The moment I push through the heavy doors at the front entrance, I’m met with the sweet relief of air conditioning after braving Pittsburgh’s record-breaking July heat. I take in the massive vestibule walls, covered from floor to ceiling with a repeating pattern of hot pink cows on a bright yellow background. Quickly ducking around two girls posing for a picture, I know that I’m in for a completely unique experience.

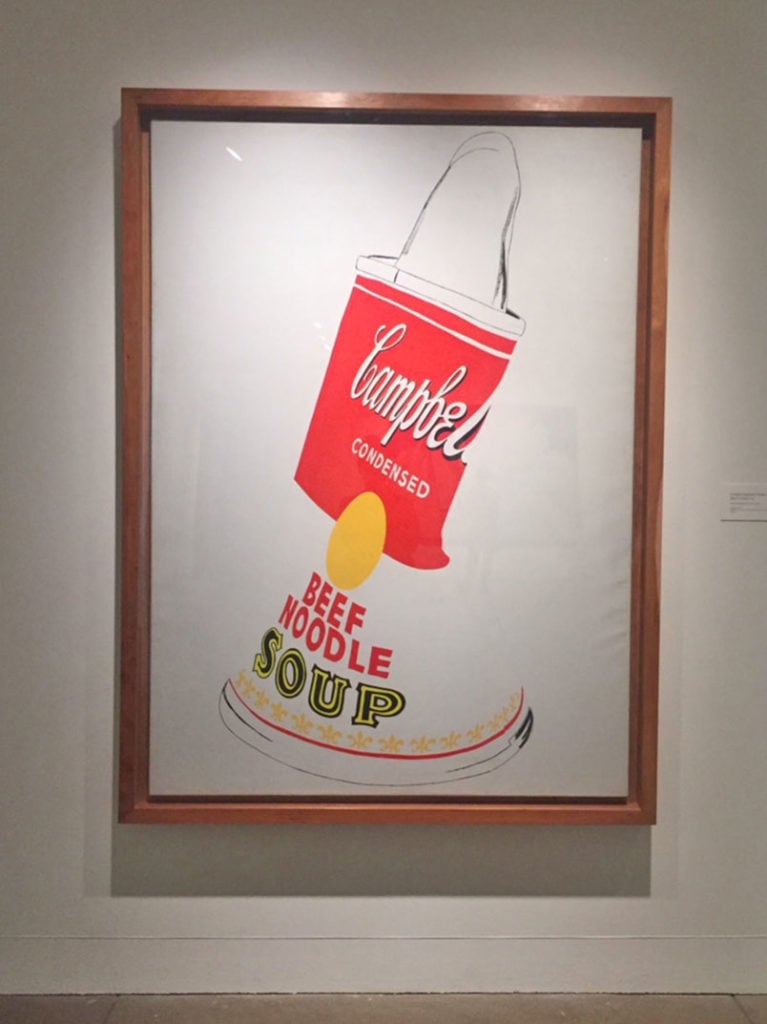

As North America’s largest museum dedicated to a single artist, the Andy Warhol Museum encompasses far more than just the Campbell’s Soup prints and multi-colored Marilyn Monroe portraits that Warhol is famous for (but don’t worry, those are in there, too).

The museum is situated in an old, seven-story building that was once a distribution center in the heart of Pittsburgh, Warhol’s hometown. It’s home to the most comprehensive collection of Warhol art and archives around the world, including paintings, sketchbooks, photographs, film, sculptures, and interactive exhibits.

The galleries are organized in chronological order from top to bottom, allowing museumgoers to completely immerse themselves in the story of Warhol’s life as it unfolds on each consecutive floor.

On the top floor, you can view some of Warhol’s early drawings, sketches, and ideas, including excerpts from two unpublished children’s books created with rubber stamps, pencil, and paper. Incorporating colorful designs and whimsical, imaginary elements, one book revolves entirely around the word “so,” while the other details a magical story about a house that comes to life at night to sneak off into a nearby town.

A New York state of mind

Warhol was born Andrew Warhola on August 6, 1928. He was the fourth child of Julia and Ondrej Warhola, who had emigrated to the U.S. from what is today known as Slovakia. Warhol’s move to New York City in 1949, after graduating from the Carnegie Institute of Technology (present-day Carnegie Mellon University), marked the start of his wildly successful career as an artist.

He started out as a freelance commercial illustrator, immediately appealing to clients as he was able to deliver creative ideas almost as quickly as he pitched them. “He was a quick study,” I read on one of the museum’s walls. “Given an assignment, he would turn in a brown paper bag full of drawings on the subject the very next day.”

It was during this period of his life that Warhol started to understand just how powerful advertising’s influence was. In fact, had it not been for this stint in commercial work, he may have never gone on to create the Campbell’s Soup art that launched him into the pop-art scene in 1962.

Interested in how products with strong advertising campaigns create a widely-shared American experience, Warhol drew inspiration from Campbell’s, trying to illustrate this landscape of growing consumerism. According to an excerpt in the museum, he chose this “quintessential American product” because it represented modern ideals: It was inexpensive, easily prepared, and available in just about any food market. Warhol claimed that he ate Campbell’s Soup every day for 20 years.

Pivot to video

Just one year after establishing himself as a fine art painter via the Campbell’s Soup can exhibit, Warhol shifted much of his focus to filmmaking. “People come to this museum every day and have no idea that Andy Warhol ever made any movies,” Grace Marston, an educator at the museum tells me. “But he actually made around 600 films over the course of his career.”

Today, the museum houses the entire output of Warhol’s filmography—which includes more than 4,000 movies and videotaped works. The sixth floor is completely dedicated to Warhol’s extensive, yet lesser-known, filmmaking career.

I head to the back wall of the dimly-lit film exhibit, where three of Warhol’s black-and-white silent films are projected simultaneously. Among the three is Sleep, the first movie Warhol created in 1963. As suggested by the title, it’s 5 hours and 20 minutes of footage of Warhol’s sleeping boyfriend, poet John Giorno. The camera shows different angles and emphasizes different body parts throughout the duration of the film, but Girono never wakes up.

People often walked out during screenings of his movies because they were bored to tears.

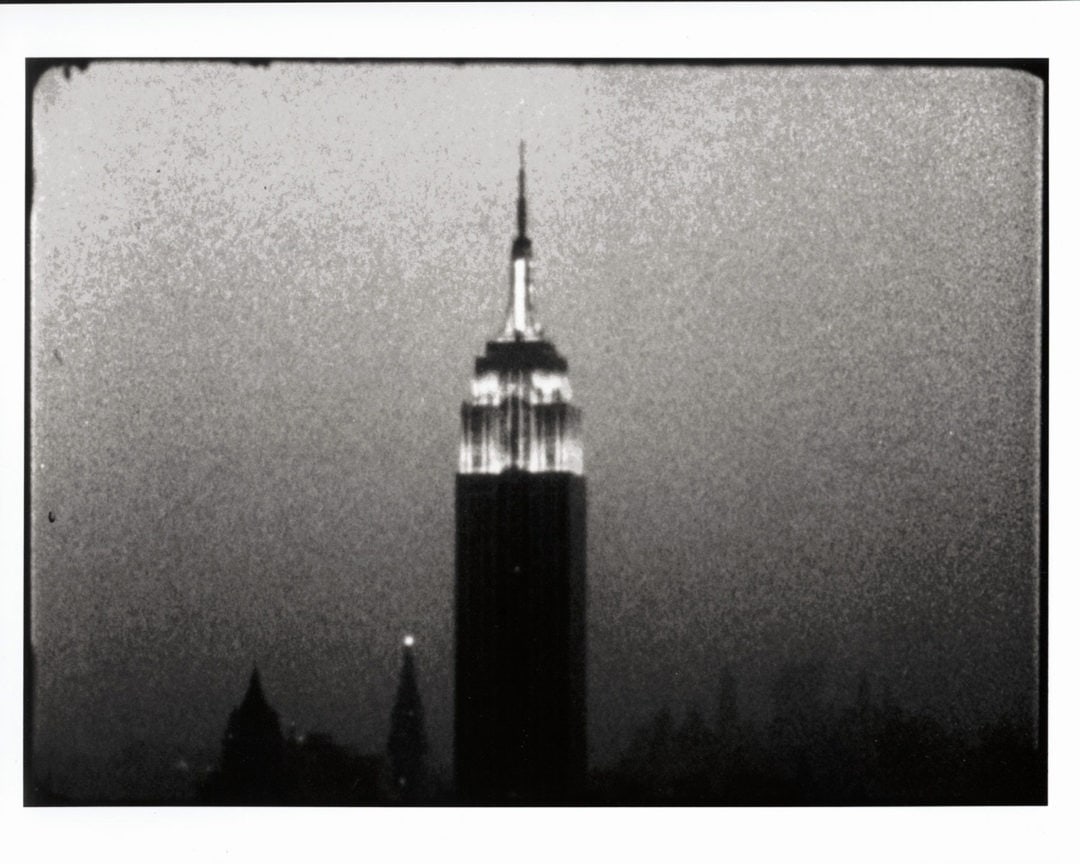

Sleep wasn’t the only bizarre film Warhol made. Empire shows 8 hours of still-shot footage of the Empire State Building and Eat is 40 minutes of a man eating a single mushroom. People often walked out during screenings of his movies because they were bored to tears, but Warhol was unfazed.

“With these films, he’s making the point that you don’t need an exciting story,” Marston explains. “You can just do whatever you were already doing in front of a camera, and that’s all it takes to make a movie. He’s taking these really ordinary, mundane images and elevating them into fine art.”

Screen testing

Following these offbeat films were Warhol’s “screen tests,” which were shorter, more personal, movie-like portraits that similarly aimed to elevate the ordinary. The concept was simple: Warhol would sit someone down and film them, straight on, for three minutes. After he finished filming, he would then stretch the footage into four minutes, slowing it down to really capture every minute movement and facial detail.

“When it’s shown in slow motion, you really notice every change in expression,” says Marston. “It gives you an idea of their persona just by watching them sit in front of a camera for a few minutes.”

Over the course of the 1960s, Warhol shot more than 500 screen tests of actors, writers, models, artists, musicians, and other interesting characters inhabiting New York City at the time. According to Marston, “It was kind of his way of collecting all of the beautiful faces and interesting personalities that stopped by his Silver Factory.”

At the Andy Warhol Museum, you can actually sit for your own screen test. A vintage 1960s film camera (with a webcam inside) lives in a secluded room near the film exhibit ready for public use. Sit for what feels like the longest three minutes of your life, and once you’re finished, the system sends you an email with a private link to your own personal screen test.

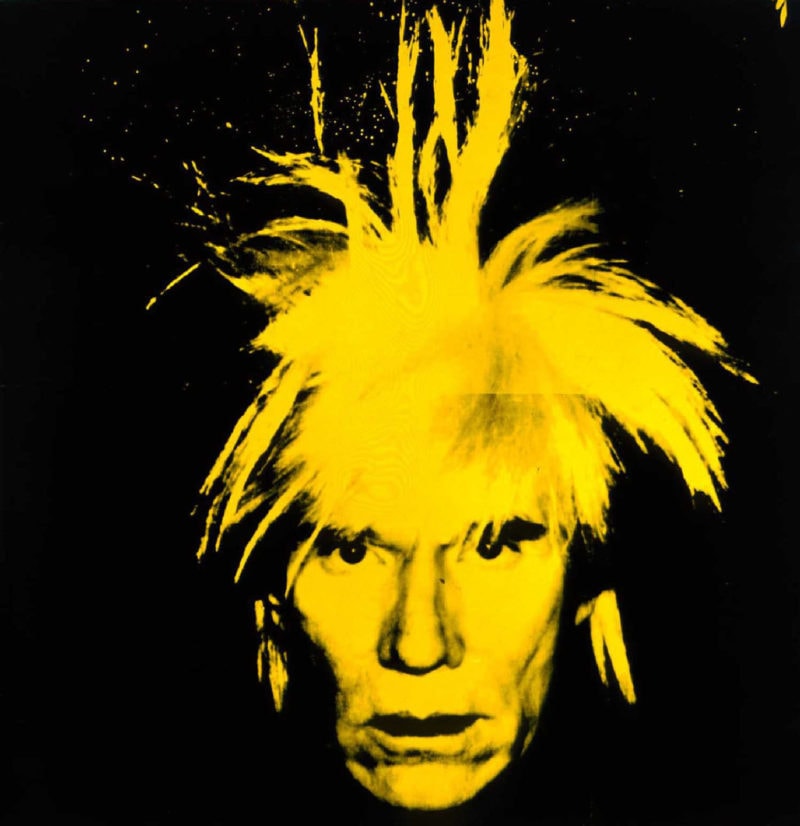

More than thirty years after his death in 1987, Warhol remains a legendary pop-art icon and one of the most influential contemporary artists of all time. The Andy Warhol Museum celebrates its 25th anniversary this fall, so there’s no better time to explore and immerse yourself in Warhol’s massive body of work.

If you go

The Andy Warhol Museum is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day except Monday, with half-price admission on Fridays from 5 to 10 p.m. Free gallery talks with museum educators take place daily at 11 a.m. and 3 p.m.