During the racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd, protests raged in Richmond, Virginia, in the summer of 2020. A prominently displayed statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee perched on Richmond’s tree-lined Monument Avenue was defaced, and became a rallying post for protesters. A year later, and more than 130 years after it was installed, the statue of Lee was removed from its pedestal. By the end of 2022, the last of the city’s public Confederate monuments were removed.

So it appears the wheels of progress turn slowly in the former capital of the Confederacy. Change, however, is afoot in the tourism sector. Richmond’s rich Black history goes beyond slavery—and that shift in narrative can be credited in large part to the resourcefulness and sheer willpower of local African American historians, tour guides, and entrepreneurial culture-keepers ensuring that the wins and contributions of Black Richmonders are championed.

Black joy

Free Bangura, founder of Untold RVA, is a daughter of this new revolution committed to commemorative justice, and she is determined to keep Richmond honest about its Black past and present. We met during my tour of the city’s Black cultural offerings last fall.

Over lunch at the soul food staple Mama J’s, where I order flaky fried catfish and she orders her fried chicken “fried hard,” Bangura, a self-proclaimed sacred placekeeper, speaks about African Americans who can trace their lineage to the auction blocks in Richmond.

But that’s not where the story ends.

“We are not seeking to traumatize folks when they come to the city of Richmond, but to amplify their ability and connection to these very inspiring stories of those who pushed against the systemic inequity that they were born into,” she explains.

“That freedom narrative can inspire generations to continue on in the same direction of Black liberation, Black joy, Black girl magic, Black power, Black love, Black excellence, and all of those good things that come when you’re able to freely experience the things that other people have worked so hard for generations to submerge.”

Untold RVA offers free and concierge urban exploration experiences such as “Keepers of the Light,” a series of street light installations where visitors call a listed phone number and get a progressive hip-hop-backed lesson about what happened there “as it relates to Black freedom.”

“The Virginia Way”

On an information-packed and fast-paced walking tour of the city’s historic Jackson Ward neighborhood, the hub of commerce and social life for Black residents at the turn of the century, historian Gary L. Flowers doesn’t mince words about what he calls “the Virginia way.”

“It’s the willful suppression of Black history for a counter narrative,” asserts Flowers.

A fourth-generation Richmonder, Flowers is a nattily-dressed and passionate guide. At the end of the 20-stop tour, we gather at a handsome bronze statue of hometown “shero” Maggie L. Walker in downtown Richmond. Although Walker was a prominent community leader, civil rights activist, and the first African American Black woman to charter a bank, in the wider scope of American history she remains a hidden figure.

“They couldn’t believe that a Black woman had all of this empire in the capital of the Confederates,” Flowers says. “So you can’t promote Mrs. Walker as a millionaire, an entrepreneur, and a badass unless you want other Black girls to want to do the same thing. That’s why she is the most unheralded woman in American history.”

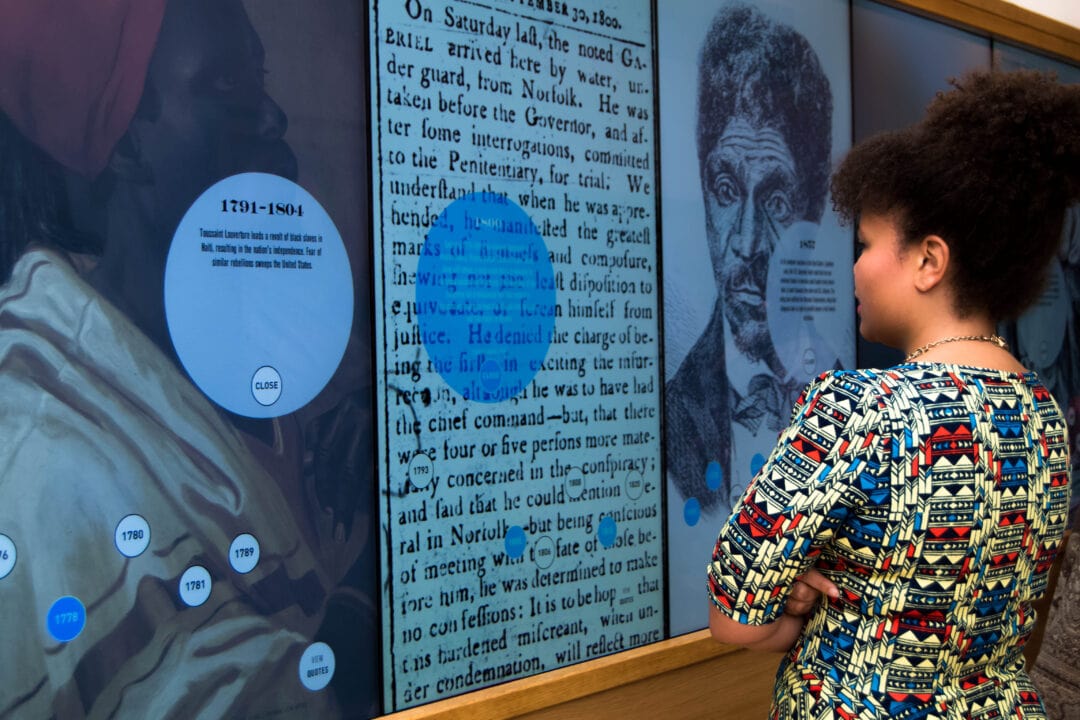

Elvatrice Belsches was commissioned by the National Park Service to create the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site podcast tour of Historic Jackson Ward. The author of Black America Series: Richmond, Virginia also curated the exhibition Forging Freedom, Justice, and Equality: A Survey of the History of the Black Experience in Virginia at the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia (BHMVA) in commemoration of the museum’s 40th anniversary. The exhibition runs through April 2023 and showcases compelling stories and rare artifacts.

“My goal was to expand the narratives and illuminate the extraordinary accomplishments of Blacks in Virginia across various disciplines,” Belshes says. “Although the period of enslavement, the massive slave trade, and the Civil War are well-documented, I realized that the free Black experience, the central role of the Black Church, and the history of Virginia’s historically Black colleges and universities—and other topics—needed to be placed before the general public.”

Freedom fighters

There’s no escaping the hard truth that in 1619, the first Africans in America arrived in Virginia and were sold into bondage; from the 1830s through to the Civil War, Richmond was one of the largest slave markets in the U.S. But Elegba Folklore Society president and artistic director Janine Bell seeks to shift from a disempowered narrative to a proud and empowered one. Named after an African deity known as “a trickster,” Elegba presents educational and artistic programs, and offers guided cultural history tours.

“We cannot and we will not continue to tell the story or begin the story of Africans in America incarcerated from the start,” says Bell. “That’s a part of the problem of systemic racism. So we begin the tour here so people can get a different kind of sensibility and we can talk about the American enslavement of African people in our right mind. Even just that touch, I think, makes a difference—at least we hope so.”

The nonprofit cultural arts organization’s Afrocentric storefront on Broad Street is filled with imported artwork, books, clothing, and accessories. When I visit with other journalists, Bell and her daughter give an ancestrally-rooted performance. Accompanied by live drumming, through chants and songs they connect the diasporic dots between Black music from Africa to Motown to hip-hop.

Before I leave the shop, beaming and wearing a new addition to my collection of beaded bangle bracelets, I ask Bell if the freedom fighter work she’s been doing for more than 30 years takes a toll.

“Yes, it’s an uphill walk every day,” she says. “That’s not to say that the country is not making progress—it’s not fast, but that makes our legs stronger. The endurance and resilience, that’s a quality that our ancestors had.”