Le Roy is a small, rural town that sits quietly along Interstate 90 in Upstate New York. About halfway between Buffalo and Rochester, it’s passed daily by local drivers and tourists on their way to Niagara Falls.

At first glance, Le Roy may seem pretty insignificant to most, but a single bright yellow billboard clues outsiders in on the town’s little-known claim to fame: It’s the official birthplace of Jell-O, the world-famous gelatin dessert that has become one of the most well-known brands in American history. Travelers will learn all this and more if they follow the billboard’s directions to the Jell-O Gallery, a museum that celebrates Jell-O’s history, its ties with the town, and all of its jiggly, wiggly, fruit-flavored goodness.

I step off of East Main Street and onto the “Jell-O Brick Road” that leads up to the museum’s entrance. It’s covered in white, fluffy snow, but I later learn that each brick along the path is inscribed with the names of former employees at the original Jell-O factory here in Le Roy.

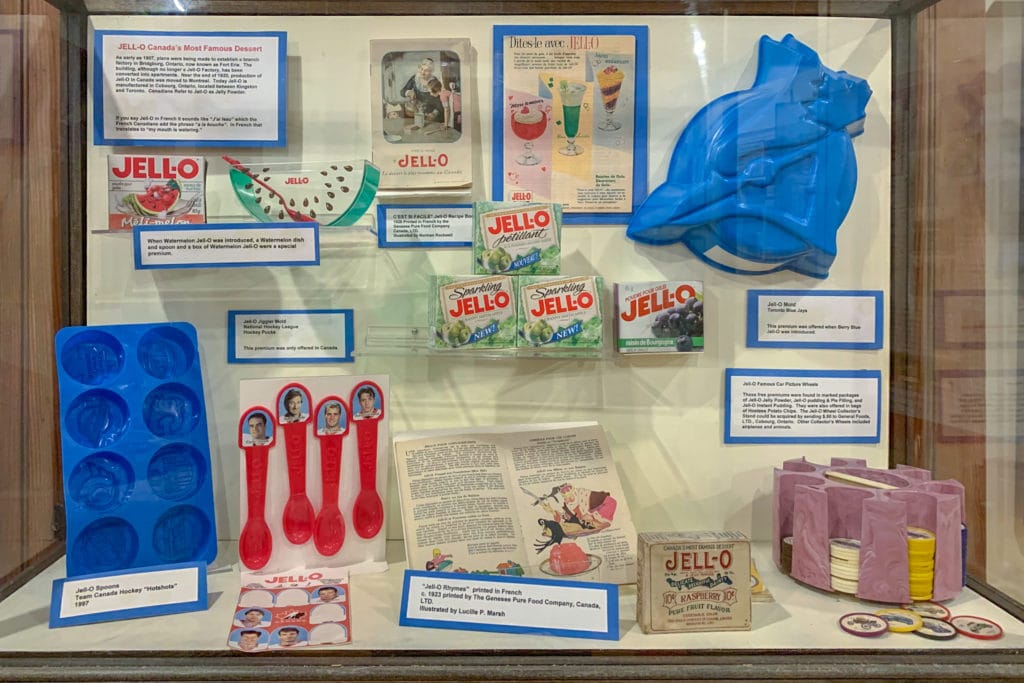

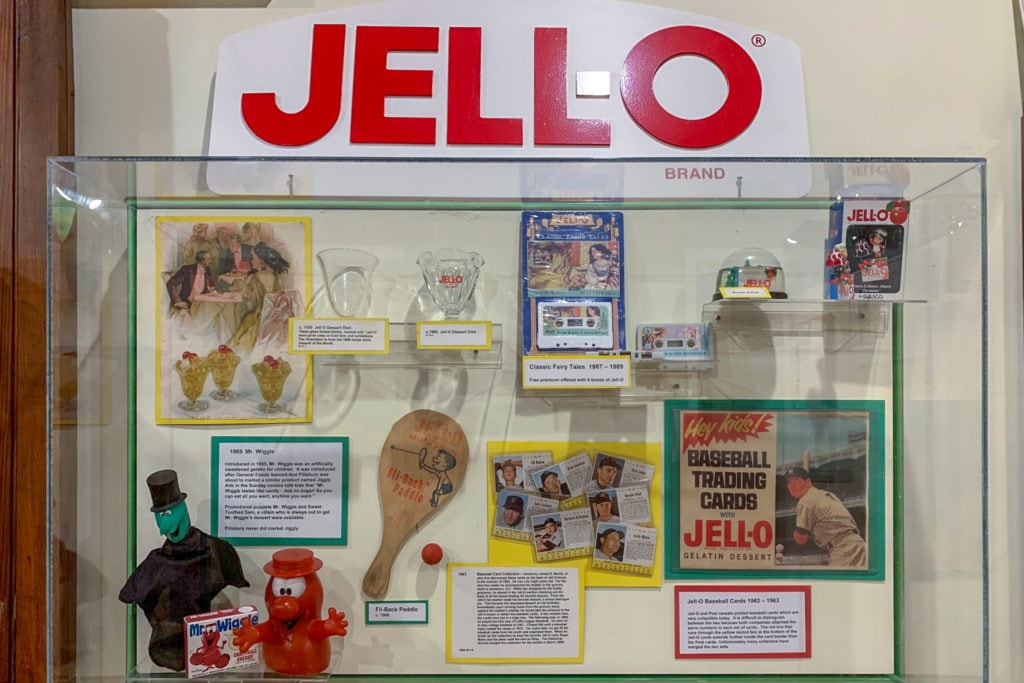

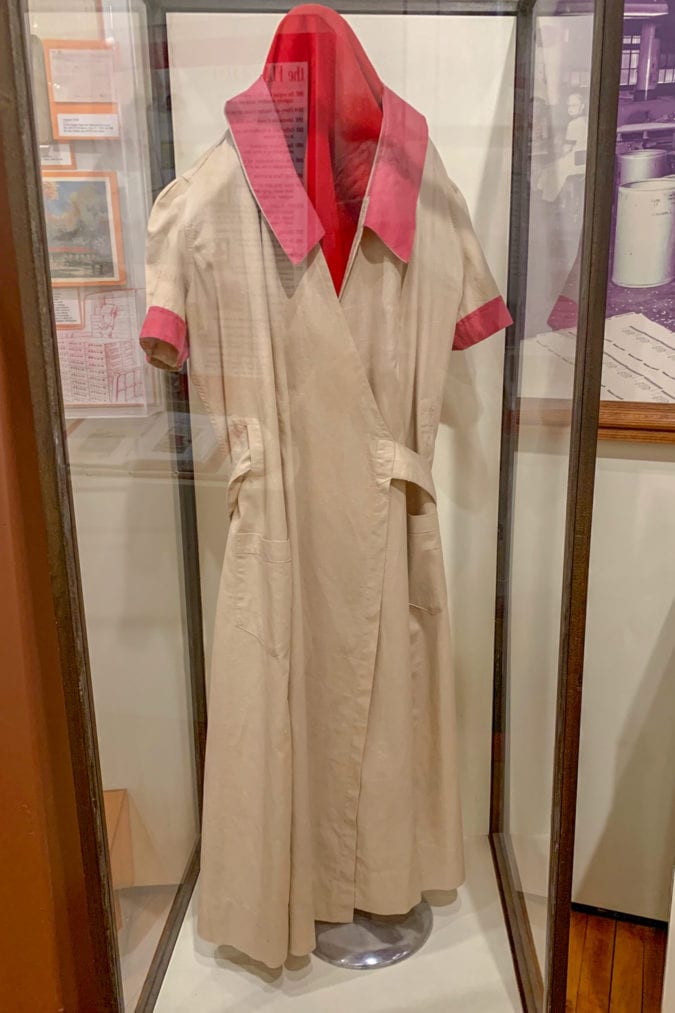

The museum is located inside of a historic building that was once the town’s schoolhouse, and Jell-O fills every possible square inch. Vintage memorabilia, original advertisements, and tchotchkes galore line the walls and hang from the ceiling, and as I move throughout the gallery, each exhibit invites me to further immerse myself in the story of this quintessential American dessert—one bite-sized piece at a time.

The birthplace of Jell-O

Long before Jell-O made its way to Le Roy, it was simply known as gelatin. In its earliest days, gelatin was a symbol of wealth and social status in Europe, mostly because it took hours to prepare and was expensive to store before advanced refrigeration technologies became available to the general public. Serving a gelatin dish at a dinner party—especially in a fancy brass mold—would have been a flashy indicator that you had the means to support a kitchen staff with the skill to create such a complicated dish.

It wasn’t until the year 1897, when a Le Roy businessman named Pearle Wait began experimenting with flavored gelatin recipes in his kitchen, that the official Jell-O brand gelatin recipe was born. Wait made a living manufacturing cough syrup and laxatives, but when business suddenly slowed to a halt, he decided to try his hand in the food industry.

Wait was in charge of the recipe, which democratized the dessert for the first time by turning it into a flavored powder that could be reconstituted quickly—and for just a few cents per serving. His wife, May, created its signature look, molding it into as many different shapes as she could come up with. She is also said to have coined the name “Jell-O,” in hopes that it would help differentiate it from other gelatin products on the market.

For a few years, the Waits tried to market the product to the public, but without any skills or expertise in sales or advertising, they weren’t able to get any traction. The couple sold the Jell-O trademark and business to a fellow Le Roy townsman, Orator Frank Woodward, in 1899 for just $450—the modern-day equivalent of $4,000.

“It doesn’t seem like much by our standards now, but that was actually a lot of money back in those days,” says Lynne Belluscio, director of the Jell-O Gallery. “Especially for something that wasn’t really selling.”

By the time Woodward purchased the Jell-O business from the Waits, he was already an experienced packaged foods salesman, well-versed in the world of marketing. But he, too, struggled with selling the product at first. Le Roy myth even claims that Woodward, exasperated by poor sales numbers during Jell-O’s first few years, tried to sell off his entire Jell-O inventory to a friend for $32. Luckily for him, the friend declined the offer.

Once Jell-O finally took off, combining such a unique product with Woodward’s expertise in sales turned out to be a match made in dessert heaven.

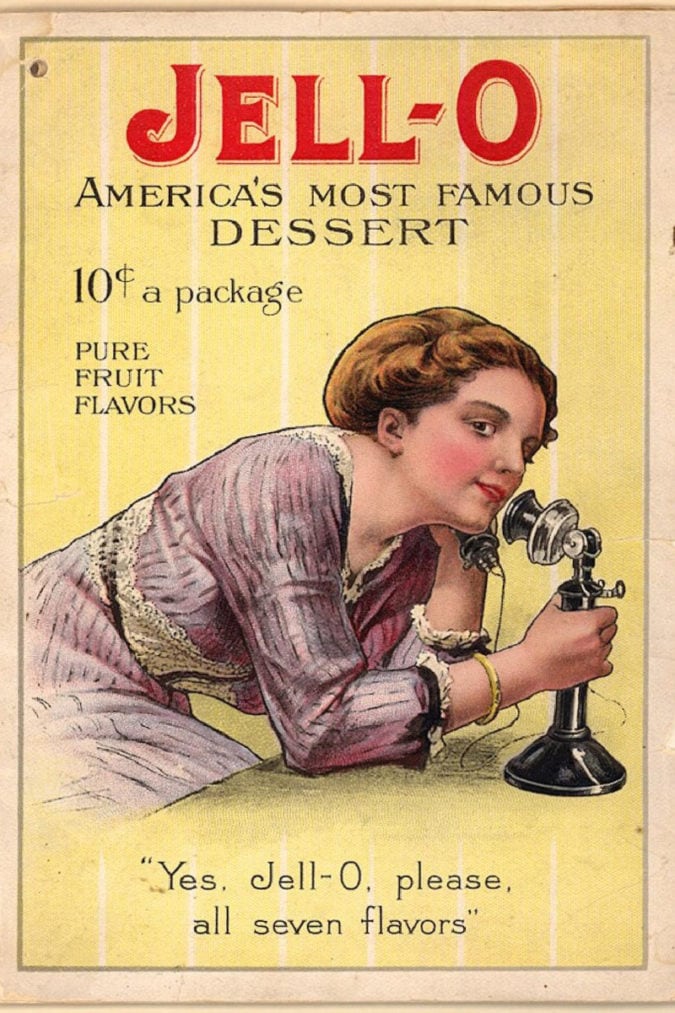

Determined to sell Jell-O by any means necessary, Woodward sent his handsomest salesmen out in horse-drawn carriages to go door-to-door in suburban communities. They provided housewives with free samples, taught them how to prepare it, and left them with complimentary recipe booklets for further inspiration. Just before leaving town, the salesmen would visit the local grocery store, attempting to persuade the owners to stock Jell-O. Once they achieved their desired results, they moved to the next town, and the cycle continued in cities and small towns across the country. Jell-O sales soared.

“How Jell-O got its start is really an interesting case study in marketing and advertising,” says Belluscio. “And once they got the ability to print their ads and store displays in color, things took off even more. People were suddenly attracted to this colorful new product.”

Preserving Jell-O’s history in Le Roy

Today, Jell-O is manufactured by the Kraft Heinz Company and General Foods Corporation in Dover, Delaware. The original Jell-O factory in Le Roy closed in 1964, but the Le Roy Historical Society (led by Belluscio) continues to ensure that Jell-O’s history is well preserved here in Upstate New York.

The Jell-O Gallery first opened to the public during the summer of 1997, in celebration of the dessert’s 100th anniversary. But back then, the Historical Society didn’t have nearly the extensive collection that it has today.

“When I started working here, we had very little Jell-O stuff available to us, I think because people were still bitter that they moved everything to Dover,” Belluscio explains. “All we had were a few oil paintings that were hung in the original factory, and that’s why we still call it a gallery today.”

Since then, Belluscio and her team have collected myriad historical Jell-O treasures wherever they can find them, from the tables of flea markets to the shelves of local thrift stores, and sometimes even through generous donations from the public.

I find one of the museum’s latest additions at the back of the gallery—an exhibit dedicated entirely to a collection of Jell-O molds, in what feels like just about every material, size, and shape combination imaginable. Some are neatly hung on the walls, others are showcased in plastic shadow boxes, and some even spill out onto the floor; there simply isn’t enough room to fit them all in one space.

“Oh, hundreds,” Belluscio says when I ask how many Jell-O molds the museum has collected in total over the years. “Honestly, we still need to figure out what to do with them all.”

More than a century after its creation, it’s clear that Jell-O still plays a huge role in the identity of Le Roy. I leave the Jell-O Gallery not only with a sudden hankering for some Jell-O (orange is my favorite), but with a newfound appreciation for small towns everywhere.

“All culture is local culture, and all small towns have a story to tell,” Belluscio says. “That’s one of the best parts of my job—I get to share Le Roy’s story with people who didn’t even know it existed.”

If you go

The Jell-O Gallery is temporarily closed due to COVID-19 restrictions but hopes to open in the spring. Please contact the Jell-O Gallery or check Facebook for the latest information.