It’s 60 degrees in early January in Joshua Tree, California and the fiery cloud-speckled sunset foreshadows rain to come. There’s a post-apocalyptic vibe in the air; we’re a few weeks into a partial government shutdown and the namesake national park reflects a sense of chaos and calamity that writer and radio host Ken Layne describes as “an overnight collapse of any kind of basic social order.”

Anarchy already thrives in the desert, so Layne’s diagnosis is particularly unnerving. “It looks like we’re going to have to form local militias to protect America’s national parks from the federal government,” he comments wryly. But putting together a posse is going to wait—rabid listeners await his captivating commentary on the airwaves of KCDZ 107.7 FM every Friday at 10 p.m.

Layne is a New Orleans native who, despite having no formal education, had a successful journalism career at Gawker Media. Today, he’s known to Joshua Tree locals as the man behind Desert Oracle and Desert Oracle Radio, an independent publication and radio show-slash-podcast based in the sleepy (but quickly awakening) Mojave town.

Like many stubbornly self-reliant desert folks living on the fringes of society, Layne is a one-man show.

“I write, edit, design the books, do the mail order and retail deliveries/shipments, clean the office (sometimes), go to the bank and the post office, pay taxes, do the accounting, produce and host the radio show, distribute the podcast, etc.,” Layne says as we correspond over email. On top of that, he occasionally makes appearances at places like the Ace Hotel in Palm Springs to host “Campfire Stories,” which he describes as being “like an old park ranger at the campfire circle, telling stories of ghosts and rattlesnakes and UFOs and serial killers.” (The next one is on Thursday, January 31 from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m. and, like all Campfire Stories, it’s free and open to the public.)

It’s no accident Layne’s based on the edge of civilization. Desolate landscapes are magnets for escapism and artistic impression. You don’t have to look far to find fringe installations like Salvation Mountain in the low desert of Imperial County, California, and Seven Magic Mountains in Ivanpah Valley outside Las Vegas. Creative vision without the baggage of cultural influence has lead geniuses to life-changing revelations—or, on the flip side, ultimately succumbing to madness.

Joshua Tree is no exception. The desert town is home to everything from doomsday cults to UFO clubs to the Integratron—a “resonant tabernacle and energy machine sited on a powerful geomagnetic vortex,” according to its website. Time travel, alien communication—anything goes. And Layne has long been obsessed with the macabre, the cataclysmic, the weird. He’s of the world, but not in the world so to speak.

“I like being as far away as possible, not least because I have a gloomy belief that things are hanging by a thread. Of course whenever things seem to be falling apart somewhere, I try to get a publication to send me there to cover it, because I love covering riots and social movements,” says Layne.

“WHENEVER THINGS SEEM TO BE FALLING APART SOMEWHERE, I TRY TO GET A PUBLICATION TO SEND ME THERE TO COVER IT.”

But finding his fit took time. True to his oracle sobriquet, Layne foresaw the sea change of how people interact with the Internet. In 2014, he left Gawker and traveled for a year on a quest of self-discovery.

“I spent that year wandering, thinking, staying in remote Buddhist and Catholic monasteries, solo hiking, all-night drives, that sort of thing,” explains Layne. But the desert’s siren call stayed with him. He reminisces about his prolonged odyssey to the dusty little enclave known for yucca brevifolia and a U2 album.

“Decades ago, when I was first exploring the Mojave in my 1972 International Scout, the PVC valve blew out driving up Cima Dome and oil was leaking and burning and it was 5 a.m. on a wintertime weekday. [I] made it to Baker on the 15 and waited for the garage there to open for the day. Mechanic showed up just before sunrise and went to work on the Scout, and I walked around the back of the shop, watching the sun slowly light up all these jagged mountains. Other than a semi-truck going by now and then, it was very quiet and the air was so cold and clean. Right then I decided that one day I would live in a very small desert town and have these golden mountains all around, every day. It took a couple of decades but eventually it worked out.”

Nowadays, it’s hard to think of Joshua Tree as “very small.” It’s true that some desert neighbors are miles apart from one another. But Layne laments that that’s changing.

“I’d rather be in a quieter, lonelier place than 2019 Joshua Tree, with its tourist mobs and traffic jams,” he quips. “Maybe it will quiet down again, after the next economic or political collapse. It slowed way down after the 2008 recession. Maybe it will get too hot to live here year-round, like these past couple of summers. It’s getting hotter and more humid every summer, and the winters are getting milder. Everything’s blooming right now, and this started in mid-December. The plants are confused.”

Even climate change hasn’t stanched the increasing popularity of J-Tree. When the tourists flocking to see Paul McCartney at legendary saloon Pappy & Harriet’s in nearby Pioneertown get to be too much for Layne, he hits the road.

“I just like to get on the road, listen to satellite radio, stop and take a walk whenever it looks interesting and the weather is bearable,” says Layne. “Route 66 through Mojave Trails National Monument is always a great drive. When it’s cool enough, there are endless places to explore along the way: Amboy Crater, Roy’s Cafe, all those little ghost towns with a decaying gas station and bottle shop, freight trains rumbling by. The 395 through Owens Valley is my favorite part of the world, between Mt. Whitney and Death Valley and Mono Lake.”

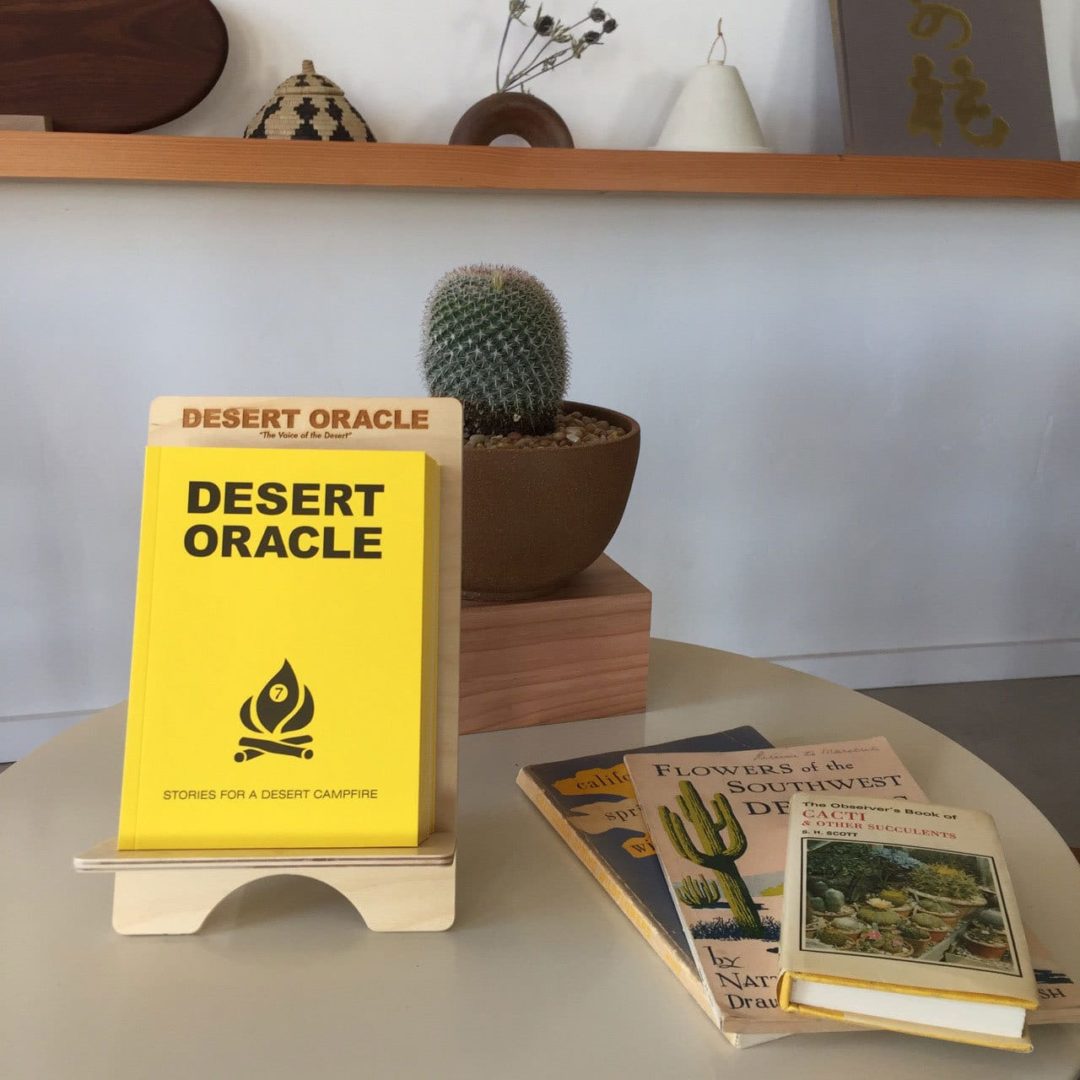

The vast desolation that deserts inspire are the perfect fodder for Desert Oracle. No subject is too fringe to explore. Aesthetically, the magazine is stylized after mid-century field guides with an emphasis on “strange tales, singing sand dunes, sagebrush trails, artists and aliens, authors and oddballs, ghost towns and modern legends, musicians and mystics, scorpions and saguaros,” according to the Desert Oracle website.

Articles range from dissecting an alien hostage-taking conspiracy theory from the 1960s (Issue #6: “Legends of the Aliens: The Krill Papers”) to a profile of the legendary Yucca Man, the Mojave’s answer to Bigfoot, in Issue 4’s “The Known Unknown: Tales of Desert Sasquatch.” Each issue also always contains an eccentric desert-humor column by Godfrey “Doc” Daniels based out of Show Low, Arizona.

Layne lists a few of his favorites stories from over the years.

“The weird lines connecting ritual magicians like A. Crowley with the Mojave Desert and cults and the space program are a bottomless well. I’m always pulling up more parts to that story, and readers send me every kind of spooky story. The links between UFO lore and petroglyphs and Edwards AFB/China Lake/Area 51 are always interesting to explore. Desert characters in general—murderers, miners, land speculators, religious nuts, military figures, famous and not-so-famous artists and con-artists—make for good campfire stories or radio shows.”

Right now, the magazine has 3,000 subscribers, despite its sporadic publishing schedule. Only seven issues have been published thus far with an eighth anticipated at the end of January 2019. Copies of the bright yellow and black mid-century inspired modern guidebooks can also be found in a smattering of local (or semi-local) shops, generally within a close proximity to Joshua Tree in order for the fullness of its power to be realized in its natural habitat.

Layne’s radio show isn’t exactly a late-night lullaby (“Monsters of the Mojave” is a recurring theme), but it’s scarily addictive. His cult following tends get lost in his easy drawl for hours before they snap out of it and realize they’ve gone off the deep end of a thousand government conspiracy theories.

“THE CURE FOR EVERYTHING IS TO GET ON THE ROAD AND DRIVE AROUND THE DESERTS.”

But Layne’s burgeoning success may be considered a double-edged sword. There’s a delicate symbiosis required for those coexisting with the desert; the more popular an off-the-grid retreat becomes, the more it stands to evolve (perhaps detrimentally) from outside influence. He hopes that rather than destroy the pristine beauty of national parks, increased attention will instead raise awareness of the fragility of these iconic—and threatened—ecosystems. But he admits it’s a bit of a long shot.

“Because of the crooks running the Interior Department right now, all federal land is at risk. It’s been there for a century-plus now, national parks and monuments and millions of acres of Bureau of Land Management land, but when a country’s political system breaks down you can’t assume anything will survive the catastrophe. But you have to try.”

Sometimes when the trying gets tough, Layne finds it’s easier to cleanse his mind and spirit by getting a fresh outlook. His remedy for the weary?

“The cure for everything is to get on the road and drive around the deserts.”