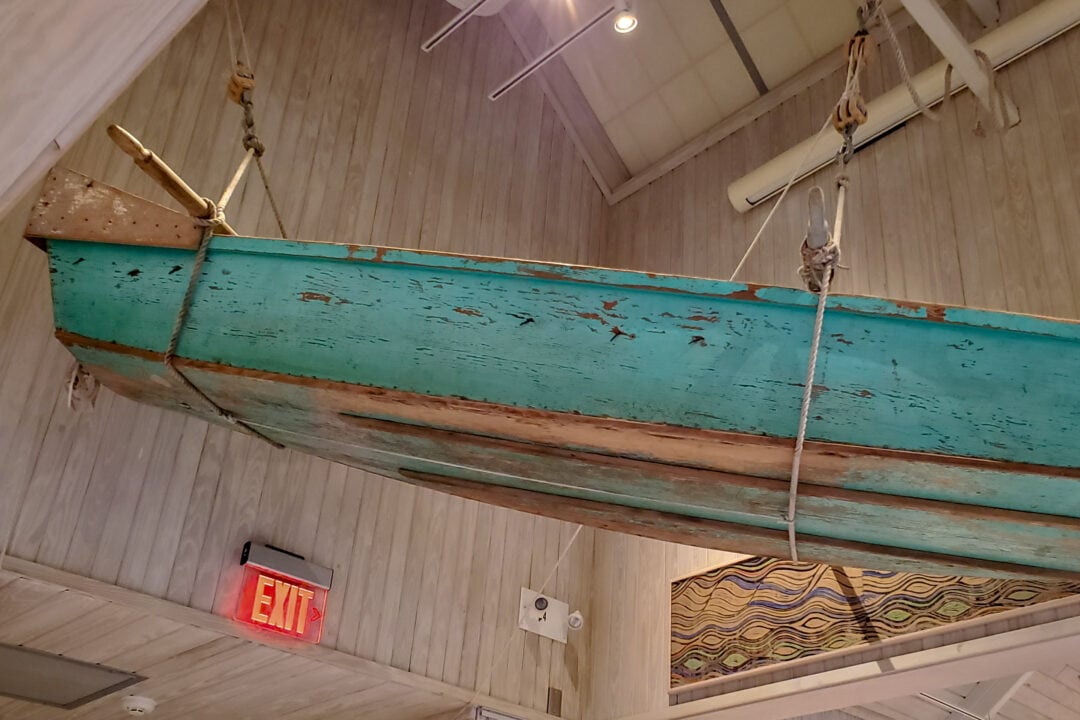

Horn Island

It took Walter, and his loaded skiff, a day or two to reach his campsite on Horn Island, 12 miles off the Mississippi coast. The skiff now hangs in the museum, and a photograph shows a barefoot Walter in his boat, surrounded by the Gulf of Mexico, using a bedsheet as a sail.

“He was pretty much a complete outcast throughout his life,” John says. “I believe my dad went out to Horn Island because it was easier to love people with a little bit of separation, without any conflict, without friction. It gave him a place from which he could love without reservation.”

Once on the island, he often stayed for a couple of weeks. He sketched and drew what he saw, what he ate, and what he experienced. Walter “looked from nature rather than at nature,” John says. “It was impossible for him to spend any time without nature.”

Walter began to reflect on his love of the natural world even more after he was hospitalized for mental illness. He took comfort in the company of Split Ear, a rabbit, and a sow that visited his campsite. Wildlife was a frequent subject in his art and journals.

When a cottonmouth bit him, he wrote, “A nest caught my eye. It was too high for me to see into it, and I did something I never do, I reached up to feel into it, thinking about eggs or baby birds. I was pierced immediately as with the sharp point of a knife. It was a dreadful shock. Out of the nest came a startled moccasin. We looked at each other as if to say, ‘How could you do this to me?’ He let me go away, I let him go. It was as if there were no recriminations, just recognition of mutual fault.”

A secret masterpiece

Back on shore, Walter continued to work on a masterpiece in his small studio, unbeknownst to his family. John and Anthony wonder if he painted scenes from Horn Island to keep nature close when he was away from his beloved island.

When Walter passed away in 1965, Sissy and her sister unlocked the studio. “When my mother and aunt Pat opened the room, Pat said, ‘Creation at Sunrise!’” John says, “It was Eden.” Walter left a handwritten copy of Psalm 104, a creation hymn, on a chest that was full of paintings—a surprise to his wife, who believed her husband to be more of a beachcomber than an artist. Eden, now located in the museum, affects everyone differently. John says people often laugh or are moved to tears in the room. Anthony says he visits the painting to recharge whenever he can.

As I gaze upon each wall, seeing an alligator, a squirrel, and butterflies, I’m transfixed by the room’s glow. How did Walter so perfectly recreate what he called the magic hour, the time when nature is bathed in golden light just before sunset? It would be the first question I’d ask him at my dinner party.

If you go

The Walter Walter Museum of Art is open Monday through Saturday 11 a.m to 5 p.m. and Sunday from 1 to 5 p.m.