“If you don’t behave, I’m going to send you down to Milledgeville” was a common threat in the first half of the 20th century for men in Georgia to level against the women in their lives. Milledgeville was shorthand for Central State Hospital, once the country’s largest mental institution.

But for some, it was more than an empty threat. Men were able to have their wives or daughters committed—often against their will. According to Atlanta Magazine, “thousands of Georgians were shipped to Milledgeville, often with unspecified conditions, or disabilities that did not warrant a classification of mental illness, with little more of a label than ‘funny.’”

One of those women was my great-grandmother. I am now the same age that she was when she was first committed. When Central State Hospital opened for guided tours in early 2020, I went to see for myself the place where she had been confined for much of her life.

Committed

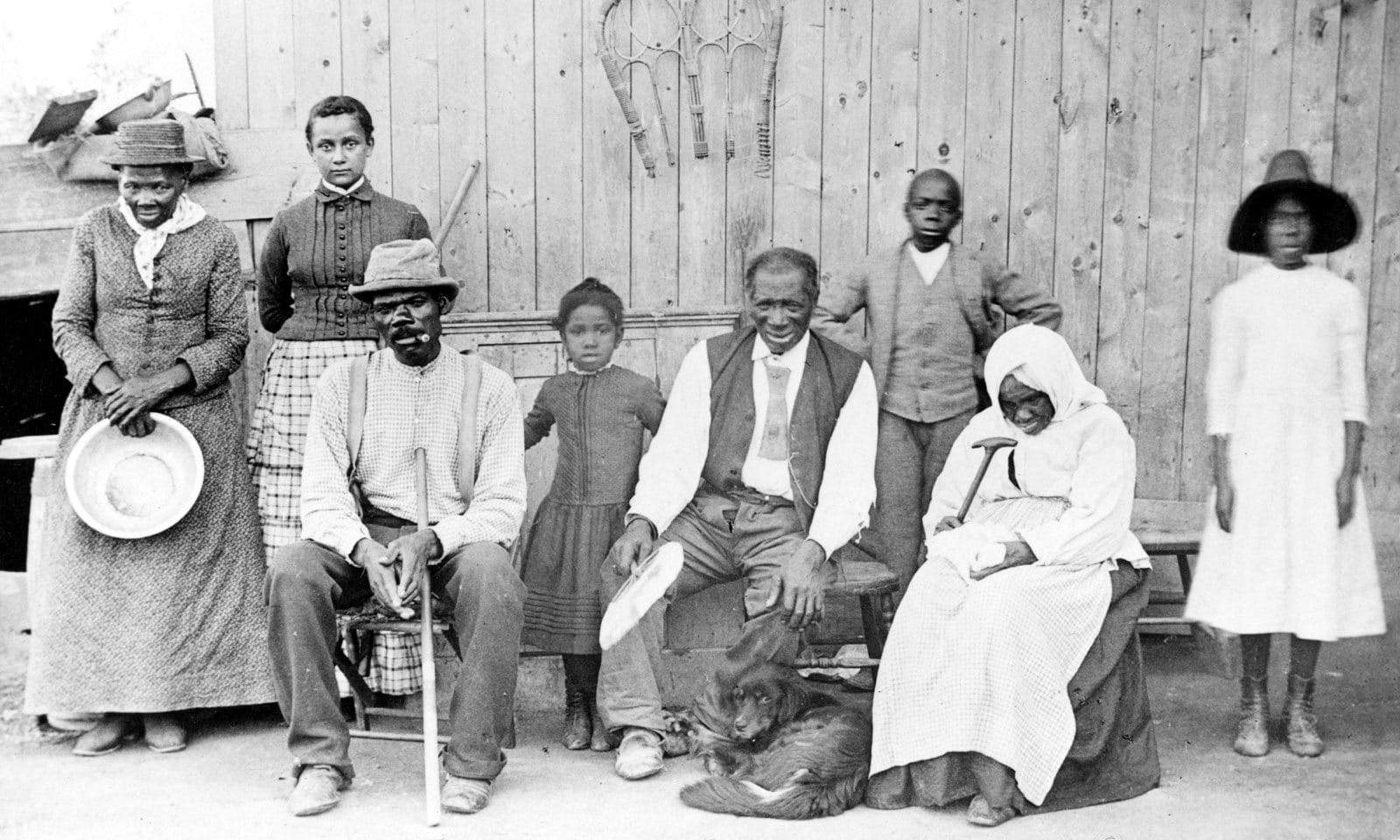

Stories about my great-grandmother were always part of family lore, but she was spoken about in hushed tones. It wasn’t until the rise of online ancestry websites that I learned more about her life through messages with distant relatives and records requests.

She was married by age 20, living in rural north Georgia with her husband and their two children. By age 30, she was an “inmate” at Central State Hospital, according to census records. She was diagnosed with schizophrenia, a term that at the time was a catchall for a number of conditions, including postpartum depression and other disorders.

She remained at Central State until the 1960s when 12,000 patients were discharged under Georgia’s Governor at the time, Jimmy Carter. Some patients went home to live with family members but my great-grandmother was moved to another facility where she spent her remaining years. She died at age 76, nine years before I was born.

Last stop: Milledgeville

Central State Hospital opened in 1836 as the “State Lunatic, Idiot, and Epileptic Asylum” in Milledgeville, a town located two hours southeast of Atlanta, not far from what was then the state capitol on the last stop of the rail line.

A far cry from private facilities that resembled resorts more than hospitals, Central State developed a notorious reputation, performing lobotomies and shock therapy. Patients were segregated into dorms based on their gender, race, and area of origin, not their respective conditions.

In the 1950s, following the trauma of World War II, there was reportedly one medical professional for every 100 patients at Central State, with a total population of 13,000 patients. In 1959, Atlanta Constitution reporter Jack Nelson wrote a Pulitzer Prize-winning exposé about how the inmates were truly running the asylum, leading to much-needed reforms.

Abandoned

After making the drive from my home in Atlanta, I park at the Milledgeville visitor center where, due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, I promptly have my temperature taken. I join a small group on a cherry red trolley; we sit in alternating rows to allow for social distancing on the tour led by former Central State public affairs officer Kari Brown. As the vehicle winds through backroads, I wonder in which of these buildings my great-grandmother might have resided.

During a previous visit, I saw local university students playing frisbee on the pecan grove that sits at the center of the hospital campus. Today, the grove is empty. The majority of the once-impressive structures—200 in total—are boarded up and at risk of collapse, with security patrolling to keep out urban explorers and curious onlookers.

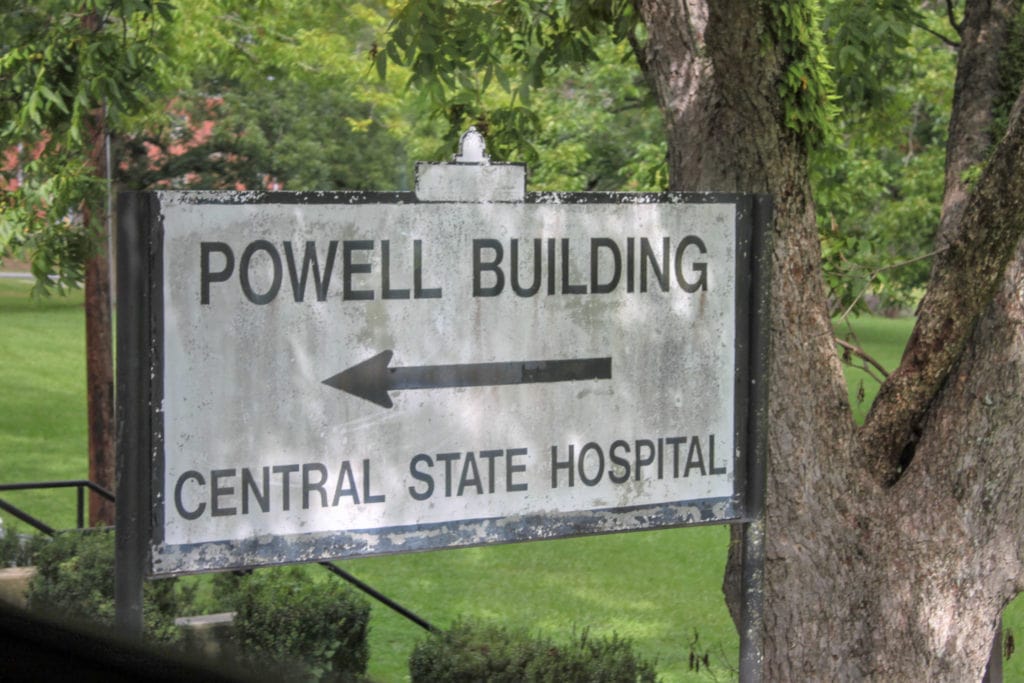

We pass the Walker Building—the oldest at Central State—with its sunken roof, and the Powell Building, a bright white domed structure that served as the administration building.

Two now-defunct prisons are covered in vines and resemble something out of The Walking Dead. The trolley comes to a stop at Cedar Lane, one of three onsite cemeteries. Neat rows of metal posts form a square, but they aren’t individual grave markers. Underneath sits a mass grave containing the remains of more than 10,000 unidentified former patients. An angel serves as a memorial to the unnamed dead, and advocacy groups have been working to re-identify them.

Parts of Central State are still in use, including the industrial kitchen that was at one time the largest in the world. The former auditorium is used by Georgia Military College and the Payton Cook Building is now a forensic inpatient facility.

A local group is currently trying to turn the space into Renaissance Park, a multi-use facility for local businesses, but the future of the remaining buildings is unclear.

If you go

Tours of Central State Hospital are available through the Milledgeville Visitor Center. They are held twice daily on two days per month. The tours last two hours and tickets are $30. Masks are required and there are no restroom stops. No food is allowed. Brochures are available in the visitor center for a self-guided tour. Keep in mind that security guards are on patrol, so stay on the sidewalk.