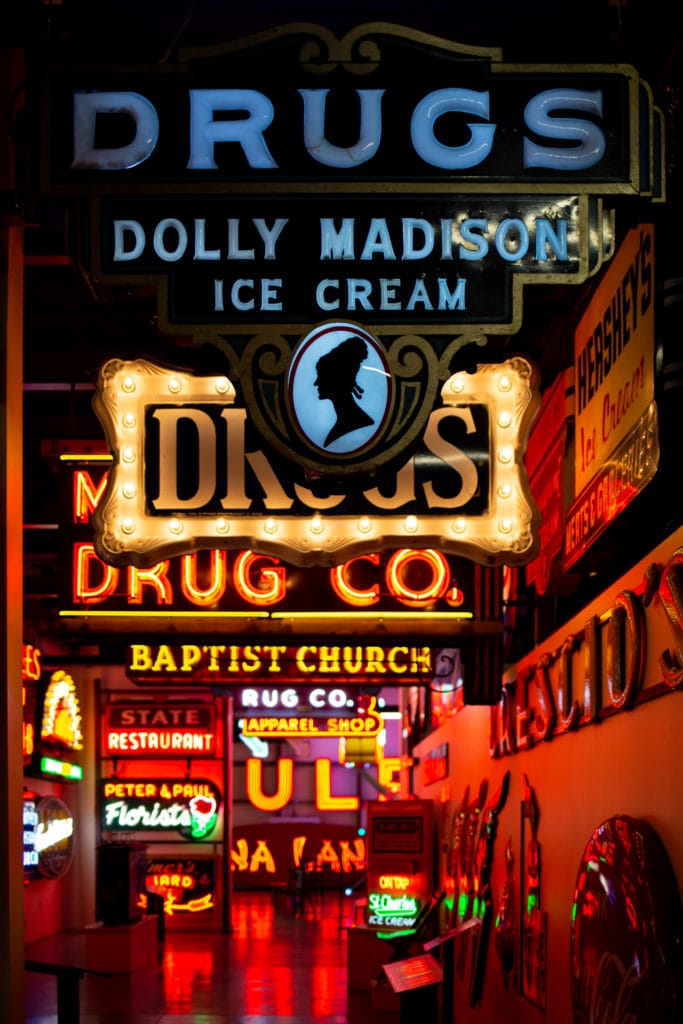

How do you pick just one sign to advertise a museum “dedicated to the art and history of commercial signs and sign making?” If you’re the American Sign Museum in Cincinnati, Ohio, you don’t—the parking lot belonging to the nearly 20,000-square-foot museum has no less than ten signs.

A few of these signs utilize neon, some are painted on the side of the brick building, and others—such as a large pig—are a nod to the trade sign era, when a cobbler would advertise his business to (often illiterate) customers with a sign shaped like a shoe.

At the American Sign Museum, signs are not just a precursor to the main event, they are the star attraction. Owner Tod Swormstedt spent 26 years working as the editor of Signs of the Times, a trade magazine for sign fabricators, founded in 1906. Swormstedt describes himself as a collector of many things, not just signs: “I’m not a hoarder,” he insists. “I’m a collector.”

A hobby becomes a museum

In 1999, Swormstedt created the National Signs of the Times Museum—later renamed the American Sign Museum—to “not only save signs, but to show appreciation for the craftsmanship that goes into making every sign,” he says. Other neon-centric sign museums have opened since, but the American Sign Museum claims to be the only museum dedicated to the art and craft of sign-making. The collection not only includes the signs themselves, but also books, catalogs, tools, blueprints, equipment and other ephemera related to the history and process of sign-making.

Swormstedt, who has lived in Cincinnati for most of his life, searched all over the country for the perfect home for his collection. He considered opening his museum in Las Vegas, Chicago, New York, Memphis, and St. Louis before deciding on southern Ohio. “I had to go all over the country looking for a home and ended up right back where I started,” he says.

In 2005, Swormstedt finally found a warehouse that provided both the high ceilings and industrial backdrop befitting his collection. Built in the early 1900s, the building was home to Fashion Frocks, a Cincinnati business that enlisted housewives to sell women’s clothing door-to-door. During WWII, the factory switched to manufacturing parachutes. Now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the building had previously sat abandoned and badly neglected for many years before it was purchased and refurbished by Swormstedt.

As any collector will tell you, there is never enough space, and Swormstedt is currently in the process of expanding the museum. The $3.5-million project will add 20,000 square feet of exhibit space in the next few years, including sign painting and metal shops, and space for artists-in-residence and temporary exhibitions.

A hundred years of history

Although the neon signs are quite literally the flashiest pieces in Swormstedt’s collection, the museum comprises signs from more than 100 years of sign history. The pieces are organized more or less chronologically, so visitors can follow the evolution from object signs of the trade era through to the introduction of light bulbs, neon, plastic molded signs, and beyond.

Hand-carved wooden signs from the pre-electric era of the late 1890s feature gold leaf lettering that still sparkles, proving that you don’t need electricity to capture a customer’s attention. But it’s the pre-neon light bulb era that is Swormstedt’s favorite, because of the craftsmanship involved. “It’s not that I don’t like neon,” he’s quick to clarify. “It’s just that in the light bulb era they did so much with so little technology.”

Signs not only advertise their respective businesses, but now serve as historical objects, representing the times in which they were created. The museum is home to an iconic Big Boy statue, whose red hair, 3D slingshot, red-and-white striped overalls, saddle shoes, and chubby cheeks date him to the early ‘60s.

Future iterations of the Big Boy removed the slingshot, thinned out his physique, and simplified his wardrobe. The burger hasn’t changed much through the years, but the sauce does vary by region: Tartar sauce in the Midwest is replaced by mayonnaise in the California version.

Swormstedt used his connections in the sign industry to acquire a lot of the pieces in his collection, and about half of the signs have been donated. “Family businesses squeezed out by Walmart who want to preserve the legacy and history of their signs come to me and say, ‘Hey Tod, do you want this?’” he says.

As sign-collecting has grown in popularity—and as the monetary value of vintage signs has increased—Swormstedt’s reputation has been an asset. “Companies know I’m not going to sell their signs on eBay or to American Pickers,” he says.

Tubes and transformers

Neon signs in the collection are repaired by Neonworks, the only neon fabrication and repair shop located within a hundred miles of the museum. Neonworks, started in 1991 by Tom Wartman and Greg Pond, rents space from Swormstedt; visitors are encouraged to tour their workshop and witness a neon tube-bending demonstration.

Neon, discovered in 1898, is an odorless and colorless inert gas found naturally in the atmosphere. When vacuum-sealed in a glass tube with electrodes affixed on each end, neon glows reddish-orange. Tubes filled with argon gas (mixed with a bit of mercury) glow blue, and additional colors are achieved by either painting the outside of the glass or by coating the inside of the tube with fluorescent powder. Neon sign-making technology hasn’t changed much over the years, although tubes containing mercury are no longer repaired but rather replaced entirely.

Tom Wartman, who learned the trade from his father, is working on a sign for a local beauty salon when I visit. He heats up the skinny glass tube and bends it effortlessly into the shape of an R—a process that surely looks much easier than it actually is—blowing into the tube occasionally to relieve stress from the bent glass.

When asked if he’s noticed a resurgence in the popularity of neon, Tom Wartman shrugs. Being a tube bender is “like being a musician,” he says, laughing. “I don’t recommend it.”

Ashley Wartman, Tom’s niece, worked in the corporate world for 18 years before finally joining Neonworks eight months ago as a sign technician. She assembles signs, runs diagnostics, repairs broken signs from the museum’s collection, and has aspirations to learn the art of tube bending from her uncle.

Sheltered from the elements, glass tubes and transformers can last for decades, although occasionally “guests will bump into a sign and break a tube,” Ashley Wartman says. Neonworks doesn’t do on-site repairs for outside businesses and due to the fragile nature of their work, they have a “no ship” policy—a fact that she was reluctant to share with the actor Tim Robbins when he visited recently and inquired about a custom sign.

Awkward celebrity encounters aside, “you gotta love working here,” Ashley Wartman says. “It’s unique and creative, and the environment is comfortable and fun, relaxed. This is the place I want to be every day. Neon signs have always been a part of my family. I know the business, it just made me happy. I want to be a tube bender and that’s what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

When asked to pick a favorite sign from his collection, Swormstedt declines. “I’m like a little kid at Christmas—the first present he opens is his favorite,” he says. “Every new sign is my favorite one—until the next new one.”

Every new sign is my favorite one—until the next new one.

—Tod Swormstedt, founder of the American Sign Museum

He does admit to favoring the “funkier” signs, including a spinning, Sputnick-inspired Satellite Shopland sign and a rotating globe from Earl Scheib, an auto body and paint shop in Compton, California. Ironically, the Scheib sign—from a company famous for declaring that they would “paint any car, any color, only $29.95”—is one of only five in the collection that has been repainted.

The sign also came with a bullet hole, which Swormstedt chose not to repair. “The stories behind the signs are what make them interesting to me,” Swormstedt says. “The amount of money that a sign is worth isn’t what makes it valuable to me—it’s the history.”

If you go

The American Sign Museum is open Wednesday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.; Sundays, 12 p.m. to 4 p.m. Entrance is $15 for adults and $10 for seniors (65+), students, and military. Three children (12 and under) are free with each paid admission.