In the midst of the Southeast exists a perfect refuge from the daily stress of reality: Congaree National Park, a 41-square-mile patch of old-growth forest that defies the incessant hum of the interstate highways crisscrossing South Carolina. Dubbed the redwoods of the East—because some of its 130-foot-tall trees are related to the sequoias found in California—Congaree is the last stand of a forest ecosystem that was long ago cleared away to supply timber and to make room for farmland and development.

“The vast majority of the original forest has been destroyed, although we're talking about something that occurred over centuries,” says Greg Cunningham, a ranger at the park. “It wasn't until the 1950s or ‘60s that local folks realized they had something special you couldn’t find anymore.”

Today, Congaree is what’s left of a 30-to-50 million-acre forest that once stretched from Maryland to Florida, and as far west as Missouri. The timber industry was active in the area until the 1970s, when a coalition of conservation groups worked with South Carolina's U.S. Senators to get a national monument designation for the park. It was expanded, redesignated as a national park in 2003, and later as a UNESCO biosphere reserve.

Understated wilderness

I’m driving back east from California in the middle of November and doing my best to clear my mind. The East Coast—where trees obscure the long view, converting the sky into a beautiful sliver—isn't known for its uninterrupted wilderness. But when you start to consider the understated beauty of places like the Great Dismal Swamp—on the border between Virginia and North Carolina—or the Everglades, or even the great North Woods that cover New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine in a blanket of deep green, the eastern wilderness concept makes sense among its more postcard-worthy counterparts out west. There's a lushness that is at its best when you're up close and personal.

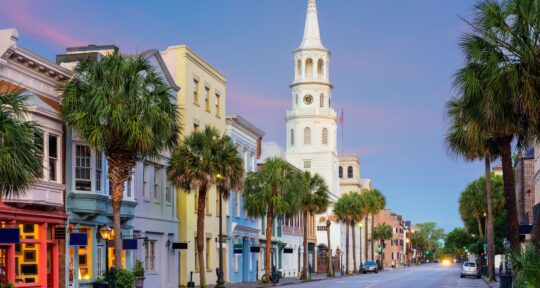

If understatement is a specialty, Congaree National Park has it in spades, beginning with the approach to the park. Leaving Charleston's growing sprawl, I drive for less than an hour on Interstate 26 before ending up on two-lane farm roads that hearken back to the days when more Americans lived in rural areas than in cities. Congaree sits roughly in the middle of a giant triangle formed by three busy interstates connecting Columbia (the state capital), Sumter, and Santee. The farther I travel from the rush hour-thickened asphalt ribbons of the city, the thinner traffic becomes.

Download the mobile app to plan on the go.

Share and plan trips with friends while discovering millions of places along your route.

Get the AppWithin 10 minutes, I’m driving past '50s ranch houses backed up against fields that, during growing season, are full of corn, peanuts, soybeans, and other crops. I occasionally pass the ruins of old wooden houses, their roofs caved in and nothing more than flecks of white paint still visible on their warped, weathered sidings. Despite this, the state's rural areas still feel alive and lived in. But the pace seems slower, too, and I feel the relaxation soothing my worried mind as I drive along the mostly-empty roads.

Canopy of trees

Other than a handful of signs posted here and there, you wouldn't know there’s a national park nestled amid these hundreds of acres of bucolic capital city hinterland. For a long time, not a lot of people did know. Cunningham, who has been a ranger at the park for the past five years, says that according to Park Service statistics, Congaree attracted fewer than 96,000 visitors annually 20 years ago. That number has crept up a bit—146,000 people found solace there in 2018—but it's a trickle compared with the millions of people that visit Yosemite National Park or the Great Smoky Mountains every year.

"For some reason, people are not familiar with the park or even this part of the state," Cunningham says. "A lot of people who come to South Carolina want to go down to Charleston or out to Myrtle Beach. The middle of the state is a lesser-known entity."

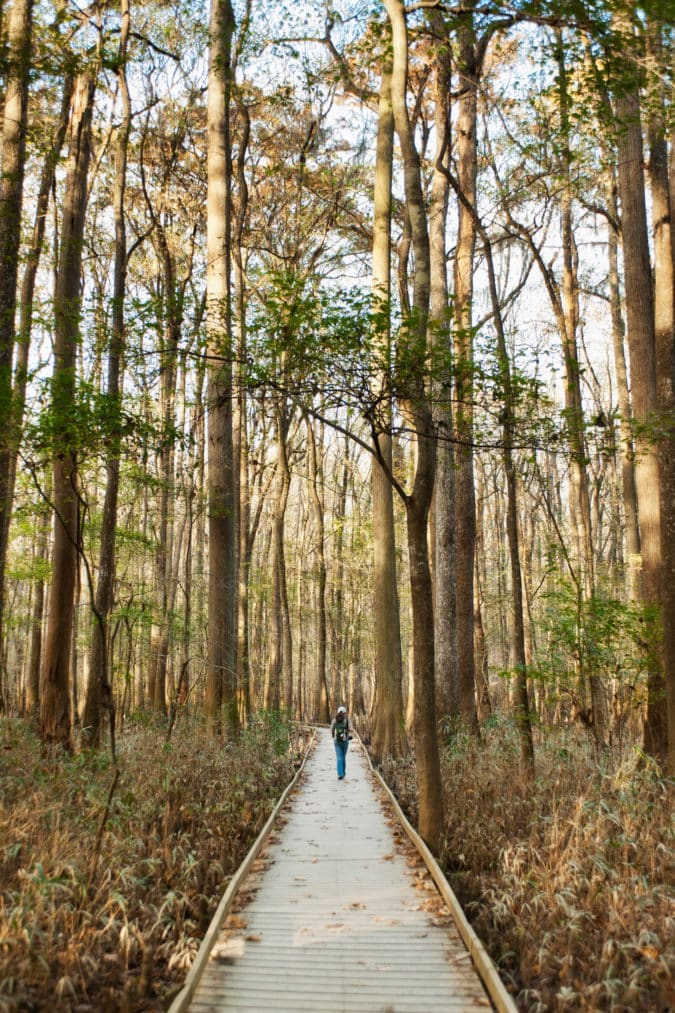

Those who do make it to Congaree National Park are in for a treat. The entry road winds toward the visitor center through a thick canopy of trees that offer only a taste of what's inside. More than 20 miles of trails and more than 10 miles of the Congaree River snake through the park. About 15,000 of its 27,000 acres are designated wilderness areas.

Some of the bald cypress trees—the ones related to the redwoods out west—have been here for centuries. The average canopy height is 130 feet, and among the tallest trees are a 167-foot-tall loblolly pine, a 157-foot-tall sweetgum, a 154-foot-tall cherrybark oak, and a 135-foot-tall American elm. The forest floor is teeming with wildlife—everything from bobcats, coyotes, armadillos, and otters to turtles, snakes, alligator gar, and catfish. It is also an important hub for migratory waterfowl. The river and its surrounding topography make the place what it is.

"Congaree is a floodplain forest, so it's a unique ecosystem most people aren't familiar with," says Cunningham. At any given time of the year, the forest floor could be dry, muddy, or flooded with a foot of water. Cunningham says that regardless of the season and how much water is among the trees, anytime is a good time to visit, because there are so many different ways to experience the park.

"All the different seasons and phases are beautiful, and we're open 24-7," he says.

A place to get away

On this warm November day, I’m enjoying an afternoon walk on the raised boardwalk that cuts a 2.4-mile loop around the north end of the park. There are several places to descend from the boardwalk onto solid ground, so I take off into the forest toward the river. Time slows down in the deep green light, and it’s quiet—except for the occasional rustle of a critter moving through the autumn leaves caught up in the undergrowth.

I watch the sun set over a large pond surrounded by trees and swamp grasses. Aside from the faint whisper of a jet flying high above, the sounds of mechanized progress have fled the place, leaving crickets, frogs, and other singing creatures an empty hall for their nightly concert.

One thing to keep in mind is that conditions can change from month to month and even from day to day. Cunningham suggests calling ahead to learn what conditions might be like before making the trip out. One day, you might need a pair of walking shoes; another, a kayak might be a better bet. There's a canoe and kayak access trail for the days when the river floods large parts of the forest. Two primitive campgrounds in the park cater to both individual campers and groups. Backcountry camping is also allowed, but it requires a free permit from the visitor center.

“Congaree is unique in the East,” Cunningham says. “You can go out and it's just you and nature. Even on a busy day, you don't have to go too far to get away from folks.”

If you go

Congaree National Park is open 24 hours a day, year round. The visitor center is open every day from 9 a.m to 5 p.m. and closed on federal holidays.