As I step inside the grandiose lobby of The American Club in Kohler, Wisconsin, I have a difficult time picturing this five-star, five-diamond resort as a dormitory for single, immigrant men. But the Club once housed up to 300 workers at a time—all of whom came to the U.S. from various European countries to work at the Kohler Company across the street.

The son of an immigrant himself, and a staunch proponent of workers’ rights, Walter J. Kohler opened the doors of The American Club to his factory employees in 1918. The initiative was fueled by his personal understanding of the tribulations immigrants face when coming to the U.S. Walter’s father, John Michael Kohler, emigrated with his family to Wisconsin from Austria as a 10-year-old boy. After attending college in Chicago and going to work as a salesman, John purchased an iron and steel foundry from his father-in-law during a major recession. He built it into a successful bath and home manufacturing company; Kohler Co.’s first bathtub was created in 1883. Today, a statue of a 10-year-old John stands at the resort’s entrance.

Throughout my visit to this stately, brick-clad campus, the inspiring story of Kohler Co. transports me back in time more than 100 years. Thanks to the careful and thoughtful preservation of its unique immigrant history, The American Club stands today as a living embodiment of the American Dream.

A sense of camaraderie

Not all the men who worked at Kohler Co. were single. Many came to the U.S. to work, saving their earnings with the hope that their families could eventually join them. “I think it’s just incredible that the original intent of the building is still true today—to provide this really gracious experience to single men of modest means that weren’t usually given that opportunity to establish themselves,” says Angela Miller, associate manager of archives and heritage communications for Kohler Co.

The men were provided with three meals a day—including a 90-minute lunch break—and had access to a barbershop, laundry service, bowling alley, and tavern. Each resident paid $27.50 a month, just enough for the club to break even and cover its operating costs. “The goal of the building was to be able to provide hygiene, nutrition, and recreation [for the men]—all things that Kohler considered basic needs,” Miller says.

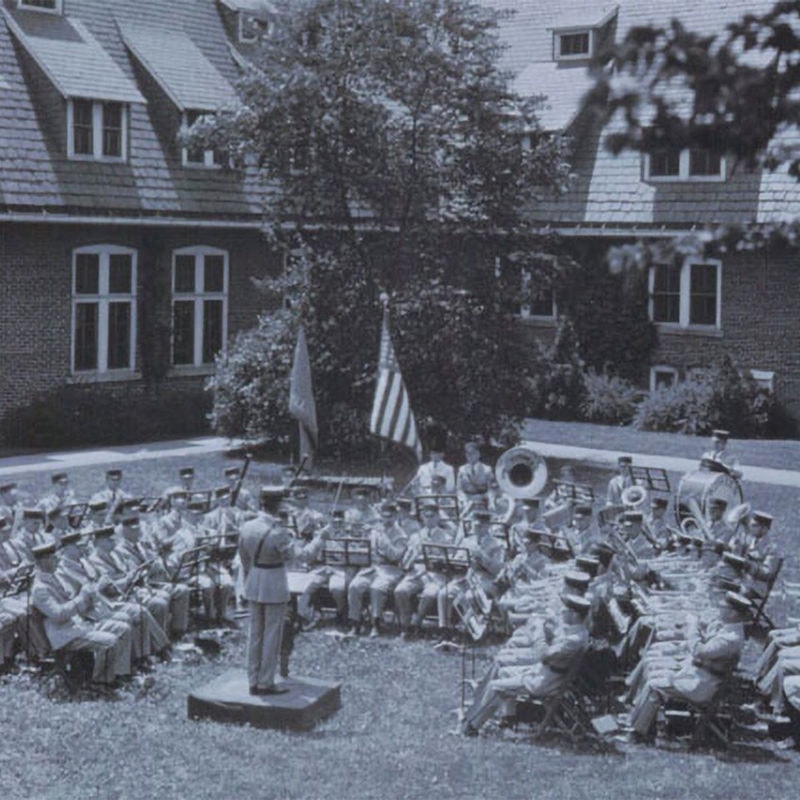

Kohler—who served as Governor of Wisconsin between 1929 and 1931—also established a sense of camaraderie and community among the workers, who would play cards together and compete in baseball leagues, attend concerts, raise cattle, and harvest their own food from nearby gardens and farms. But his most impactful contribution was encouraging and helping his workers become American citizens.

Kohler provided classes in English and American history, and those who demonstrated an eagerness to learn were given opportunities to be promoted within the company. April 7 was established as “Americanization Day” and each year, workers who wished to file their “first papers” for citizenship would be given a paid day off and transportation to the courthouse to do so. By 1930, the Kohler Co. newspaper reported that nearly 700 immigrants had taken out their first papers since the Club’s establishment.

Preserving history

When the housing was no longer necessary and the Club was reopened as a resort in 1981—with five championship golf courses—it was important to Kohler that its history not be erased. The American Club is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and today, glimpses into its past life are scattered throughout the resort’s many rooms. In the library, original blueprints, artifacts, and images are on display and a tiny bar operates out of what was once the barbershop.

The former dining hall, where the workers gathered for meals below two massive American flags, is now called the Wisconsin Room. In place of the flags in the formal, farm-to-table restaurant hang two large tapestries that depict Wisconsin’s ethnic history. A pair of unmissable quotes serve to remind diners of the resort’s founding principles and Kohler’s personal mantras: “Life without labor is guilt” and “He who toils here hath set his mark.”

“It’s something Walter really believed in—that the people working really hard in the factory deserved more than just a place to work and a wage,” Miller says.

As I walk toward Horse & Plow, the resort’s casual pub, I pass through the Hall of Immigrants, which includes collections of old photos, newspaper articles, and citizenship papers. Inside the workers’ former tavern, where card matches and billiards were played, the tabletops are constructed from the former bowling alley.

In the lower level of The American Club, where the laundry facilities and bowling alley once resided, sits The Immigrant Restaurant. Aptly named, it features a series of six small dining rooms, each uniquely designed to pay homage to a different country whose people settled in Wisconsin and lived at the club. A true patriot, Kohler “wanted to make sure they were giving a nod to the people that the building was originally built for,” Miller says. “He believed that workers deserved roses as well as wages—that the company owed it to them to see they were building a life for themselves.”