On one of the busiest street corners in Jersey City, New Jersey—surrounded by bars and auto body shops—sits a tiny diner serving even tinier hamburgers. The red, white, and chrome White Mana Diner, a rare surviving (and thriving) relic from the 1939 New York World’s Fair, manages to look both retro and futuristic at the same time.

Marketed at the fair as “The Diner of the Future,” the White Mana was also billed as an introduction to the concept of “fast food.” The innovative little diner has a round, central counter to encourage efficiency: Without taking more than three steps in any direction, an employee can reach the grill, soda station, cash register, and customer.

Mana (or manna) is a term used in the Bible to refer to God’s nourishment. Before regular health inspections, business owners would paint their establishments white to convey cleanliness to their customers. Within a 25-minute drive from the White Mana, diners can still visit the similarly-named White Rose Diner and a White Castle outpost.

But it’s not enough to simply declare that your diner is clean by adding white to the name—all those white surfaces require constant vigilance. Mario Costa, the current owner, started working at the White Mana in 1972. He says he wasn’t on the job more than a few minutes before his boss—original owner Louis Bridges—handed him a rag.

“He told me to start wiping, and I never stopped,” says Costa.

Sliders and steak sandwiches

The White Mana has a full menu—including steak sandwiches, hot dogs, and breakfast—but it’s the burgers that attract diners at all hours of the day and night. The White Mana is open 24 hours a day and only closed three days a year: Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve. Friday and Saturday nights are so busy that burgers are served as take-out only.

“Sometimes the diner is so crowded we have no place to keep the buns,” Costa says, a fact he attributes partly to its location on Tonnelle Avenue. Also known as U.S. Route 9, it was once referred to as the state’s “liveliest highway.”

Costa gives me a thorough explanation of why the tiny burgers that White Mana serves by the bagful are called sliders. “People think it’s because they’re little and when you eat them they just slide right down,” Costa says. “But that’s not true.”

-

The burgers are called sliders because they are slid from one side of the grill to the other while they cook. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The cheeseburger special includes three sliders, fries, and a soda. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

The grill has three sections: a left burner, a middle section without a burner, and a right burner. The tiny patties of red meat, seasoned and smashed flat with onions, begin cooking on the left side. When they are almost cooked through, the burgers are moved to the middle, topped with buns, and kept warm until a customer arrives. The cook then slides the burgers one last time, and they finish cooking on the right burner. The cheese is added and the burgers are (paper) plated with a side of pickles.

The cheeseburger special is the most popular order; it includes three cheeseburgers, fries, and a soda. The burgers are small but mighty—I had three in one afternoon and wasn’t hungry again until the morning. Although the burgers are no longer 15 cents, for less than $10 I guarantee that you won’t walk away from the White Mana hungry.

World of Tomorrow

Six months before the start of World War II—on April 30, 1939—the second-most expensive World’s Fair of all time opened in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens, New York. Over two years, more than 44 million visitors came to the fair to catch a glimpse of “The World of Tomorrow,” including exhibits introducing nylon, color photographs, air conditioning, the fax machine, and early televisions.

When the fair closed, Bridges bought the experimental diner. He had it moved from Queens to New Jersey, where it reopened in 1946. He eventually opened four other White Man(n)a locations, but the one in Hackensack is the only other surviving one. The two diners are no longer affiliated with each other, and in fact, there’s even a bit of friendly competition between the locations.

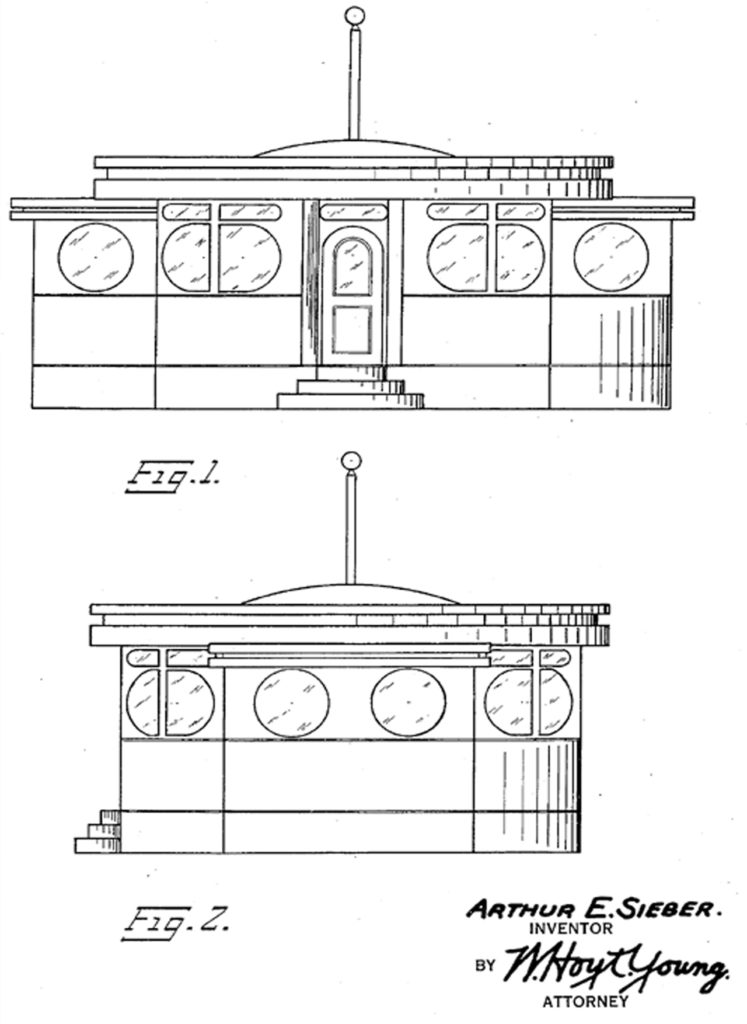

On an episode of Food Feuds, the Hackensack location was determined to have a better slider—but Costa disagrees and even accuses the White Manna’s owner of riding on the historic coattails of his original diner. Although photos of the White Mana at the fair are elusive—if they exist at all—it’s hard to dispute an original architectural rendering of the diner, dated 1938.

The diner was built in two sections and if you look closely, you can still spot the seams. Costa didn’t have to pay taxes on the “moveable” diner until he built the brick addition in the 1980s to accommodate larger groups and families with children, making it a permanent structure.

“Instead of becoming a lawyer, I became a burger guy.”

After Louis Bridges died in a car accident, ownership of the diner transferred to his brother, Webster. Webster Bridges—memorialized today by the Mana’s quarter-pounder, the Big Web—didn’t share his brother’s enthusiasm for the tiny diner. In the 1970s, thinking the White Mana had been rendered obsolete by chains like Burger King, he began to seriously consider selling the diner.

In 1979, Costa, who had been working at the diner to save money for law school, used the money to buy the diner instead. “I’m glad I stayed here,” Costa says. “Instead of becoming a lawyer, I became a burger guy.”

-

The White Mana is proud of its World’s Fair heritage. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The White Mana’s most popular seller is the slider. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The brick addition was added to accommodate larger groups and families with children. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Something special

Costa isn’t the only employee with no plans to leave the White Mana. Rigo Lopez has been working behind the counter for 19 years. “The diner is something special,” he says. “I love it because you meet a lot of nice people and we have a great view; you can see everything.”

Lopez, who is also a talented photographer, points out the elaborate, tiled floor. “This is the original floor,” he says. “Laid one piece at a time—it almost looks 3D.”

A lot of the White Mana is original—including the counter and stools—which makes it even more of a treasure in an era when diners are disappearing at a disturbing rate. Costa actually sold the diner in the late ‘90s, but quickly regretted the decision when he heard that the new owners wanted to demolish the historic structure and build a Dunkin’ Donuts. He bought it back, paying much more than he had sold it for, and in 1997, the Jersey City Historic Preservation Committee declared the diner a local landmark.

-

There are several booths and stools in the addition. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

A lot of the fixtures are original to the diner, including the counter and stools. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The diner was built in the round so an employee never had to walk more than three steps to serve a customer seated at the counter. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The hand-tiled floor is also original to the diner. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

The windows no longer open, but the view is nice. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan

”I’d rather pay them, like somebody pays a fighter to step aside,” Costa told the New York Times. ”(Mike) Tyson did that with Lennox Lewis so he could fight Bruce Seldon. $4 million, Tyson paid. I’m looking at it like I got to pay these people to step aside.”

One thing that isn’t original to the diner is the name—patrons of the diner at the fair (and other locations) might have noticed that the Jersey City location is missing an “n” from “Manna.” Privilege signs—popular from the 1930s through the 1960s—were given to owners for free and maintained by the parent company, in exchange for the advertising they provided. Sometime in the ‘80s, Costa sent his sign to the Coca-Cola Company for a refresh. When it came back missing a letter, Costa just kept it that way.

Patrons and pigeons

Costa, who lives nearby, also owns The Ringside Lounge and boxing gym across the street. Its unassuming location attracts heavyweights like Mike Tyson, who, at the height of his popularity, used to train at Costa’s gym, unbeknownst to paparazzi.

Costa has always been interested in boxing, and he and Tyson became fast friends. On the roof of a building that Costa also owns, across from the diner, sits one of Tyson’s beloved pigeon coops. Tyson stops by whenever he’s in town, and they frequently participate in—and win—prestigious pigeon races.

Famous patrons of the diner include the rapper Akon, Snoop Dogg, Dustin Hoffman, Chuck Berry, and Arturo Gatti, another boxer. Other regulars aren’t considered national celebrities, but Costa still treats them as such.

Billy Clark has been coming to the White Mana since 1949, when he was 12 years old. Costa doesn’t hesitate to dial Clark on his cell phone when he forgets the name of a regular and Clark quickly recalls it. Sal Cuccio was the only patron—that they know of—that had been to the White Mana in both its original location at the fair and in its current location in New Jersey.

“[Cuccio’s] mom packed a lunch for him and he put it in a locker at the fair,” Costa says. “It was June so maybe it was hot, but for whatever reason the lunch was no good and he had to eat, so he ended up at the White Mana.”

Costa might look every bit the part of New Jersey wise guy, but inside he’s as soft as his signature sliders. He lets local children use his gym for free after school to keep them out of trouble, and sponsors Little League teams. “This has been my life since I was a kid,” he says, gesturing around the diner with an unlit cigar in hand (he gave up smoking six months ago, but finds it helpful to keep his hands occupied).

“The diner is like a Broadway show—but better,” Costa says. “Because the characters are real people. You have the real firefighter, the real policeman, everyday, ordinary people—they’re the real deal. I like feeding them and making them happy.”

If you go

The White Mana Diner is located on the corner of Tonnelle and Manhattan Avenues in Jersey City, New Jersey. It is open 24 hours a day, closed only on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Eve.