I first learned the tragic story of Emmett Till during history class. The 14-year-old boy arrived in Mississippi from Chicago in the summer of 1955 to visit relatives, not used to life in the South under Jim Crow. On August 24, 1955, he skipped church with his cousin and visited Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market in Greenwood to buy candy. Exactly what happened next is unclear, but Till was accused of whistling at Carolyn Bryant, the 21-year-old wife of the store’s owner, Roy. A few days later, Roy and his half-brother allegedly kidnapped, tortured, and murdered Till; in September, they were found not guilty by an all-white jury.

When I moved to Mississippi, the legacy of Till and the subsequent civil rights movement became a part of my everyday life. In 2008, a sign was installed marking the spot where Till’s body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River just outside of Glendora. Several signs were stolen, thrown into the river, and shot up with bullet holes before a fourth sign—made of bulletproof steel and weighing more than 500 pounds—was installed in 2019.

The Emmett Till Historic Intrepid Center (E.T.H.I.C.), also located in Glendora, is about a 2.5-hour drive from where I live in Tupelo. The journey through the Mississippi Delta along Highway 32 is filled with pine trees and empty fields—now a testament to the brutality of slavery and displacement of Native Americans during the Trail of Tears. I pass through once-thriving towns decimated after white residents left and took their wealth with them. As of 2017, the population of Glendora was 151.

The healing starts here

Glendora’s mayor and E.T.H.I.C. director Johnny B. Thomas greets me from behind his desk. His small office is decorated with letters from leaders such as Mississippi Representative Bennie G. Thompson and tickets from both of President Obama’s inaugurations. His desk contains pamphlets for the Mississippi Blues Trail, as well as copies of the book he wrote about Glendora’s history, A Stone of Hope.

In 2005, 50 years after Till’s brutal death, Thomas founded E.T.H.I.C., the first and only museum dedicated to Till. When I ask Thomas why he founded the museum, he repeats a phrase: “The healing starts here.” But the last 15 years haven’t been easy. “We’ve not really received a lot of funding,” Thomas says. “Our effort to maintain this place has basically been through the community. We have no wealth, but we have a wealth of history.”

Visitors to E.T.H.I.C. have the option of watching an introductory video where witnesses recount their memories of the events that unfolded during the summer of 1955. The video also explains that the museum was created as an effort to right historic wrongs, with a focus on the human rights violations that occurred because of slavery and the Jim Crow era.

According to the museum’s website, its mission is “to provide a penetrable, thought-provoking, and educational experience to preserve and promote the historical and cultural heritage of the Town of Glendora, Tallahatchie County, and the State of Mississippi in the continued struggle against civil and human wrongs.”

Somber lighting forces me to look only at the items right in front of me. An exhibit on Glendora’s history explains that across most of the Mississippi Delta, formerly enslaved people worked as sharecroppers and lived under the duress of Jim Crow for almost 100 years. Farming tools, reproductions of segregation signage, and a life-size painting of Till and his mother bring the past into the present and send chills through my body.

A timeline documents the painful progress of the civil rights movement, and a replica of Bryant’s grocery stands nearby. There’s a historical marker outside the original structure, which is currently in ruins; the state of Mississippi has ignored pleas to preserve it.

Death and life

It’s not easy to get to Glendora, but despite its remote location, the museum sees visitors from all over the world. The Mississippi Delta is also the home of the blues, and E.T.H.I.C. features guitars, records, and other memorabilia from Sonny Boy Williamson II, who was born in Glendora. “[Williamson] is the king of the harmonica,” Thomas says.

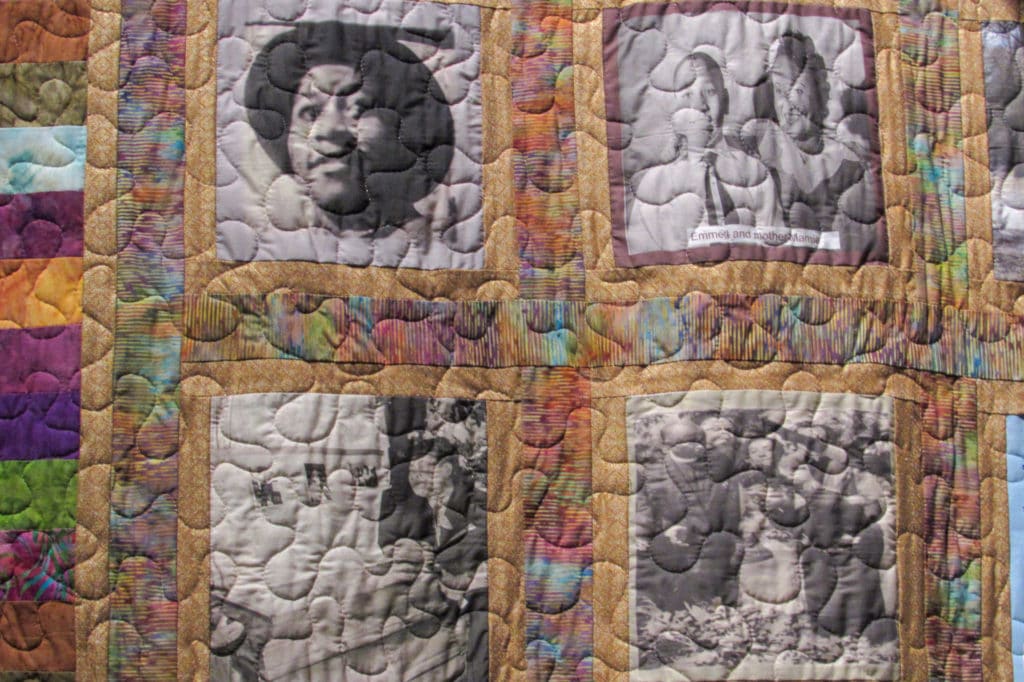

E.T.H.I.C. isn’t just about preserving the memory of Emmett Till’s death, the museum also celebrates his life. A reproduction of the room he stayed in during his visit to Mississippi and a quilt made in his honor are displayed near a facsimile of the car that was used to transport him during his abduction. A candle-lit vigil is held every August 28 to honor the memory of Till, and the Shirley Thomas Center (named for Thomas’ late wife) hosts community events throughout the year.

Thomas says he considers the museum to be a “living thing” and has big dreams for the space. In the future, Thomas would also love to see the area designated as a national monument. “We’re hoping to continue to grow,” he says. “I won’t allow it to die. I hope this community never allows it to die.”

If you go

The Emmett Till Historic Intrepid Center is open Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m to 5 p.m, Saturday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., and closed on Sunday. It’s open by appointment only on Monday.