State parks, as we know them, were born in the 1930s, when roughly 800 parks were built in the U.S. using money and workers from federal job-creation programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The result was something new and wonderful, a system of easily accessible natural spaces where people could retreat, relax, and enjoy their favorite outdoor activities.

Unfortunately, many of those spaces, particularly in the South, were unavailable to Black Americans, who were barred from the parks by segregationist laws and policies. In an era when separate but equal was the law, some states built one or two state parks designated for the use of Black residents. This meant that Black people often had to travel great distances to enjoy what was available close to home for white residents.

With the end of segregation as government policy, most Blacks-only parks were desegregated or merged into nearby state parks. Because of this, a great deal of history, memory, and sense of community around these parks were lost over time. Once distinctive and vital centers of life in the Black community, the now-integrated facilities became just like every other state park.

In recent years, government agencies and private groups have worked to illuminate the history of former Blacks-only parks. Today, nearly 70 years after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision struck down separate but equal, a tour of seven formerly segregated state parks offers a blend of relaxation, adventure, and thought-provoking history.

1. Lake Murray State Park, Ardmore, Oklahoma

Lake Murray State Park wasn’t a Blacks-only state park, but instead a segregated facility. The park was designed for Oklahoma by the National Park Service in the 1930s and built by several New Deal agencies.

Lake Murray opened with two whites-only camping areas and a “Negro” camp in a less desirable location, with lower-quality facilities. While this was the only permanent campground in Oklahoma open to Black residents, Blacks were barred from using many of the park’s other amenities. Lake Murray remained segregated until the 1960s.

Today, the park features notable examples of parkitecture, the rustic architecture and ideology common to national and state parks built in the 1930s. Lake Murray’s architects designed its amenities to disappear into the landscape. The designers hid trash receptacles, and drinking fountains spouted from rocks.

A stone structure called Tucker Tower was reportedly intended to be a summer home for the governors of Oklahoma, but now serves as a nature center with stunning views of the entire park. A small display in the tower features vintage maps of the park and offers a brief overview of Lake Murray’s segregated era.

2. Historic Cherokee at Kenlake State Resort Park, Hardin, Kentucky

Known today as Historic Cherokee at Kenlake State Resort Park, Cherokee State Park is an example of what might be called a mirror segregation park. Cherokee opened in 1951 as Kentucky’s first and only state park for Black residents. The 300-acre park sat directly across Kentucky Lake from whites-only Kenlake State Park, which was built simultaneously. There were no trails or roads connecting the contiguous parks.

Cherokee’s location and top-notch amenities made the park wildly popular with Black Americans who came from the Midwest and South to enjoy its beauty and activities. Kentucky’s 1963 integration of state facilities started a slow decline for Cherokee. The park was stripped of many amenities, including cabins, which were trucked or floated across the lake to Kenlake. Eventually, Cherokee was merged with Kenlake.

The Friends of Cherokee State Historic Park was formed to support, preserve, and highlight the history of the former state park. The group recently built the deeply-symbolic first hiking trail to connect the two formerly segregated parks. The park’s history was explored even further in the 2022 documentary A Legacy Lost & Found: Segregation in Recreation.

3. T.O. Fuller State Park, Memphis, Tennessee

Located near Graceland on the south side of Memphis, this 1,138-acre urban woodland opened in 1938. It was among the first state parks east of the Mississippi River built specifically to provide “separate but equal” recreation facilities for Black people. The CCC-built facility was initially named Shelby County Negro State Park. The state later changed the park’s name to honor Dr. Thomas O. Fuller, a prominent leader of the Black community.

Today, Fuller is a popular destination for a wide range of activities, everything from hiking to swimming to picnics to birdwatching. According to Tennessee State Parks, T. O. Fuller State Park “works to preserve the park’s CCC history and demonstrate how early park development fits within the context of the African American civil rights movement in Tennessee.”

4. Booker T. Washington State Park, Chattanooga, Tennessee

You’ll need to drive nearly the length of Tennessee to reach the only other state park open to Black residents of the Volunteer State during the Jim Crow era.

Booker T. Washington State Park sits just outside Chattanooga alongside Chickamauga Lake. Like its sister segregation park, this facility was built in the 1930s with help from several federal agencies, including the Tennessee Valley Authority, which created the lake, and the CCC, which used one of its all-Black units to build the park. While construction began in the 1930s, Booker T. Washington State Park for Negroes wasn’t completed until closer to 1950. It remained segregated until 1962.

While fishing and boating take center stage at this 353-acre park, it’s also a magnet for local mountain bikers, who love the park’s challenging 6-mile bike trail. The ample picnicking facilities and short hiking trails make this a popular day trip destination for Chattanooga-area residents.

Visitors who want to learn more about the park’s namesake and history can take a self-guided tour highlighting Booker T. Washington’s life. Interpretive displays in the front office chronicle the park’s development, including its construction by a Black unit of the CCC.

5. George Washington Carver Park, Acworth, Georgia

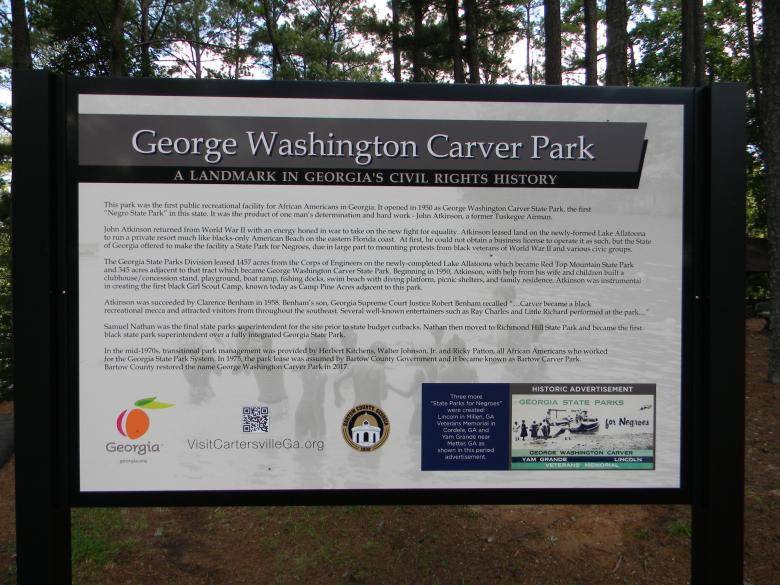

A 90-minute drive down Interstate 75 South brings you to another segregation-era park. Now a county park, this facility opened in 1950 as George Washington Carver State Park, a Blacks-only recreation area just down the road from whites-only Red Top Mountain State Park.

Set on the shore of man-made Allatoona Lake, Carver was known in local Black communities as “The Beach.” Former Tuskegee Airman John Loyd Atkinson, who pressed for the park’s creation, oversaw Carver as Georgia’s first Black park superintendent.

In addition to its natural attractions, Carver was a popular summer music venue that hosted stars like Ray Charles and Little Richard. Carver also played a role in the lives of two civil rights titans; Coretta Scott King was a regular visitor, as was Andrew Young, who learned to water ski on the lake.

In the 1970s, Georgia transferred the now-integrated park to Bartow County, and it was renamed Carver Bartow Park. In 2017, the park returned to its original name. Today, it remains a popular spot for boating and picnicking for all Georgians.

George Washington Carver Park is part of the Cartersville-Bartow County African-American Heritage Trail, which features other landmarks tracing the history of Black Americans in the region.

6. Jones Lake State Park, Elizabethtown, North Carolina

North Carolina’s first state park for Black residents was built during the Depression as a Farm Resettlement initiative. These New Deal projects bought farmland from struggling farmers and resettled the families elsewhere.

Jones Lake opened in the summer of 1939 with a beach, a bathhouse, a snack stand, and picnic facilities. The park was an instant hit with the Black community, despite lacking the amenities that could be found at the nearby whites-only Singletary Lake State Park. In the 1950s, DeWitt Powell became the first Black superintendent of Jones Lake, where he created a family-friendly and meticulously maintained natural space for North Carolina’s Black residents.

Nearly 60 years after the state’s parks were integrated, Jones Lake remains a favored spot for Black residents, who gather for family reunions and church outings.

7. Twin Lakes State Park, Green Bay, Virginia

In the mid-1930s, an all-Black unit of the Civilian Conservation Corps built two dams in Central Virginia. Their efforts resulted in Goodwin Lake and Prince Edward Lake, which were designed to provide recreation areas for Virginians.

In 1948, Maceo Conrad Martin, a Black Virginia resident, sued the state after he was denied admittance to a state park. In a move that reflects the era’s realities, his suit didn’t seek integration of the state’s parks but rather the creation of a “separate but equal” outdoor recreation facility for Black Virginians. Two years later, Virginia upgraded the existing bare-bones Blacks-only Prince Edward recreation area to create its first state park for Black residents: Prince Edward State Park for Negroes. The new amenities included an enlarged swimming area, expanded parking lots, new roads, cabins, a bathhouse, and a concession area.

Prince Edward was a popular destination for both outdoor and social activities, including summer dances. The park was also an important source of seasonal jobs for young Black people, some of whom came from out of state to work as lifeguards and rangers.

In the 1970s, Prince Edward was merged with Goodwin Lake, a nearby whites-only recreation area, to create an integrated park. Despite the official end of segregation, Black and white people largely stayed in the same areas that they occupied before the merger. In 1986, the park was renamed Twin Lakes State Park.

Plan your trip

More resources

Want to learn more? Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South by William E. O’Brien is the definitive guide to Black state park history.