The Forney Museum of Transportation is located in an industrial chunk of north Denver dominated by highways, forgotten factories, and a short stretch of the South Platte River. This is RiNo, the River North Art District, one of Denver’s gritty, hip areas.

I visit with my friend Paul Parker. We find the nondescript, low building on RiNo’s northern edge, past the Butcher Block Cafe, a giant Pepsi bottling plant, and the Euflora 3D Cannabis Center. The museum is sandwiched between I-70, the Denver Coliseum, and an old set of railroad tracks—an appropriately concrete-covered site for a museum dedicated to wheeled vehicles. It is also a location that speaks directly to Denver’s longtime role as the crossroads for an entire continent.

Roadside icon

Paul, 53, grew up in Colorado. He last came here 40 years before, on a school trip, when the museum was still in its old location in the Denver Tramway Powerhouse building. That’s where J.D. Forney and family, for 30 years, displayed their curious, vast, ever-growing collection of vintage cars, motorcycles, bicycles, and trains.

Paul remembers the old building as “a cavernous, dusty place” with light streaming in through high windows and an outdoor yard for the bigger trains and extra vehicles. The entire collection is indoors now and we’ve come mainly to see the special exhibit called “Home is wherever you park: Vintage Camping Trailers.”

More than anything, Paul remembers how easy it was to slip away from his class and explore the place on his own. On this afternoon, Paul has slipped away again, and so have I, both of us taking a few hours off from our otherwise busy lives, just to geek out on shiny cars and Airstreams.

The Forney Museum moved to its current location in a giant warehouse on Brighton Boulevard in 1999, a feat which included transporting the collection’s prized possession—a 1.2 million-pound Big Boy steam locomotive—across the city. Only 25 of the behemoth Big Boy locomotives were ever built and only eight still exist. These were the engines that pulled trains over the otherwise impassable Rocky Mountains. The one at the Forney is the Union Pacific Big Boy #4005; its image graces the walls of the gift shop and a rack of t-shirts.

Right on cue, as we’re standing in line to pay our $12 entrance fee, an excited train fanatic in front of us asks, “Is there really a Big Boy here?”

“Oh, you can’t miss it!” the ticket seller responds.

Geeking out

Instead of going straight to the main attractions, Paul and I step into a room dedicated to antique matchbox cars and models. It’s a detailed, miniature prelude for what’s to come. The walls and center of the room are lined with glass cases, all filled with rows of brightly painted toys, like jewels.

We join several visitors in a quiet, walking meditation around the room, slowly stepping and inspecting, hands clasped behind our backs. Small, printed-out strips of paper are glued beneath each of the models with details like: “The 1949 Cadillac had the first hardtop convertible body style, the first modern V8 engine, and the first tail fins.”

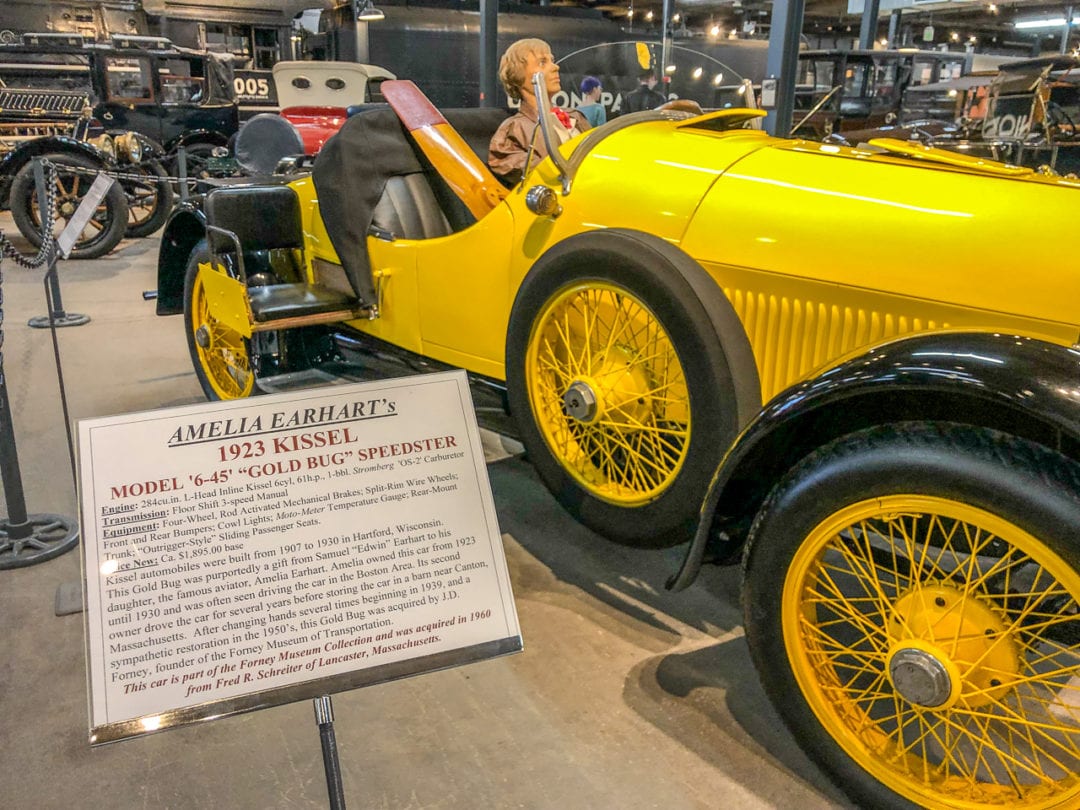

Finally, we’re ready to go big. We step up to the secure door next to the ticket desk and wait to be buzzed into the 70,000 square foot hangar space. The Forney collection began over 60 years ago when J. D. Forney, an inventor and businessman in Fort Collins acquired Amelia Earhart’s 1923 Kissel touring car—by trading his 1919 Model T Coupe for it. This car, which started it all—a long, bright yellow “Gold Bug” convertible, driven by a mannequin Earhart—greets us as we enter the main museum.

Forney had patented a soldering system, the Forney Arc Welder, and started the Forney Manufacturing Company, a welding and metalworking company going strong today. His vehicle collection grew as he bought—or traded welding equipment for—antique cars, vintage buggies, early-model motorcycles, steam locomotives, aircraft, fire engines, street cars, sleighs, bicycles, and toys. Today, in addition to the Big Boy, the collection’s top items include a Denver & Rio Grande Dining Car, Colorado & Southern Caboose, a 1923 Hispano-Suiza luxury car, Indian motorcycles from 1913 to 1953, a Stutz Fire Engine, an 1888 Denver Cable Car, a 1923 Case Steam Tractor, and an 1817 Draisienne bicycle.

Like traveling back in time

As Paul and I walk the aisles between carefully placed clusters of vehicles, we find ourselves wandering in and out of decades and centuries. One minute we were among cars from the 1920s or 1950s; the next minute, we cross the aisle and are looking wax figures of Buffalo Bill and Sitting Bull in the eye as they stand in front of a covered wagon, advertising their show. There are other historical wax and mannequin figures throughout the museum, including Dwight Eisenhower in a small military equipment display and the Wright Brothers in their bicycle workshop.

The place isn’t as dusty as Paul remembers it, and I find the whole operation strikingly well-organized and efficient with space. The Forney is about as old-school and non-tech as a museum can get. There is one audio clip about Big Boy #4005’s history, which is triggered by a button; and you can climb into the engine cab to see all the dials and levers—but that’s about as interactive as it gets here. The only other hands-on opportunities are being able to climb behind the wheel of a 1915 Model T for a photo op in front of a painting of an open road; and you can sit in a historic chair from the Colorado Midland Railroad, founded in 1883. They built the first standard gauge railroad over the Continental Divide, over Hagerman Pass.

Otherwise, the experience is walking, admiring, talking, and pointing. After a quick sit in the train chair, we carry on with all of the above.

“Keep right on going”

We’ve taken our time getting there, but finally, like moths to a flame, we find ourselves in front of a dozen or so polished, gleaming vintage campers. They are arranged into little scenes of travel and repose, complete with patches of astroturf and charcoal grills.

In his book Under the Stars: How America Fell in Love with Camping, author Dan White begins his chapter on RVs and mobile homes with a 1959 quote from Wally Byam, founder of Airstream: “Don’t stop. Keep right on going. Hitch up your trailer and go to Canada. Or down to old Mexico. Find out what is at the end of some old country road. Go see what’s over the next hill, and the one after that, and the one after that.” (Full disclosure: Airstream’s parent company is Thor Industries, Inc., which also owns Roadtrippers.)

Indeed, as Paul and I peruse so many trailers and the cars that pulled them, it’s impossible not to dream about various vehicle combos and dream trips; images of my family spilling out of the door of one of these beauties, in some gorgeous mountain setting, flash through my mind.

We admire a gleaming 1947 Spartan Manor Travel Trailer; a cream-colored, wood-adorned 1959 Ford Country Squire; a clunky red 1965 Great Dale House Car; and a couple of cute, rounded campers like a 1973 Serro Scotty Travel Trailer and a little Shasta trailer.

But for Paul, it’s all about a white and pale blue Travelall. These truck-based crosses between station wagons and early SUVs were built by International Harvester from 1953 to 1975. Paul’s family had one growing up, nearly the same color and year as the one on display, and they went all over the country in it.

“My dad made a car-top carrier out of plywood, where we kept tents and cook gear,” he remembers.

Finally, we wander away, reluctantly, our thoughts in that funny place between warm, wispy nostalgia and the excitement of future adventures. It’s a precarious but fun place to be, and it’s left us rather speechless as we step back outside where our eyes adjust to a crisp, bluebird sky. We get in my car—a well-loved, slush-splattered white 2013 Toyota Sienna minivan—and as we drive away, we imagine pulling a vintage trailer behind it.

If you go:

Forney Museum of Transportation is open Monday-Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Sunday 12 p.m. to 5 p.m. Entrance is $12 adults, $10 seniors (65+), $6 children (ages 3-12). Special Exhibit “Home is wherever you park; Vintage Camping Trailers” runs through March 30, 2019.