In the middle of downtown Hot Springs, Arkansas, a bricked-in pool of water steams in the cool fall afternoon. Nestled against the towering cliffs of Hot Springs Mountain in the Ouachita Mountain range, and across from the historic Arlington Resort Hotel & Spa, the natural pool of water looks soothing and inviting.

But looks can be deceiving. The water temperature averages 143 degrees Fahrenheit in this scalding puddle full of minerals that has seeped through the mountains for thousands of years. Located at Arlington Lawn, this is one of the only visible springs in Hot Springs National Park. Originating on the hill near Grand Promenade and flowing down a steep cliff into two pools, it’s one of the only publicly-accessible hot springs in a town named after hot springs—one of 47 that ooze out of the mountains.

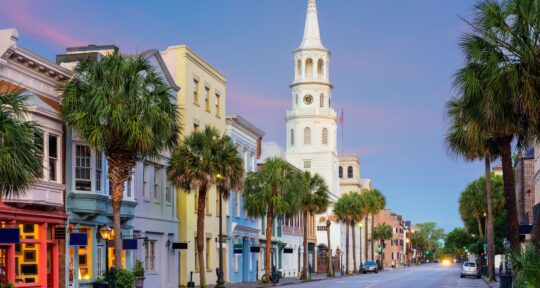

Hot springs created this southwestern Arkansas city, attracting health-seekers for the water’s medicinal properties. Known as “America’s Spa” in the early 1900s, Hot Springs was also the home of Major League Baseball’s spring training and Prohibition-era speakeasies. The town is completely surrounded by the national park, one of the country’s smallest (5,500 acres), second only to Gateway Arch National Park.

Although Hot Springs National Park was officially designated on March 4, 1921, the area received federal protections in 1832, making it one of the oldest of the 63 parks (the newest is West Virginia’s New River Gorge). The park will celebrate its centennial all year long with a campaign that asks for 100 hours of volunteer work; a challenge to walk, bike, or paddle for 100 miles in Arkansas’ wild places; and hundreds of other activities.

Healing waters

The resort town of Hot Springs, located about an hour southwest from Little Rock, is a hybrid of sorts. One side of the main street includes hotels, boutique shops, and restaurants, while the other side belongs to the national park with its medicinal waters, miles of hiking and biking trails, and the historic Bathhouse Row.

Unlike those famously found in Yellowstone National Park—a prime example of how the boiling Earth’s core can create scalding water that rises to the surface—the hot springs in Arkansas are more subtle. No geothermal magic occurs here. Instead, a combination of time and pressure causes cold rainwater from more than 4,000 years ago to swelter into burning temperatures.

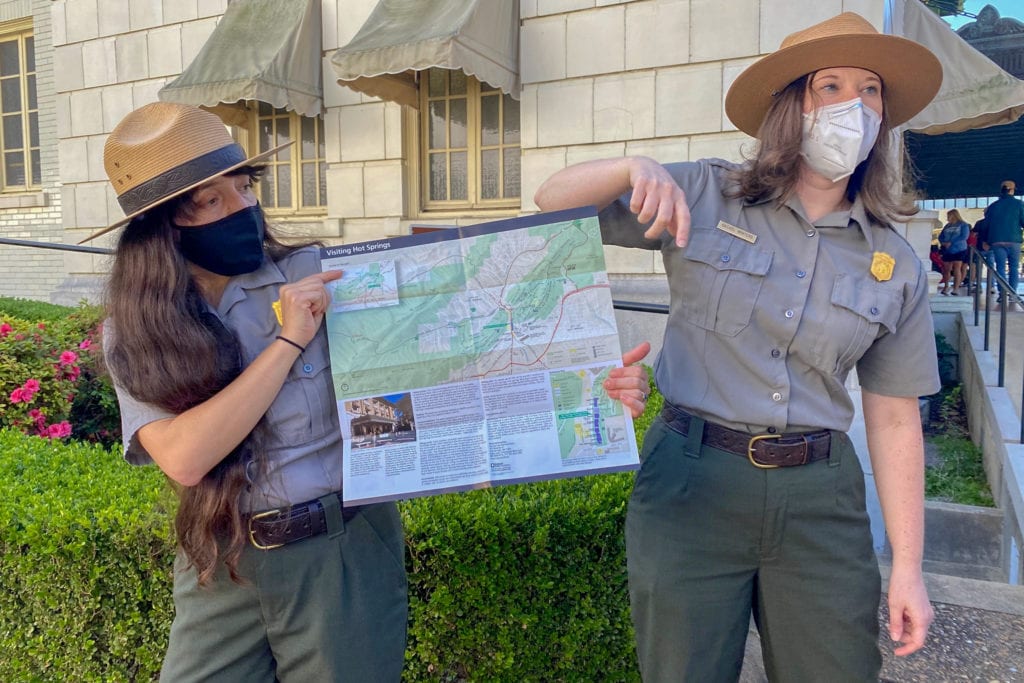

How a quiet Arkansas town is becoming a top-tier street art destination

“Imagine a rainy day,” says park ranger Ashley Waymouth. “Rain is hitting all over these mountains, right where we are. That water is going through the rocks for 6,000 to 8,000 feet beneath the surface. It's taking thousands of years to travel down, and it gets hotter and hotter, dissolving some of the minerals into the water itself. That’s why the water here is so famous for its health benefits. But this is the first time the water has been exposed to the surface in 4,400 years.”

I’m looking at water that might have fallen as rain before the pyramids were built in Egypt. It fell when the Ouachita Mountains were still young, and trickled slowly through the rock for centuries, rising in temperature, before finally seeing sunlight again in a world that is vastly different from what it remembered.

The outdoors has always played a major role in Hot Springs. In addition to soaking in the warm mineral baths at the spas, patients were encouraged to walk the trails around the city as part of their treatments. Outside of Bathhouse Row, visitors can hike more than 30 miles of trails. The rugged and green Ouachitas boast scenic drives, hot water cascades, picnic areas, and campsites at Gulpha Gorge Campground. Accessible from Central Avenue, the West Mountain, Hot Springs, and North Mountain trails are popular; the 10-mile Sunset Trail weaves through some of the more remote areas of the park.

As I wander down Bathhouse Row, I take a short detour of the main path to the Peak Trail, which shoots up Hot Springs Mountain to a famous observation tower, open to the public since 1983. Although the 216-foot-tall tower has an elevator, the more than 300 steps present a fun challenge; I’m rewarded with a 360-degree panoramic view of the entire park from the observation deck.

A rowdy history

Hot Springs’ medicinal waters—and the fact that gambling and horse racing were more or less tolerated in the area—also attracted gangsters. From its inception throughout the mid-1900s, Hot Springs was the favored hangout of such infamous mobsters as Frank Costello, Bugs Moran, Al Capone, and Lucky Luciano. Former President Bill Clinton was born in Hope and put Little Rock on the map, but he lived in Hot Springs between 1954 and 1961.

Welcome to the Wine Capital of Arkansas

Gambling was illegal in Arkansas at the turn of the century, but Hot Springs judges and law enforcement more or less turned a blind eye. When Owney “The Killer” Madden, also referred to as “The English Godfather,” was released from prison in 1935—and told by prosecutors that he was no longer welcome in New York City—he made Hot Springs his home. Madden created a small criminal empire and large illegal gambling operation, which attracted mobster friends and political figures alike to Hot Springs.

Today, visitors can relive the bad old days at The Gangster Museum of America, located along Central Avenue in downtown Hot Springs. Those looking to partake in now-legal gambling activities can do so at The Oaklawn Racing Casino Resort.

Quaff the elixir

When visiting Hot Springs, you won’t need to look any further than Bathhouse Row for lodging. The eight historic bathhouses are getting a new life thanks to a unique public-private partnership. Nationwide, NPS maintains more than 8,000 historic buildings and authorizes their use and maintenance to non-federal parties. But for decades, federal appropriation levels have been insufficient to keep up with the maintenance needs for these historic resources, and Hot Springs National Park now leases these buildings to businesses for maintenance and upkeep.

Two of the renovated historic bathhouses located at the heart of Central Avenue have reopened as The Waters Hot Springs and Hotel Hale. With nine individual suites—each with a large soaking tub that pumps hot spring mineral water directly into the room—Hotel Hale, built in 1892, is the oldest structure on Bathhouse Row.

No visit to Hot Springs would be complete without grabbing breakfast at the famous Pancake Shop open on Central Avenue since 1940. Nearby, McClard's Bar-B-Q opened in 1928 and has remained a family business ever since. Catering to presidents and celebrities, Scott McClard is the fourth-generation owner of the eatery, and McClard’s still serves up local fare.

After a salty dinner at McClard’s, visitors will be grateful that the NPS’s answer to the question, “Is the water from the hot springs good to drink,” is the same today as it was in the 1800s: “Drinking the hot springs water is perfectly normal, even encouraged. Go ahead. ‘Quaff the elixir,’ as they used to say in the heyday of the spa.”

Today, hundreds of thousands of gallons of water still flow out of the mountain springs into a reservoir system; the water is plentiful enough for the commercial baths and for the free “jug fountains” located in town. Every day, locals and visitors alike haul empty gallon jugs and containers to the fountains to fill with the mineral waters—but Waymouth cautions that it’s not exactly an all-you-can-drink buffet.

“We constantly ask ourselves how we can better monitor and protect these springs,” she says. “The springs are so delicate and make anywhere between 600,000 and 800,000 gallons a day. That sounds like a lot, but it's not actually, especially when you think we're giving it away for free. We really have to be conscious of the way that we manage it and the way that we interact with it.”