More than a century before the global COVID-19 pandemic brought travel to a screeching halt, another respiratory disease put a small town in upstate New York on the map. The condition was tuberculosis and the town Saranac Lake, located in the Adirondacks, less than a two-hour drive from the Canadian border.

Before tubercular patients descended on the village during the second half of the 19th century looking for a cure, Saranac Lake and the surrounding area was a popular spot for outdoor enthusiasts. “The area was really a destination for people who were seeking recreation—visiting as tourists in the wilderness before people were coming as health seekers,” says Amy Catania, executive director of Historic Saranac Lake.

This meant that until antibiotics became the standard treatment for tuberculosis in the 1950s, Saranac Lake warmly welcomed both outdoor enthusiasts and those who sought a cure for the disease.

From the great camps to chasing the cure

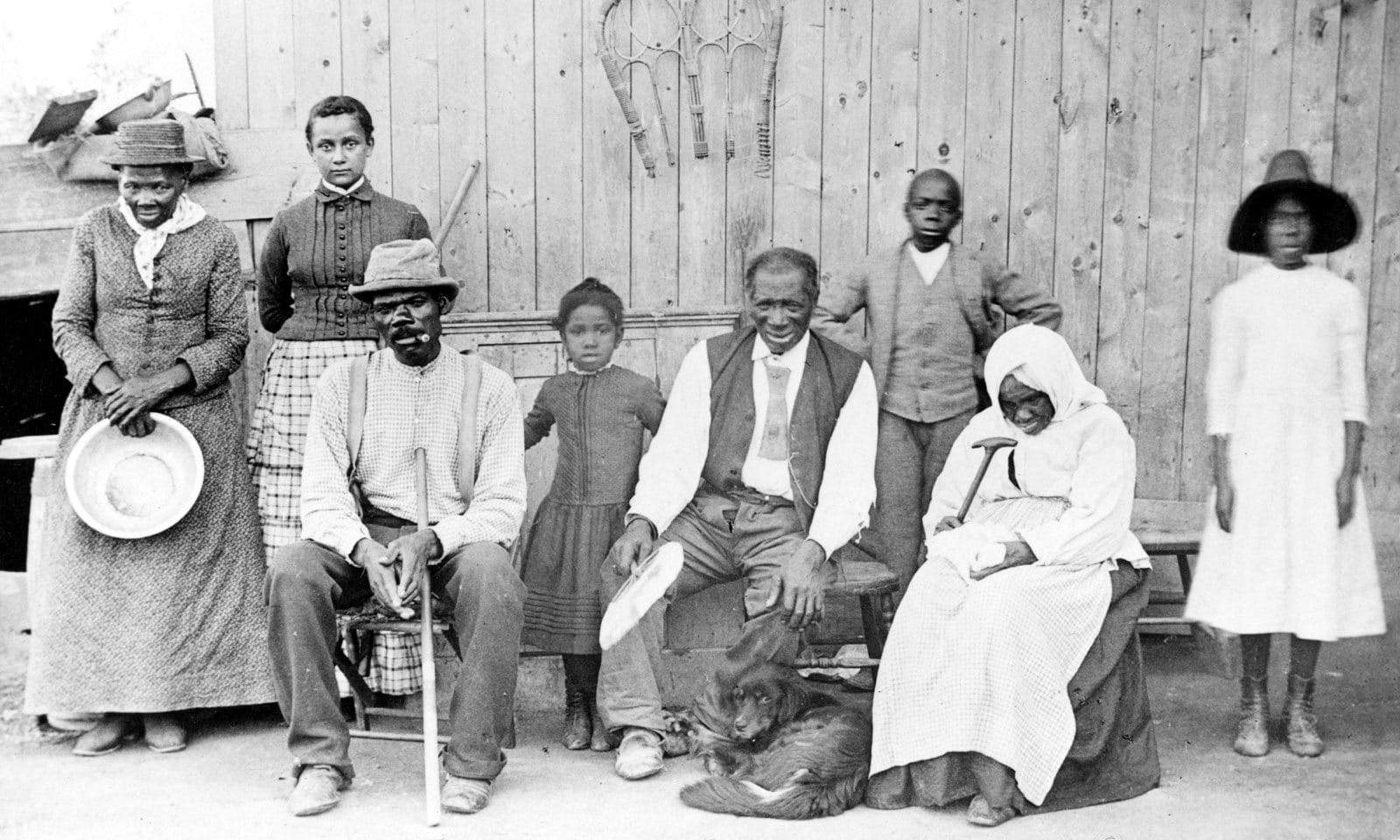

Prior to the arrival of white settlers, Native Americans used the Adirondacks for hunting and trapping. Word spread about this lush region of the state, and by the early 1800s, the Saranac Lake area became a vacation destination for wealthy men from New York City who wanted to hunt, fish, and participate in other wilderness activities. To accomodate this influx, various forms of lodging started popping up in the mid-1800s, including Paul Smith’s Hotel, which opened in 1859. Some of its most well-known guests included Theodore Roosevelt and P.T. Barnum.

Among the outdoorsmen drawn to Saranac Lake was Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, a physician from New York City who was suffering from tuberculosis. He had visited the area’s wilderness camps previously to hunt and fish, and returned several years later in 1873 after he fell ill, hoping that the fresh mountain air would help cure him. Trudeau did, in fact, regain his health and ended up relocating his home and medical practice to Saranac Lake in 1876.

At the same time, many of the richest families in New York City began purchasing lavish country retreats in the Adirondacks, often referred to as Great Camps. But tuberculosis did not discriminate based on class, and when members of these wealthy families fell ill with the disease, they escaped to their Great Camps to heal. According to Catania, Trudeau treated these well-to-do tubercular patients during the summers they spent on the lakes.

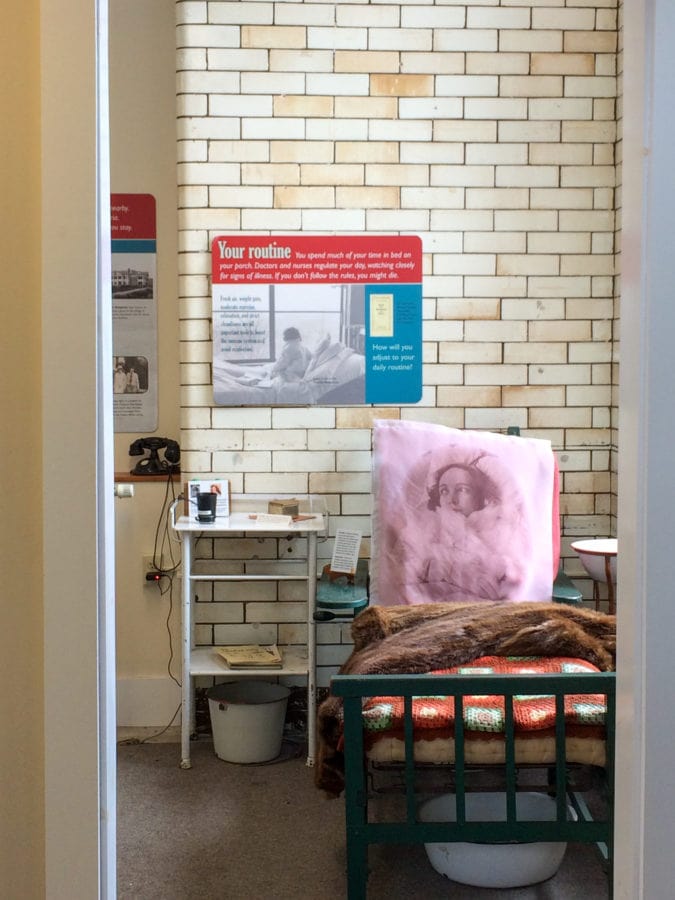

A few years later, in 1884, when Trudeau established the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium (later renamed the Trudeau Sanatorium), some of these families returned the favor and became early funders of his facility. His first patients were two sisters from New York City who had been factory workers before falling ill with tuberculosis. They were treated in a one-room cottage called Little Red, which is still standing today. And though the sanatorium quickly grew in capacity, there were always more patients than rooms.

“People were trying to get into Trudeau’s sanatorium, which was never big enough to accommodate everybody,” Catania says. “So they were also staying in the local homes, in camps, and other sanatoria that grew up in the area.” It didn’t take long for Saranac Lake to become one of the most popular destinations for tubercular patients in the country.

Navigating tuberculosis and tourism

By the 1920s, Saranac Lake had transformed into a successful health resort—but it was also stigmatized due to the large number of people with tuberculosis living in or visiting the town. Catania once interviewed a woman who grew up going to one of the nearby Great Camps. During the interview, the woman shared that as she and her family were on the train from New York, her mother would tell them to cover their mouths with a handkerchief as they were passing through Saranac Lake. Along the same lines, some wealthy families and individuals who owned Great Camps rarely came into town. “If they did come into town for some reason, and they had to eat somewhere in the village, they would bring in their own silverware, because they were so afraid of the germs,” Catania says.

To help keep residents safe and ease the minds of visitors, Saranac Lake was an early adopter of public health measures, like outlawing spitting on the sidewalks. “People had to use sputum cups with liners that they would spit into,” Catania explains. “The health society would come around every night and collect the sputum out of these liners and burn them. That was part of the system for keeping everything in the town clean.”

Even with the wealthy avoiding Saranac Lake, the town still had a booming economy during the Roaring ‘20s, thanks to the influx of people with tuberculosis who continued to come for treatment and recovery. At this point, Catania says, local residents decided that it might be beneficial to branch out to other types of tourists. This strategy included opening a number of hotels, most notably the Hotel Saranac, which opened in 1927 and is the only one still standing today.

Unlike other accommodations in the area that ended up burning down, the Hotel Saranac was built of brick. “They really marketed themselves as a city hotel, and also a hotel that was built of steel and concrete so it was fireproof,” says David Roedel, development officer for the Roedel Companies, which owns the Hotel Saranac. The hotel was strategically located on Main Street in the center of downtown, within walking distance of the train station. Though this made sense initially, once automobiles became the more common mode of transportation, the hotel lost guests to motels and other lodging outside of the town’s center.

No sick people allowed

The first advertisement for Hotel Saranac describes the property as “modern, fireproof, 100 rooms, 100 baths, no invalids, European plan.” While the fireproof construction and bathrooms attached to each guest room were certainly draws, what sticks out today is the specification that “no invalids” were permitted to stay at the hotel.

“I think the Hotel Saranac was trying to carve out a different market in the village,” Catania says. “A lot of people were coming to Saranac Lake who weren’t sick themselves. They were family members of sick people, merchants, or people who were supplying goods to the different businesses in town that were catering to patients. The idea was to open rooms so that people who weren’t sick would feel comfortable staying there.”

Beyond that, the Hotel Saranac was designed as a modern, urban hotel like you’d find in any major city in the United States, but located in a small town in the Adirondacks. “It had all these modern amenities—like the 100 baths for 100 rooms—that were very foreign at the time,” Roedel says. Given the hotel’s prime location in the center of the downtown area, the first floor housed around 25 small businesses—including a dress shop, flower shop, pharmacy, barber shop, coffee shop, and soda fountain—that catered to both locals and travelers.

Though the Hotel Saranac’s first floor had an array of shops, its registration desk was located on the second floor of the building. According to local lore, this was done as a precaution, “because they wanted to keep the registration away from the street level and away from the ‘disease,’” Roedel says. “And so the hotel guests would register on the second floor and then go to their rooms, which I think was a unique aspect of the hotel.” The hotel’s ballroom and Great Hall were also located on the second floor for the same reason: It allowed guests to feel as though they were separated and safe from the tubercular patients the town was known for.

“The idea was to open rooms so that people who weren’t sick would feel comfortable staying there.”

The Hotel Saranac is a great example of a new type of city hotel from the period that catered to the middle class. Though they had relatively small rooms that were available at a reasonable price, the hotels also featured grand ballrooms and other public spaces that gave guests the experience of staying at a high-end property. The Great Hall on the second floor was modeled after the 14th-century Davanzati Palazzo in Florence, Italy, and features intricate woodwork and artwork which have been restored in painstaking detail.

Saranac today

Despite the initial “no invalids” policy, the Hotel Saranac and tuberculosis are inextricably linked. The hotel was designed by architects William H. Scopes and Maurice Feustmann, two of Trudeau’s former tubercular patients who came to Saranac Lake to cure. Scopes and Feustmann specialized in designing sanatoria, hospitals, and Great Camps, and are responsible for some of the larger buildings in Saranac Lake, especially near the Trudeau Sanatorium.

Saranac Lake’s proximity to Canada—and therefore, bootlegged alcohol—made it a popular party destination during the 1920s. In fact, the Hotel Saranac was rumored to have a speakeasy in the basement, though Roedel says that no definitive space was uncovered during the restoration process.

After the stock market crash of 1929, fewer people were able to travel for leisure. “Once the Depression hit, although the [tuberculosis] industry continued in Saranac Lake, there wasn’t the same kind of tourism going on,” Catania says. Despite being booked solid for five months during the 1932 Winter Olympics in nearby Lake Placid, the Hotel Saranac was never financially successful. It changed hands many times over the years and eventually fell into disrepair. The Roedel Companies purchased the property in 2013, and after several years of extensive, historically accurate restoration, the Hotel Saranac reopened in January of 2018 and has been welcoming guests back ever since.

I had a chance to stay at the hotel shortly after it reopened and enjoyed spending time wandering through the narrow hallways and exploring the opulent Great Hall and ballroom on the second floor. Even before I knew about the hotel’s history, I found myself gravitating toward the common spaces on the second floor—just as the architects had intended. Though the registration desk is now located on the first floor as you walk in, the original concept of the arcade has been brought back in the form of Academy & Main, a curated collection of community-made goods. On the opposite side of the original arcade, the Campfire Adirondack Grill + Bar serves as a restaurant for both locals and hotel guests, much like the building’s original coffee shop and soda fountain.

Today, Saranac Lake is a destination in itself, while also being a hub for outdoor activities in the Adirondacks. Visitors can learn about the local history at the Saranac Laboratory Museum, which is located on the same block as the Hotel Saranac.

Though the hotel is temporarily closed because of the COVID-19 outbreak, Roedel hopes that the fresh air and natural scenery will once again draw people to the area when we resume traveling. He says, “I wonder now, as we get out of this hell, if people are going to go to places like the Adirondacks to escape, after being stuck in their apartment or house for so long, and longing to enjoy nature again.”