On a crisp November day, I park my car on the side of a San Joaquin Valley dirt road and cut the engine. The air, previously filled with the sounds of a blaring road trip playlist, is now silent and still. As I step out of the car, I hear only the sound of cows mooing and birds cawing in the nearby wildlife refuge. I stand in the center of the former town of Allensworth, the first town in California established exclusively by Black people, and feel calm.

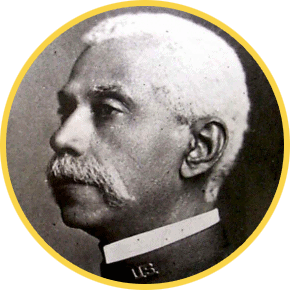

The historic town of Allensworth, now the Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park, is named after Colonel Allen Allensworth, the first Black lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army. The state park, founded in 1974, is the only in California dedicated exclusively to Black history. Once home to more than 300 residents, the preserved town now boasts dozens of buildings, outhouses, and pieces of farm equipment, alongside a visitor center, picnic benches, and a campground.

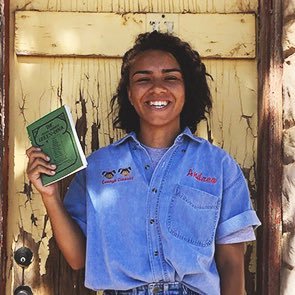

“Allensworth is a huge part of California history,” says Sasha Biscoe, president of non-profit Friends of Allensworth. “It’s the offspring of Jim Crow, it’s the continuation of what happened to African American people and why African American people had to take the stances that they did. Building a Black town in Allensworth—like Black people did all over the United States—was a way to be free from discrimination, hatred, abuse, and lynchings. It was a place of solace.”

Emancipatory beginnings

Colonel Allensworth was born into slavery in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1842. When Allensworth was a child, a Quaker neighbor taught him to read and write, sparking a lifelong love for education. Allensworth was sold twice to new owners in Memphis and New Orleans, where he was repeatedly whipped for trying to continue his studies. During the Civil War, he escaped by joining the Union Army, where he worked as a civilian nursing aid.

During his illustrious career, Allensworth served as a Captain’s steward and clerk in the Navy, a Baptist minister, and an educator, primarily in Tennessee and Kentucky. After his appointment to lieutenant, Allensworth was the second Black man in U.S. history to be promoted further to the position of Army Chaplain, at the time the highest rank a Black person could achieve in the armed forces.

In 1904, Allensworth settled in Los Angeles with his wife, Josephine Leavell, and two daughters. Biscoe says Colonel Allensworth was disillusioned by Los Angeles. “Because Los Angeles was so progressive, he thought it was going to be great,” she says. “But when he got to Los Angeles, he was truly disappointed, because racism was there, too. So he decided to find a place where he could gather his people and truly be free.”

Two years later, Allensworth retired from the army and traveled around the country lecturing on the need for Black self-sufficiency. One of his major goals at the time was to find a site in California where Black people could start a new life and build an independent community away from Jim Crow restrictions.

In his travels, Allensworth met Professor William Payne, African Methodist Episcopal minister Dr. William H. Peck, minister J.W. Palmer, and Los Angeles realtor Harry Mitchell, all of whom enthusiastically supported his plan to develop an all-Black town. Together, the men created the California Colonization and Home Promoting Association and acquired a tract of land in Tulare County. On August 3, 1908, the men founded the town of Solito, which they renamed after Allensworth just a few months later.

Visiting the park

On a 550-mile drive from the Bay Area to Las Vegas, I divert my route slightly to visit the park. The backroad farmlands offer a respite from the busy Central Valley highways, and at the tucked-away park I can stretch my legs, eat my picnic lunch, and explore California’s Black history.

State Park Interpreter Jerelyn Oliveira says most visitors find Allensworth through word-of-mouth, by driving by, or because of the park’s campground. Increasingly, people learn about the town through social media, navigation apps, and newspaper ads.

“We are off the beaten path, and, when they get here, people find out there’s a lot more to the park, and then they tell their friends,” Oliveira says. “That’s the best thing—they keep telling people.”

In a typical year, Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park holds four events in partnership with the Friends of Allensworth: Black History Month in February, Old Time Jubilee in May, Juneteenth in June, and Rededication in October. The events feature educational activities, musical performances, historical tours, arts and crafts vendors, speeches, and plenty of food. According to Biscoe, descendants of original Allensworth residents even make appearances at events and set up interactive storytelling booths. Because of COVID-19, the park had to cancel all events after March 2020, and they anticipate canceling Black History Month events in February 2021 as well.

But despite the current limitations, Oliveira says the park has been able to reach more visitors than ever thanks to virtual tour offerings provided by California State Parks. The on-demand programming, called Parks Online Resources for Teachers and Students (PORTS), allows visitors around the world to take a guided tour of Allensworth at their convenience.

The park is still open to the public every day from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Even though the park is not currently offering guided tours, guests can take a self-guided cell phone and signage tour on site. Visitors can even bring their bikes and cruise through the open streets. Because of the limited crowds, I am able to take my time meandering through the dozens of acres of downtown land and buildings, carefully reading each sign and listening to each story at my own pace.

“The Tuskegee of the West”

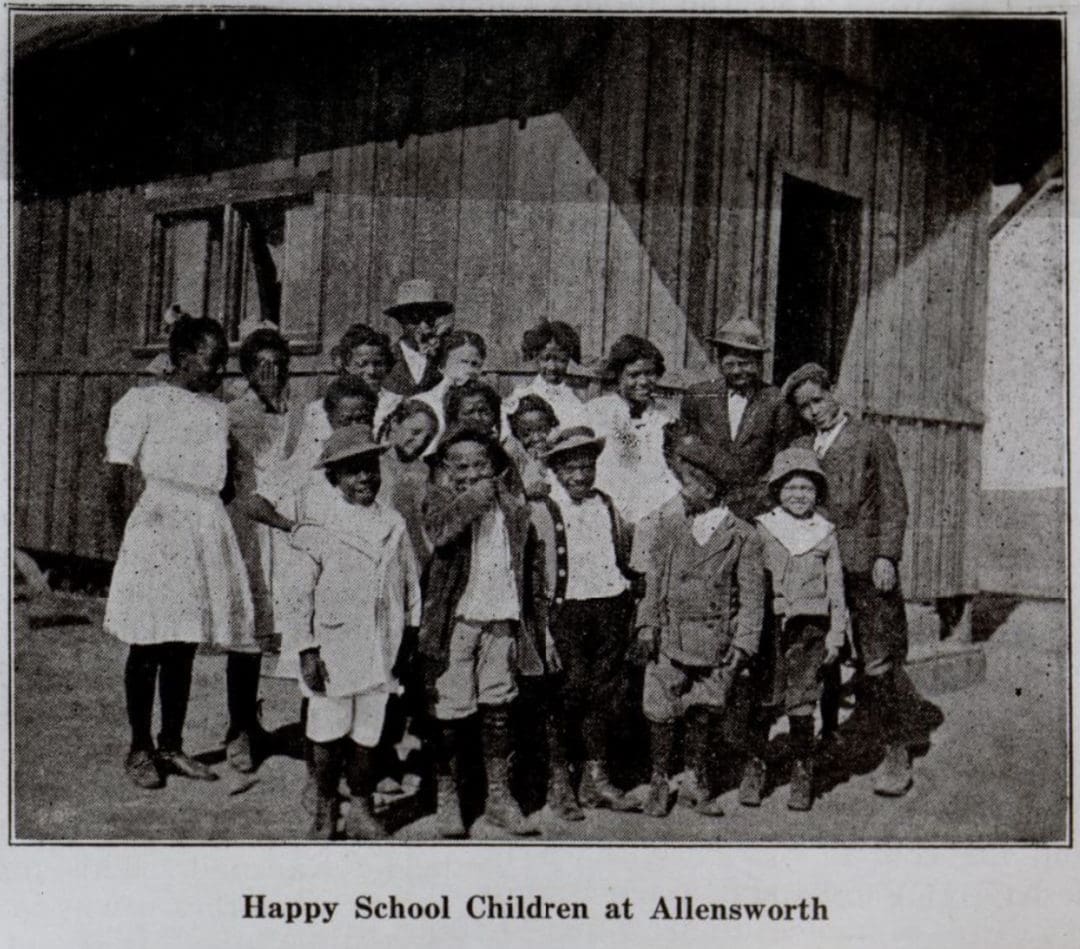

Education has always been at the heart of Allensworth. “There was a deep pride for education at a time when it wasn’t always necessary for kids to go to school,” Oliveira says. “People were willing to live in very difficult conditions to get their education.”

In 1912, the town of Allensworth established its own school district. At a construction cost of $5,000 (more than $100,000 today), the Allensworth School was the largest infrastructural investment in town. The one-room schoolhouse and library served elementary, intermediate, and high school students from a population of several hundred residents. Colonel Allensworth’s wife, Josephine, was the first teacher at the school.

“When the slaves were freed, oppressors took the chains off their ankles and wrapped them around their brains,” says Biscoe. “They were physically free, but restricted mentally. But when they came to Allensworth and other towns like Allensworth, that’s where there was true freedom. There was no Jim Crow, there was no discrimination, you could be whoever you wanted to be.”

Colonel Allensworth dreamed of turning the town into an educational hub and wanted to build “the Tuskegee [Institute] of the West,” Biscoe says. In 1914, he proposed the creation of a Black polytechnic school in town, based on the ideas of Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute. However, the idea was rejected by the state legislature, because, according to Biscoe, a school exclusively serving Black people was considered discriminatory under California law.

Following the rejection of the school, the town of Allensworth suffered two greater blows: The Colonel was killed when he was struck by a motorcycle while visiting Los Angeles in 1914, and in the 1920s, the Pacific Farming Company failed to deliver water to the town. Though the population of Allensworth steadily declined after these major losses, the Allensworth School House operated until 1973. That same year, California State Parks acquired the town and all of its buildings, intending to preserve them for educational and recreational purposes.

The Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park is, simply, about Black people’s lives, history, and humanity. The park’s story illuminates the life of Colonel Allensworth and all who supported his dreams of a self-sustaining, education-centric, discrimination-free society. After visiting the park, I’m left with a deep sense of awe and an incredible amount of hope.

Biscoe first visited Allensworth nearly 30 years ago; she had young children and wanted them to know their history, where Black people came from, and instill pride in them for what their ancestors had achieved.

“Everyone—especially African American children—needs to know their history,” she says. “If you grow up and you don’t think your ancestors contributed anything, and you don’t feel like you’re worth anything, that’s a problem. The first thing you need to do is educate a child about who he is and who his ancestors were and what they did, in order to make him realize, ‘If they can do it, I can do it too.’”

If you go

The Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park visitor center is open Monday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and the park is open Monday through Sunday 9 a.m. to sunset.