I’m strolling along Main Street in Erwin, Tennessee, as the sun flares behind the mountains to the west. It looks like any ordinary downtown: brick buildings from the dawn of the train era; an antique store and a shoe repair and saddle shop; a handful of bright, sleek cafes that I’d seen advertised on the Appalachian Trail, which skirts the town. Fast food restaurants glitter past the railroad tracks down by the interstate and vending machines sell Dr. Enuf, a soda popular in this part of the country.

But I’ve come to this street in search of what distinguishes Erwin from its neighbors: a collection of elephant statues, shellacked and painted in an array of dazzling colors, that appear in the town’s business district every summer. If you saw these elephants without context, you might not realize that these adorable, doe-eyed statues were conceived as a positive twist on a dark chapter of Erwin’s history.

A little more than a century ago, back in the days of the traveling circus, Erwin hanged an elephant.

In 1916, the circus came to town. During a parade in neighboring Kingsport, an elephant named Mary threw, trampled, and ultimately killed her trainer in front of a horrified crowd. The townspeople demanded vengeance, Amy Louise Wood writes in an article titled “Killing the Elephant: Murderous Beasts and the Thrill of Retribution.” Using a rail yard crane in neighboring Erwin—since Kingsport didn’t have one tall enough—they hoisted Mary up and hanged her. A photograph of this macabre execution shows a ghostly, improbable shape choking on a rope, four huge feet dangling above the ground.

In the intervening century, this incident became a stain on Erwin’s collective soul.

“It was a black eye for everyone,” says Jamie Rice, president of RISE Erwin, a group of young professionals seeking to improve life in Erwin and surrounding Unicoi County. “All the locals, we used to hate it when people would come into town and ask us, ‘Were you really the town that hanged the elephant?’ No one wanted to talk about it.”

Turning tragedy into art

A few years ago, with the centennial of Mary’s death looming, Rice and her compatriots decided that they’d had enough. Things were bad enough in the town as it was: In 2015, rail-based freight transportation company CSX closed its Erwin rail yard, which had been the town’s main employer (and the place where Mary was hanged a century prior). On top of that, the town was experiencing other problems facing rural America, chief among them the opioid crisis. What if, thought Rice, they reframed the story of Mary’s death?

“Our group decided, we’re not going to bury our heads anymore, we’re going to bring it into the light and talk about it and make it positive,” she says.

The group decided to commission a series of fiberglass elephant statues, decorated by local artisans, and place them at various spots on Main Street over the summer. “We knew that public art was a great way to bring people together, to get more foot traffic downtown,” says Rice.

At the end of the season, the town auctioned off the statues and donated all the money to an elephant sanctuary outside Nashville, which is where, Rice points out, an elephant like Mary would be sent today. The first auction raised about $12,000 for the sanctuary. “It was like a new page had been turned for the town,” Rice says.

Erwin exhibited and auctioned another set of elephants the following year, and the tradition kept going. The first few years, the town donated all the money to the sanctuary; these days, they invite bidders to sponsor each elephant and choose a charity for the proceeds, although they still earmark 15 percent of all profits for Mary’s brethren outside of Nashville.

A reason to smile

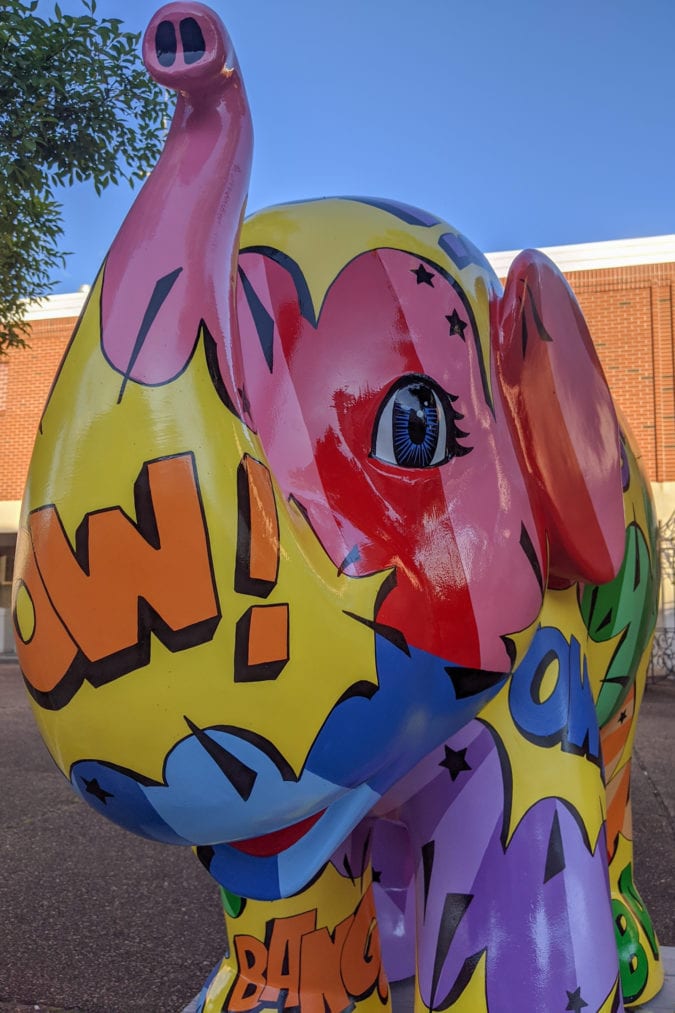

When I take a tour of the elephants, I start in front of Erwin’s municipal office, where I see a dopey-faced elephant painted in colors that call to mind the nearby mountains. Next stop is an elephant in front of a gunsmith, painted with bees, honeycombs, and a riotous pink tree. On the west side of the street, an elephant christened “Doll-E” is painted with geometric shapes and eye makeup; a butterfly is perched on its trunk.

Some years, the elephants are painted with local scenes, such as the nearby Nolichucky River and the Appalachian Trail, but this year’s follow a pop culture theme. I see a Star Wars elephant, a candy-colored elephant painted with the words “WOW,” “ZAP,” and “BANG,” and an elephant festooned with Dr. Seuss characters. A University of Tennessee football elephant guards a shuttered moviehouse. I feel as if I’m on a scavenger hunt, peeking ahead to the next block to see if I can spot a trunk in front of a pharmacy or karate studio.

I finish my journey at a rainbow-painted elephant guarding the southern end of the street, raising its trunk proudly against the faded sky. As I stroll back through the business district, admiring the herd, I notice that I’m not the only one who is out and happy to see the elephants. Families lead their children from statue to statue, kids swing on the trunks, and people stop to snap photos. The mood is convivial and lively; it’s easy to see that these elephants bring plenty of joy—which is exactly what RISE Erwin intended.

“We figured out we need to make our own good news,” says Rice. “We thought, let’s change the perception of who we are and why you’d want to come to Erwin and live and raise your family and start a business. We need a reason to smile.”

If you go

This year’s elephant statues are on display along Main Street in Erwin, Tennessee, until December 1, 2020.