Real estate is not cheap on Long Island. The closer you get to the multi-million dollar mansions of the Hamptons, property values skyrocket into the stratosphere. Even Grey Gardens, once the notoriously ramshackle home of the eccentric Beale women (and their raccoons), has recently received a ritzy makeover. It would seem that nothing is sacred and no structure is safe from the wrecking ball on the densely populated island east of Manhattan—that is, until you drive along Route 24 and the Big Duck appears on the horizon.

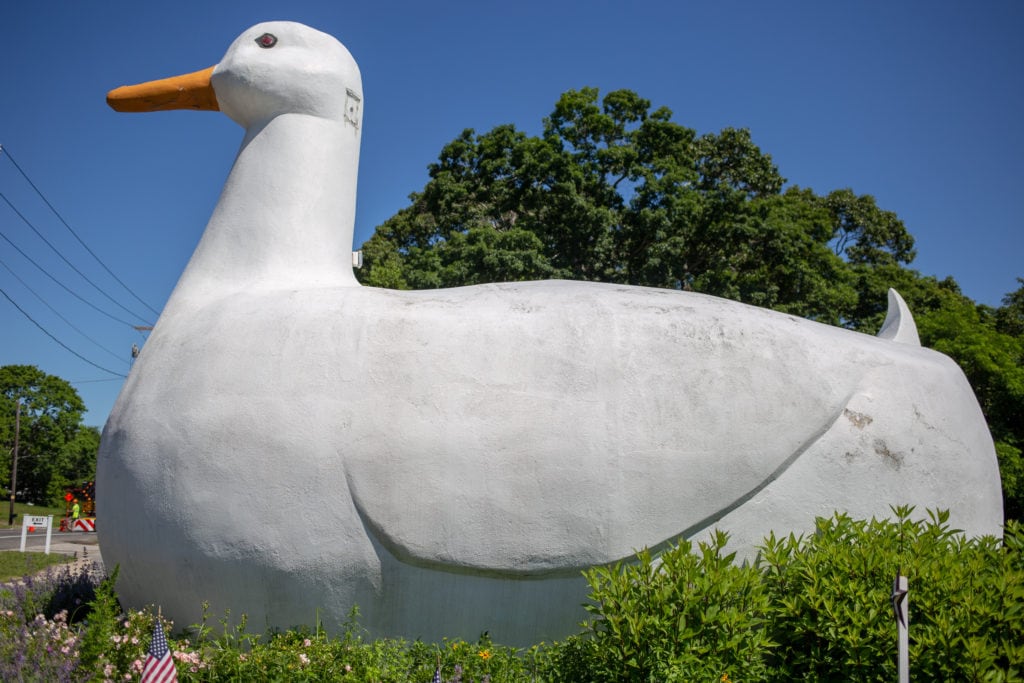

Built in 1931, when eastern Long Island was full of duck farms instead of celebrities, the Big Duck is, quite literally, a big duck. It was originally built to sell live and cooked ducks, but it has become a world famous example of novelty architecture. There are other so-called “Duck Buildings” in the world—large coffee pots, big oranges, and the Longaberger Basket, for example—but there is only one Big Duck.

-

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

They say you never forget your first, and I first visited the Big Duck on a cold day in March of 2017. The ground was covered in snow and the wind was fierce, but the duck didn’t seem to notice. It’s not alive, of course, but I am and I’d been anticipating this moment for years. When I was growing up in Ohio, I dreamed of one day visiting every whimsical building still standing in the U.S., and the Big Duck was number one on that list.

Fowl facts and fiction

I return to the duck on a hot and sunny weekday in June and I receive an equally warm welcome when I enter the small souvenir shop. The man on duck duty introduces himself to me as Mr. Tee, “like the television star but spelled T-E-E.” He lives across the street and raises parrots. Mr. Tee—along with a handful of other volunteers—opens the shop and chats with visitors a few days a week. His official title is “Chief Sitting Duck,” he explains from the plastic lawn chair upon which he remains perched for most of my visit.

In 1931, inspired by their travels in California where they visited a large coffee-pot-shaped roadside cafe, Long Island duck farmers Marin and Jeule Maurer decided to build their own novelty building in the town of Riverhead, New York. They hired a carpenter and two set designers to construct the Big Duck, which was modeled after one of their live ducks. In 1936, the Maurers relocated their thriving shop to Flanders, a Southampton hamlet so small that it still doesn’t have its own zip code, and called the surrounding land the Big Duck Ranch.

The wooden frame (visible through a window in the ceiling of the shop) is covered by wire mesh and painted concrete. Measuring 30 feet from beak to tail, the 10-ton, brilliantly white duck has two Model T tail lights for eyes and a bright orange beak. The eyes, which still glow red at night, apparently scared some people when they were first illuminated. “People who believed in witchcraft thought it was a satanic duck,” says Mr. Tee.

Mr. Tee presents a lot of questionable statements as fact, but when you’re standing (or sitting) inside of a Big Duck, anything seems possible. His favorite story, which he repeats word-for-word to every visitor is about a big egg that was discovered under the duck when it was moved. “They took the egg to Dinosaur Island,” Mr. Tee says with complete sincerity, pointing to a newspaper clipping. “This is the egg they used to clone the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park.”

According to the New York Times, “the duck’s egg, [was] an accessory added in 1987 during a $30,000 makeover. Sadly, it cracked for real in the course of the duck’s ill-fated, and unpopular, move to county parkland in 1988.” Though, Mr. Tee’s version is more befitting of the fantastical structure.

An architectural icon

While not as large as the Longaberger Basket or as interactive as a drive-through donut, the Big Duck inspired architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown to coin the term “Duck” in their 1972 book Learning from Las Vegas. The blanket term Duck is now used to describe any sculptural building created in the image of a product or service that it provides—it is both structure and sign combined.

“Designed to mesmerize passing motorists and entice them ultimately to a purchase, Ducks are fantastical while retaining their purely practical intentions,” according to a brochure provided by the Suffolk County Department of Parks, Recreation, and Conservation.

Architect James Wines’ Duck Design Theory explains that in Duck buildings, “Form follows fantasy not function, for architecture that cannot offer fantasy fails man’s need to dream.”

The design of the Big Duck was officially trademarked by Maurer immediately upon its completion in 1931. The Big Duck Ranch received its own trademark the following year, although the Duck still doesn’t have its own address. Mr. Tee says that people blindly following their GPS often drive right past it. “They say, ‘Whoa, was that the Big Duck?’ and have to turn around.”

“Form follows fantasy not function, for architecture that cannot offer fantasy fails man’s need to dream.”

Every year, people who appreciate a little quack with their quirk—including VW van enthusiasts and Parrotheads—gather to photograph their vehicles and themselves in front of the Big Duck. However, Mr. Tee urges visitors to stay a while and learn the Duck’s history instead of simply snapping a quick selfie. “This is more than just a place to stop and take photos, it’s an architectural icon,” he says.

Since Venturi’s death in 2018, more and more architects have flocked to the Big Duck from all over the world. They come to pay their respects, leaving stones and mementos on the “Enter” sign in the parking lot.

On the wall behind the counter, visitors have left photos from their travels to other notable examples of novelty architecture, many of which haven’t had the same luck as the Duck. The hot-dog-shaped Tail O’ the Pup, a big Brown Derby hat in Los Angeles, and Coney Island’s elephant hotel have respectively been relegated to storage, modified beyond recognition, or demolished.

Eight million ducks

In 1873, four ducks imported from China launched a multi-million dollar duck farming industry in eastern New York. Long Island’s climate, miles of waterfront land, and proximity to New York City made it the perfect place to raise Pekin duck. The Long Island Duck was once a staple in “white-tablecloth” restaurants around the country and the Pekin duck, coveted for its savory and tender meat, made Long Island as famous for ducks as Idaho is for potatoes or Maine is for lobster.

In the 1940s, 100 farms on Long Island produced six to eight million ducks every year. In the 1970s, stricter environmental laws regulating water pollution reduced the number of duck farms to 24, and today only one remains: the Crescent Duck Farm, located in Aquebogue.

With the exception of the ducks that come from Crescent Farm, the majority of what is still sold as “Long Island Duck” now comes from Michigan. That doesn’t stop people from calling the Big Duck, attempting to order a cooked duck for dinner. “I tell them they’re 40 years too late,” Mr. Tee says.

The structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1997, but the Big Duck’s fate hasn’t always been secure. “What do you do with a big duck when there’s no more duck farming?” says Mr. Tee.

Save the Duck

People have different memories of the Big Duck depending on where they grew up and when they first passed the Long Island landmark. And they’re not misremembering—the Big Duck has been moved three times (to two different locations) during its lifetime.

When the Maurers retired in 1951, the shop was operated by two different families before it was sold to Kia and Pouran Eshghi in 1982. The Eshghis intended to turn the land into an artists’ commune, but they ran into zoning restrictions and sold the land to developers a few years later.

When threatened with the possible demolition of their beloved duck in 1987, the people of Flanders rallied. Their “Save the Duck” campaign was successful in persuading the Eshghis to donate the duck to Suffolk County, and in 1988 the duck was moved a few miles to the Sears Bellows County Park. The town of Southampton purchased the still-undeveloped Big Duck Ranch land in 2001 and the Big Duck returned home in 2007.

I chat with Mr. Tee for more than two hours, during which several families stop by the Big Duck to snap photos. But most of them also come inside, if only to see what could possibly be inside of the duck. It ceased to be a poultry shop in the ‘80s and has contained duck-related souvenirs (tote bags, enamel pins, rubber ducks, etc.) ever since. I overhear one woman tell Mr. Tee, “My whole life I’ve been driving past this duck and today I finally thought, ‘we’re going in.’”

-

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan -

Photo: Alexandra Charitan

More than 10,000 people pull off the road every year on their way to the Hamptons to visit the store and museum, which also includes a collection of newspaper articles about the Duck, books on local history, artwork, and other hand-crafted items. On the first Wednesday after Thanksgiving, people gather around the festive fowl—draped in pine garland and colorful lights—for the annual holiday lighting.

The Duck is open year-round, but Mr. Tee urges visitors to cut the volunteers some slack. “If you arrive and the duck is closed, it’s because one of us didn’t get out of bed in time.”

If you go

Although the Big Duck is open year-round, Monday through Friday and Sunday 10 a.m. to 5 p.m, and Saturdays 10 a.m. to 3 p.m, it is advised that you call ahead (631) 852-3377 to make sure someone will be there.