In its early days, Cheyenne, Wyoming was savage. It was a ruthless, lawless town—a real-life Hell on Wheels—at the crossroads of the brand new Union Pacific Railroad.

With all the violence, gambling, and hard drinking, Cheyenne was no place for a lady. But women on the Plains were different from New England society gals and Southern debutantes. In a town that should have chewed them up and spit them out, Cheyenne’s women instead grew tough skins and loud voices.

By 1869, before suffragettes had begun marching on the East Coast, Wyoming women had won the right to vote. Before most U.S. states had granted women the ability to own property, Wyoming women were homesteading and ranching. The infamous Calamity Jane, an occasional resident of Cheyenne, allegedly quipped, “A girl with a husband can be limited in what she can do, a girl with a rifle ain’t got that problem.”

Cheyenne’s women took to ranching culture with fervor. They broke wild broncos, roped steers, and branded calves. Most could ride a horse before they could walk. In that regard, Wyoming hasn’t changed much. Just ask Lisa Murphy.

Miss Rodeo Wyoming

My first introduction to Murphy is at the Cowgirls of the West Museum in downtown Cheyenne. She’s not there when I visit but her red leather chaps with silver fringe are, along with a red-and-black horse collar embroidered with the words “Miss Rodeo Wyoming.” In a promo photo, a fresh-faced, bright-eyed young woman tips her white cowboy hat to the lens of the camera.

“My grandfather taught me to ride horses when I learned to walk,” Murphy tells me later. “I was a junior barrel racer, a dandy for Cheyenne Frontier Days, and then I competed for Miss Rodeo Wyoming.” For the title, Murphy had to excel at skills including horsemanship, speech and interviews, and congeniality. Winning, she says, was the opportunity of a lifetime.

That was 1988. Thirty years later, when we meet in person at Cheyenne Frontier Days (CFD), a rodeo, carnival, music festival, and parade all rolled into a 10-day event, Murphy is just as lovely and just as badass, wearing the blue plaid button-up, jeans, and cowboy boots that identify the event’s more than 2500 volunteers. Created 123 years ago as a one-day cattle roundup and cowboy competition testing essential ranching skills, CFD has blossomed into the country’s largest outdoor rodeo—aptly nicknamed the “Daddy of ‘em all.”

For the women of Cheyenne, this year’s Frontier Days is extra special; it coincides with the 150th anniversary of Wyoming women’s right to vote. Murphy, the first woman to serve as chair of the festival’s board in 2017, is the perfect behind-the-scenes guide at the arena. We walk through rows of pens, each containing muscular horses with shining coats and massive bulls lounging in the sun. Below the stadium seating at the arena, competitors in cowboy hats tape up their elbows and ankles in a metal-fenced, outdoor green room. Injuries are par for the course in rodeo sports; more than one cowboy offers us a tale of lacerated internal organs.

This year the CFD has added a new women’s event: breakaway roping. It’s a heart-pounding, high-speed horseback chase to rope a running calf (the rope breaks apart quickly after the calf has been lassoed). The competitors must not only be skilled horsewomen and ropers but absolutely fearless; even this relatively non-contact sport can get a rider thrown from her horse at 55 miles per hour without a helmet.

If the rodeo is Cheyenne Frontier Days’ most adrenaline-fueled event, the Grand Parade is its most folksy. This procession—which includes highschool drill teams, military units, state officials on horseback, and hundreds of other Cheyenne-ites in carriages and vintage cars—happens not just once, but four times during the 10-day celebration.

-

A bull rider at the rodeo. | Photo: Shoshi Parks -

Wyoming governor Mark Gordon in the Grand Parade. | Photo: Shoshi Parks -

Bulls resting before the CFD rodeo. | Photo: Shoshi Parks -

Competitors mingle and prep in the waiting room behind the arena. | Photo: Shoshi Parks -

Horses run through the rodeo arena during the CFD opening ceremonies. | Photo: Shoshi Parks

By the time I arrive the morning of the first parade, it seems everyone in town is already here, either participating or watching from the sidelines. Even Wyoming’s governor, Mark Gordon, rides by on a handsome, prancing buckskin horse with a lasso coiled at his side. There’s something about the hominess and heritage of this event that moves me to tears.

Suffragette city

The suffragettes appear midway through the procession: women in white shirts, long black skirts, and purple-and-yellow-edged ribbon sashes. They carry homemade signs with phrases such as “150 years of women’s suffrage in Wyoming.” To say that Wyoming was the first state to grant women the right to vote is a bit misleading since it was still a territory in 1869. In fact, it was the transition to statehood two decades later that was the true test of Wyoming’s suffrage.

For Wyoming to join the Union, Congress demanded that the territory rescind women’s right to vote. Local lawmakers were on the fence and, as they debated the path forward, one woman, heavily pregnant and dressed in 22 pounds of corsets and fabric, went to work. Theresa Jenkins hitched up her horse and buggy and went door-to-door urging women to assemble and demand their rights. If the U.S. wouldn’t accept the rights of Wyoming’s women then, by golly, they’d stay a territory. By the end of the day, hundreds of ladies had gathered at the Capitol Building, their heavy, frilly dresses filling the downtown area with color. It’s rumored that Jenkins’ voice was so powerful that women four blocks away could hear her call to action.

-

Downtown Cheyenne. | Photo: Shoshi Parks -

A mural in downtown Cheyenne. | Photo: Shoshi Parks -

Cheyenne Capitol Building. | Photo: Shoshi Parks

The plan worked, at least in part, says Pope. “The legislature was a little leery to change their vote when they had all those women out front carrying on.” Wyoming upheld the voting rights of its women and was still accepted into the Union, becoming the first state where eligible women could fully participate in the democratic process (Native Americans and Chinese immigrants were still not allowed to vote). Her objective achieved, Jenkins returned home that afternoon and went into labor, giving birth to a daughter she named Agnes.

Winning, and keeping, the right to vote wasn’t the only political first attributed to the women of Cheyenne, and Wyoming as a whole. The first woman to serve as a justice of the peace in the U.S., Esther Hobart Morris—a “tough old broad” nearly six feet tall, according to Pope—sat on the bench for nine months in South Pass City in 1870. One of the first things she did? Have her husband arrested as drunk and disorderly.

Then there was Estelle Reel, the first woman elected to federal office in 1894 as the superintendent of public instruction. Nellie Tayloe Ross became the first female governor in the U.S. after winning a special election in 1925, following the death of her husband, then-governor William. The following decade Ross broke through yet another glass ceiling: securing an appointment as the first female director of the U.S. Mint.

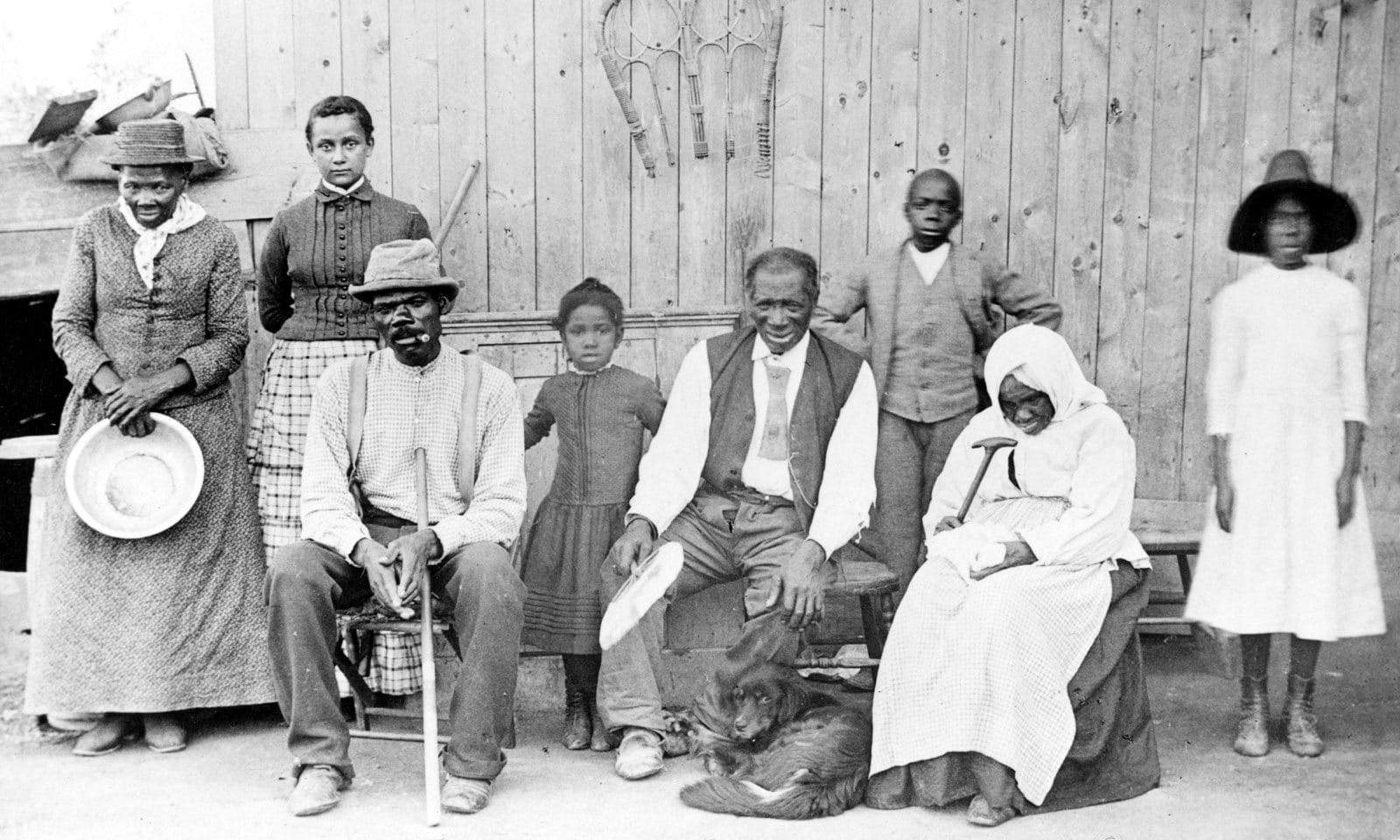

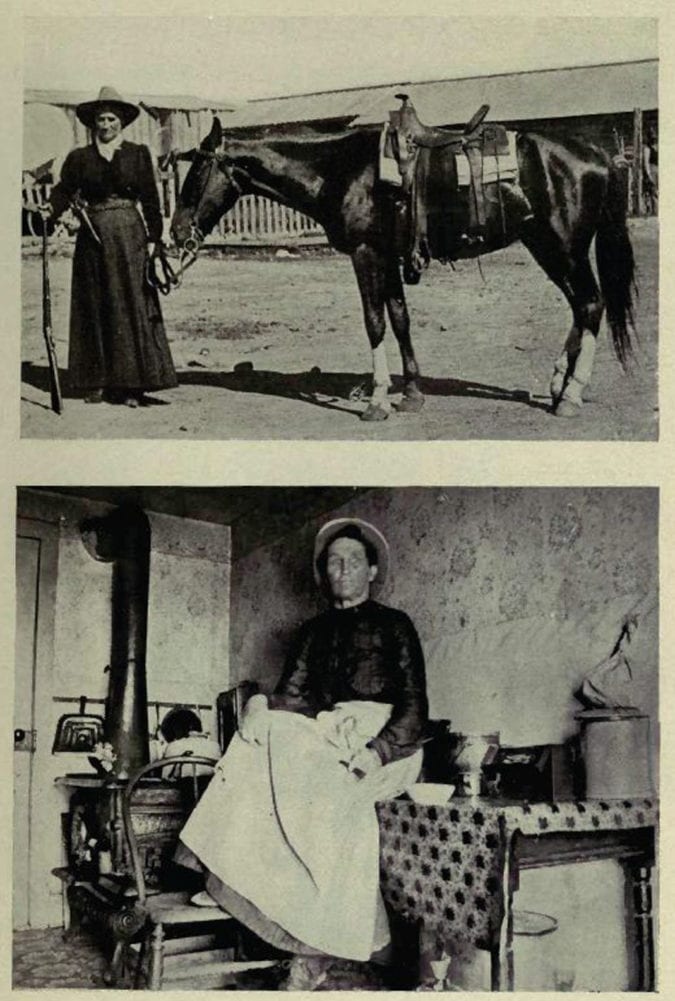

The toughest woman in the land

For every Cheyenne woman who made the history books, there were hundreds of others whose feat was simply to survive in harsh prairielands where men outnumbered women six to one and violence was a way of life. “The women of the West were strong stuff. When you think about coming out here in wagons, and all these crazy characters with guns. I mean, they couldn’t keep all the ruffians under control,” says Pope. And among those ruffians: Miss Calamity Jane, the roughest, toughest woman in the land.

There are so many legends about Calamity Jane that it’s hard to parse fact from fiction. What we do know is that she dressed as a man, worked as a military scout on the frontier, played sidekick to folk hero Wild Bill Hickok, and told stories in the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

A notorious alcoholic, Jane was well-known in Cheyenne’s saloons. “Women weren’t really allowed in the bar but she’d go in all the time, belly right up with the guys,” Pope says. “She’d shoot up the mirror backs behind the bar, and they just loved it.” Stumbling out drunk late at night, Jane had a habit of stealing whatever horse was standing around. One time she stole a horse and buggy and made it all the way to Fort Laramie, around 100 miles away from Cheyenne, before being stopped by authorities.

For better or worse, Cheyenne’s bar scene is a bit quieter today than in Calamity Jane’s day. On Friday night at the 26,000-square-foot Outlaw Saloon, couples two-step beneath laser lights and patrons throw back shots of whiskey and bottles of beer. In 2019, there’s only one way for a gal to show her mettle here—the mechanical bull. Whether it’s Calamity Jane on my shoulder or the Bud Light in my glass, it’s a challenge I eagerly accept.

I saunter up to the bull operator, pay ten dollars, and wobble across the bouncy house floor to the headless creature. Throwing my leg over its soft hide, I scramble into the saddle and adjust my skirt, a poor clothing choice for this rodeo adventure. I last exactly 22 seconds before toppling off, cowboy boots in the air, laughing loudly.

“Not too bad for my first time,” I decide as I gracelessly stumble to my feet and curtsey to the hooting, hollering witnesses. I know if Calamity Jane were here, she’d be laughing, too.

If you go

The Cheyenne Frontier Days—the “world’s largest outdoor rodeo and Western celebration”—take place every year in July.