Retired from 40-plus years as a public-school educator, I decided to become a trout bum. I bought a 13-foot Scamp trailer, loaded it with fly rods, and hit the road. On my first trip, I spent 2 months fishing my way west from Ohio through Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, and Montana. After traveling more than 3,500 miles west, and fishing in 18 rivers and streams, it was time to head home. Heading east from Dillon, Montana, I stopped in Virginia City for lunch.

I didn’t know that Virginia City is a ghost town transformed into a large open-air museum. In the 1850s, the town was the territorial capital, filled with 25,000 citizens drawn by the discovery of gold and silver. It had Montana’s first newspaper; Mark Twain wrote for it when he was in town. When the gold and silver were gone, the town emptied out. By 1871 there were only 200 residents left, including Sarah Bickford.

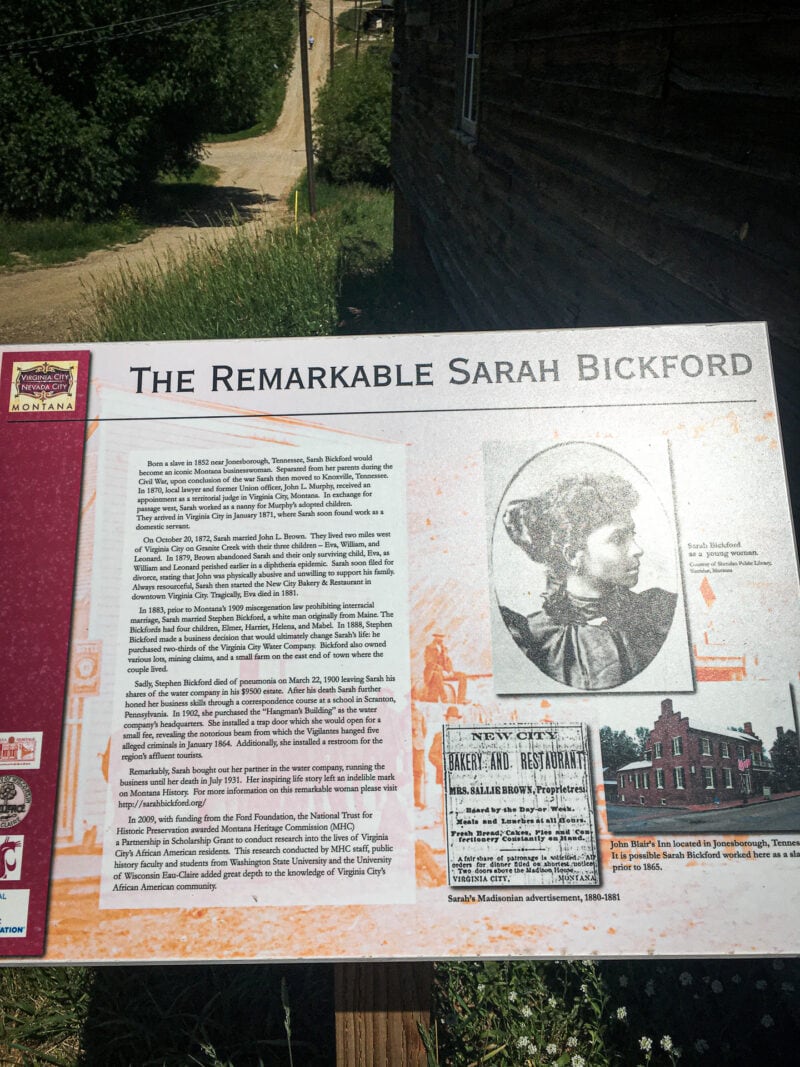

I learned about Bickford from the Remarkable Sarah Bickford Marker. Born into slavery around 1852 and freed after the Civil War, she made her way to Virginia City in 1871. In 1883 she married white miner and farmer Stephen Bickford—26 years before Montana would outlaw interracial marriage. Stephen died in 1890, leaving Sarah with four children and two-thirds of ownership in the Virginia City Waterworks. She took business classes by correspondence, and, in 1903, purchased the remaining third of the utility, becoming the first and only woman in Montana—and probably the nation’s first Black woman—to own a utility company.

Before I read about Bickford, I had no intention of stopping at small-town museums on my road trip. I was a museum snob, willing to travel to Los Angeles or New York to see well-known collections, yet unwilling to drive a few miles to see what people in small towns value enough to preserve. It was learning about Bickford’s remarkable life that made me rethink my biases. On the way home, I stopped every chance I had to visit these local treasure chests.

Open the flood gates

Outside the city of Huntley, Montana, I found the Huntley Project Museum, which documents one of the first major water projects in the U.S. The Reclamation Act of 1902 funded ditches to divert water from the Yellowstone River for homesteaders. In 1907, the first flood gates were opened. While the drought of 1910 drove most of the settlers off, some remained and many of their families still farm in the region.

The museum is a 10-acre park with reconstructed farm homes, barns, stores, outhouses, and antique farm equipment. A ditching machine sat rusting in the sunshine as if waiting for its operators to return. The tar paper homesteaders’ shack, a 10-by-12-foot room, held my attention the longest. Barely big enough to hold the stove, bed, table, and chairs the settler had amassed, I could not imagine surviving the elements in it. Summer temperatures on the Montana plains easily top 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and in the winter, drop well below zero.

Winds that roar unimpeded by hills or trees often tore the tar paper to shreds or simply toppled the small structures over. Entire families lived inside, families that had been dropped off beside a rail line with little more than the clothes on their backs, some rolls of tar paper, and enough dried goods to last them a few months. I will never again complain about the size of the shower in my Scamp.

Further to the east, a sign advertising “Steer Montana, World’s Largest Steer” lured me to the O’Fallon Historical Museum in Baker, Montana. The museum consists of six separate buildings, including the former county sheriff’s office where Steer Montana resides. The beast weighed 3,980 pounds, stood 5 feet, 1 inch tall, and was 10 feet, 4 inches long. His size is attributed to the whisky mash he was fed, a by-product of his owner’s moonshine still. He has his own room in the old sheriff’s office.

After paying my respects to Steer Montana, I wandered around the buildings stuffed with what local people felt was worth holding on to. There were cars from the past nine decades, the projector from the last drive-in movie theater in the county, buggies, carriages, and folk art by local artists. A one-room schoolhouse held old maps, books, and desks.

Of all the displays, I studied the cork bulletin board in a side room covered with black-and-white photos of young people from Fallon County the longest. The photos were accompanied by articles that celebrated their enlistment or deployment to fight in WWII. Their hats sat at cocky angles on their heads, their smiles told you they didn’t have a care in the world. Most of them didn’t come home in one piece.

In Regent, North Dakota, I found the Hettinger County Historical Society Museum. It occupies most of the main street, in seven buildings that formerly held businesses. There’s a reconstructed church, a one-room schoolhouse, and the main street with boardwalks where, if you had been here 100 years ago, you could mail a letter, get a haircut, and buy your groceries. There’s also Dr. Hill’s office, complete with instruments, pill bottles, and a soda fountain.

At Potosi, Wisconsin, I found the Potosi Brewery and National Brewery Museum, rated by Forbes as one of the five best beer museums in the world. The brewery building was in disrepair after closing in 1972 but was saved by locals who wanted to restore the building. Once you’ve restored a brewery building it’s only a small step to again brewing beer, which began in 2008. The museum, stuffed with signs, bottles, cans, glassware, and more, reminds the visitor that at one time there were thousands of small breweries dotting the country. Run by a non-profit foundation with all profits going to local charities, the brewery, museum, and restaurant is the area’s largest employer, drawing more than 70,000 visitors annually. The beer is pretty good too—I bought a case to support the charity.

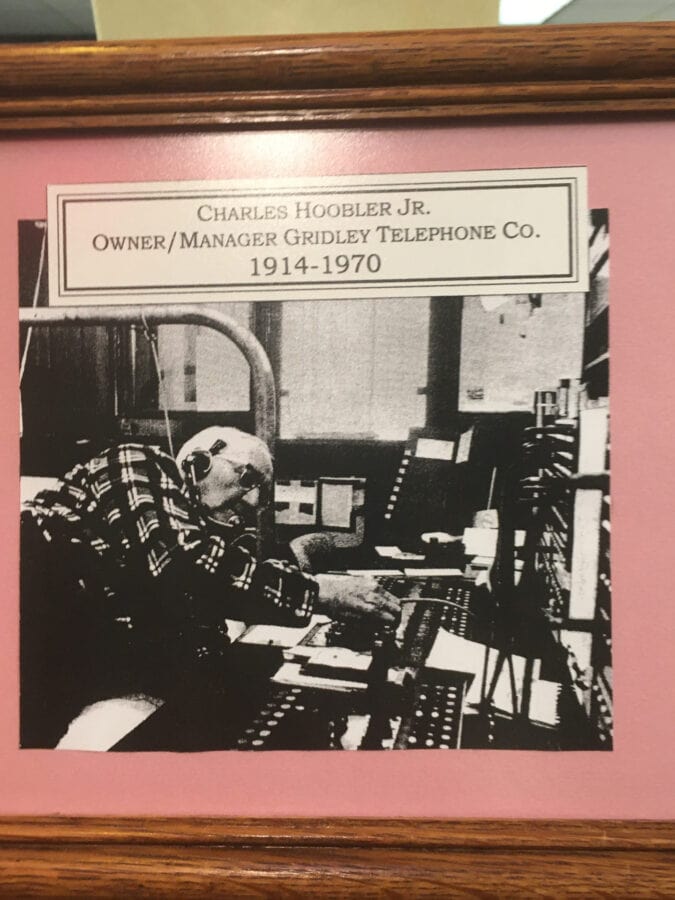

The last stop on my way home was the Gridley Telephone Museum in Gridley, Illinois. It features a collection of rare antique phones as well as the independent phone service’s switchboard, all utilized until 1971. Docents told me stories of children calling switchboard operators and simply asking for their grandmother, or patients seeking the doctor being told he was just seen walking to the diner for lunch. When the switchboard was replaced, Gridley became the first phone service in the U.S. to exclusively use touch-tone phones since dial phones had never been installed. The system went from the most ancient technology to the most modern overnight.

I’m planning this year’s trout bum tour to the Northeastern states, my desk covered with maps and fishing reports. There’s also a folder labeled “America’s Attics” slowly filling with side trips to the small-town museums that I will always seek out when I hit the road.