Edna “Mom” Davy anchored herself cross-legged on the minivan’s floor, sweater yanked tightly over her head. “I’m not going back up there,” she cried. The Davys had just completed the Bella Coola extension of Highway 20 in south-central British Columbia, Canada. The road, classified as one of the most dangerous highways in North America, drops an ear-popping 5,000 feet through hairpin bends and major switchbacks.

A passing driver had offered to pilot the Davys’ minivan back to Anahim Lake, at the start of the route, after William “Pop” Davy declined to re-weave the scenic, white knuckle-inducing route. But Edna continued to wail at every lurch and road lump, until they were parked safely at the top.

When the Davys’ told me about their trip, I thought to myself, “What’s the problem?”

It’s not until my husband George and I make the same descent in our 22-foot class C motorhome that I begin to understand Edna’s outburst. For 273 miles across the Chilcotin region, I happily photograph cattle, cow ponies, and split rail fences set against picturesque blue skies and scudding white clouds. I am lulled into complacency by rolling grasslands, jack pine forests, and a notable lack of supermarkets or fast food chains. But at Tweedsmuir South Provincial Park, the paved section of Highway 20 ends and the real “fun”—depending on who you ask—begins.

Download the mobile app to plan on the go.

Share and plan trips with friends while discovering millions of places along your route.

Get the AppGearing down

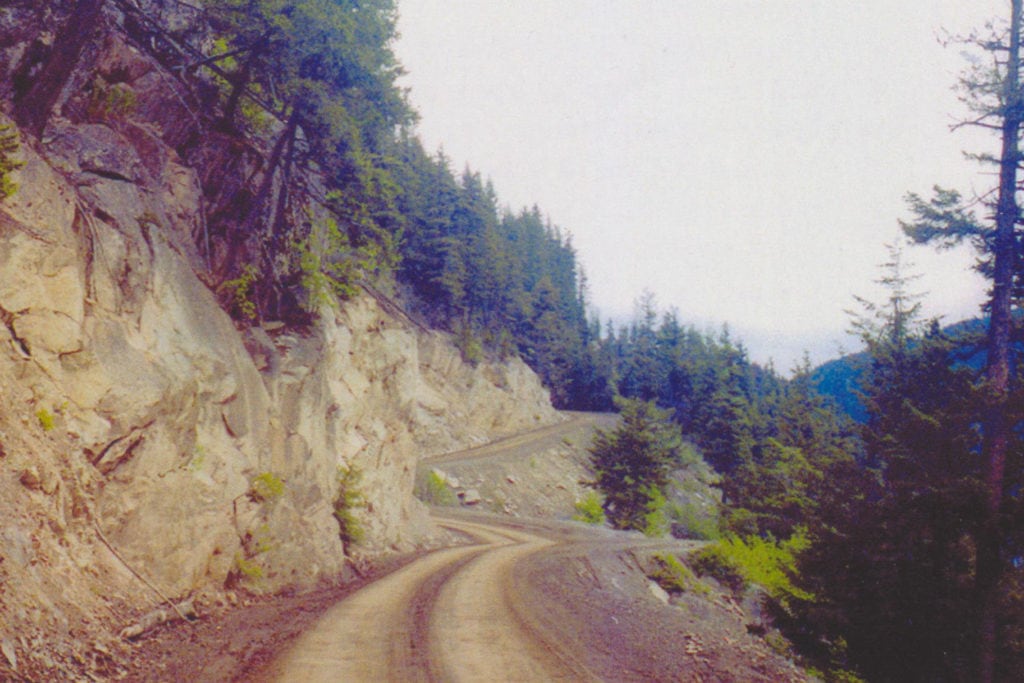

George gears down the engine to prevent the brakes from burning out down the 18 percent grades. Rocks crunch and spew from the tires while pebbles crash into the undercarriage; the cliffside drops steeply just inches from my side mirror. Two switchbacks totaling seven miles test our already-frayed nerves.

I yelp as my fingers dig into the dashboard. “Honey, this is beautiful,” George says calmly. “Look how high up we are. Take a picture.” I open my eyes long enough to see the cliffside disappear—there is nothing separating us from the valley floor except a few boulders and scrub pine. My legs ache from trying to apply brakes that aren’t there.

We pause and take in the view while a long delivery truck backs up, reverses, cranks its wheels hard, and pretzels around the bend. At one point the front bumper hangs precariously over the edge of the cliffside. George takes the opportunity to relay a bit of road trivia: “In 1972, Bob Patison was the first to deliver a mobile home down here,” he says.

It seems impossible to me, but Cory Patison of Patison Mobile Homes confirms that they did indeed navigate the Bella Coola with a 68-foot-long unit weighing 32,640 pounds pushing down against the truck’s tow hitch. “It took us most of the day,” he says. “We were also the first to haul a mobile home back up—equally difficult. The transmission and rear axles overheated, and it took us half an hour to wiggle around one hairpin.”

After a 13-mile descent that takes 1 hour and 25 minutes, we stop to relax at the Gnomes Home Campground in Hagensborg.

The “impossible” road

At the Kopas General Store we learn that this harrowing road was built by the citizens of Bella Coola and Anahim Lake after the British Columbia government deemed the project “impossible.” A group led by Cliff Kopas and the Bella Coola Board of Trade raised and borrowed funds, and procured a small grant. In the beginning, a dynamite powder crew comprising just two men, two air compressors, and two jackhammers blasted and hammered a channel up the cliff face.

In the early 1950s, Ike Sing, owner of a general store in Anahim Lake, promoted the road build and convinced Thomas Squinas, an expert trapper and guide, to blaze a trail through muskeg and mosquitoes via Tweedsmuir Park. For two years, base camps filled with donated supplies moved ever-shakily upwards. Men backpacked and horses hauled supplies over rock and mud trails. Women and children tossed stray rocks over the cliffside. Jackhammers required a change of drill bits every two feet. A TD18 bulldozer slipped off the cliffside twice. It was pinned in place and winched back up to relative safety—it may have been the first piece of equipment to slip, but it wasn’t the last.

In September 1953, two machines touched blades in a symbolic meeting of top to bottom. In 1955, Minister of Highways Phil Gagliardi admitted that the town had done what experts said couldn’t be done, and celebrated the road’s “official” opening. He also paid off the outstanding shortfall of $8,700—the route had cost $1,300 per mile to build, not including the uncounted hours of volunteer labor.

Surviving the Bella Coola

Since 1955, the road—once no more than a cliffside goat path—has been improved as much as the geography will allow. But it is still only wide enough for one vehicle and there are no guardrails protecting vehicles from the steep drop.

The town of Bella Coola may be tiny, but it’s full of history. It’s home to the Bella Coola Valley Museum, Clayton Falls, scenic hiking trails, grizzly bears, ancient petroglyphs, and modern-day grocery stores and gas stations. For those visitors unable or unwilling to tackle the upwards trek to Anahim Lake, a ferry is available from June to September on alternate days.

After a hearty breakfast at the Valley Inn Hotel restaurant, George suggests that I drive us back up the Bella Coola cliffside highway. When I reply, “I’d rather walk than drive, just give me a head start,” George hops behind the wheel and begins the trip uphill in low gear.

When we’re back home—and on more solid ground—I reflect on our trip while sipping from a souvenir coffee mug. It states, “I survived the Bella Coola Highway. You can too.”

If you go

The Bella Coola part of Highway 20, also known as the Hill, runs between Anahim Lake and Bella Coola, British Columbia.