It’s an unusual success story: Madam C.J. Walker, a child of freed Louisiana slaves born soon after the Civil War, launched a hair care empire that turned her into the first Black female self-made millionaire in the U.S. (or first woman of any race, according to some accounts). A hundred years after her death in 1919, Walker was the subject of the 2020 Netflix series Self Made, starring Oscar winner Octavia Spencer.

In Indianapolis, home of the headquarters of the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, visitors can follow a self-guided walking trail to discover how Sarah Breedlove (Walker’s given name) became Madam C.J. Walker, an entrepreneur, philanthropist, and celebrity. Stops include an absorbing, interactive exhibit where costumed actors portray key characters in Walker’s life, a legacy center housed in her former factory and headquarters, a massive mural, the church where she worshipped, and a portrait of her made—very fittingly—from almost 4,000 hair combs.

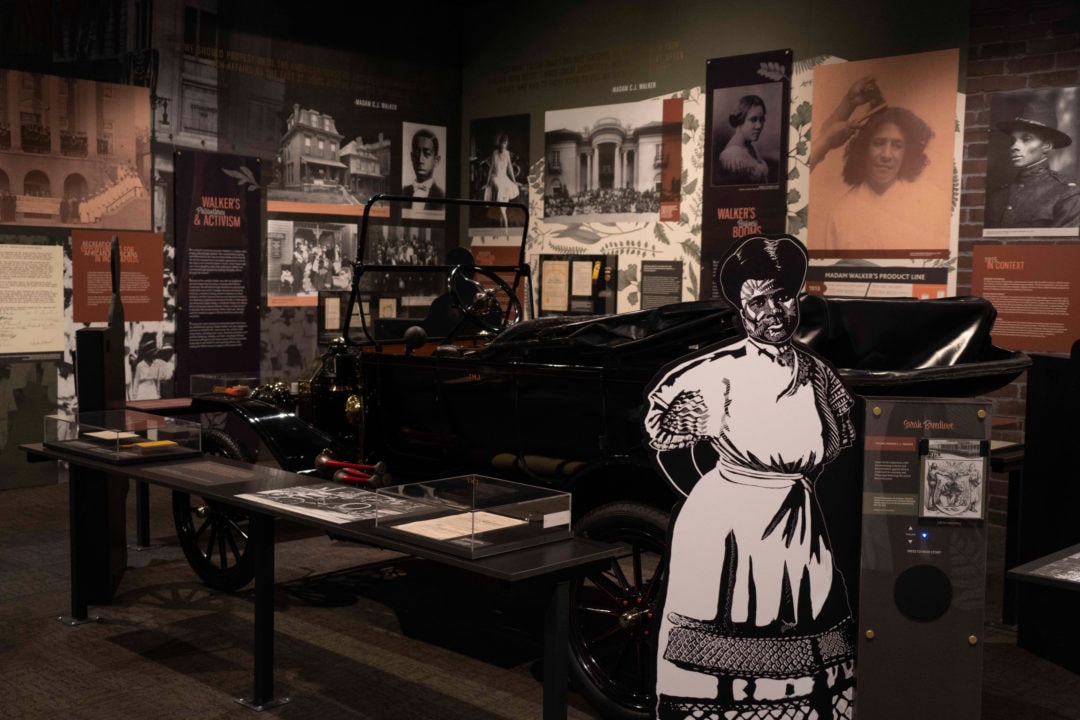

At the Indiana Historical Society, an exhibit recreates Walker’s office on a day in 1915, based on a photograph in the society’s collection. Visitors are encouraged to ask questions of the actors in period dress, who portray Walker and major figures in her life, most of whom were also Black. Her lawyer, Freeman B. Ransom, led day-to-day company operations for decades; Alice Kelly was her factory forewoman; and George Knox was editor of The Indianapolis Freeman, the first illustrated Black newspaper in the U.S.

The society’s collection of about 11,000 Walker-related materials ranges from original hair product tins, brochures (“Open your own shop; secure prosperity and freedom,” one urges), newspaper ads, fliers for national beautician conventions, and elegant portraits. A press release from 1960 announces that the U.S. Ambassador to Ghana visited for the company’s 60th anniversary. Walker’s personal correspondence includes her will and a passport application to Paris.

“That’s one of my favorites,” says Susan Hall Dotson, coordinator of African American history at the Indiana Historical Society. “It shows the places she traveled, from Costa Rica and Haiti to Jamaica, where she sold her products by shipping to local customs agents.” The society’s current exhibit, You Are There 1915: Madam C.J. Walker, Empowering Women, runs until April 2022.

A widow and mother

The deck seemed stacked against Walker from the beginning. Born in 1867 to sharecroppers who died young, she picked cotton, became a laundress, married at 14, and had a child at 17. “At age 7 she was an orphan. At 20, she was a widow and a mother,” says Dotson.

Making matters worse, she was also losing her hair. Her great-granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, wrote in an essay: “During the early 1900s when most Americans lacked electricity and indoor plumbing, bathing was a luxury. As a result, Sarah and many other women were going bald since they washed their hair so infrequently.” Being overworked, often undernourished, and under constant stress didn’t help. (Bundles also authored Walker’s biography, On Her Own Ground.)

When Walker moved to St. Louis, she met Annie Turnbo Malone, who had invented a product to promote hair growth in Black women. Walker became Malone’s sales agent, selling the product door-to-door. Later, Walker moved to Denver and created her own recipe. She was nearly 40 years old when she married Charles J. Walker, a newspaper salesperson, and took his name.

Marketing genius

After moving to Pittsburgh, Walker opened a small factory and her first beauty school to train women in hair care and styling. But she decided to make Indianapolis her national headquarters, and opened a big manufacturing plant on Indiana Avenue in 1910.

“Indianapolis was called the ‘crossroads of America’ at the time, with a central location and ease of shipping nationally to eastern and western states,” says Dotson. “She got a warm reception here, and Indiana Avenue had many African American-owned businesses.”

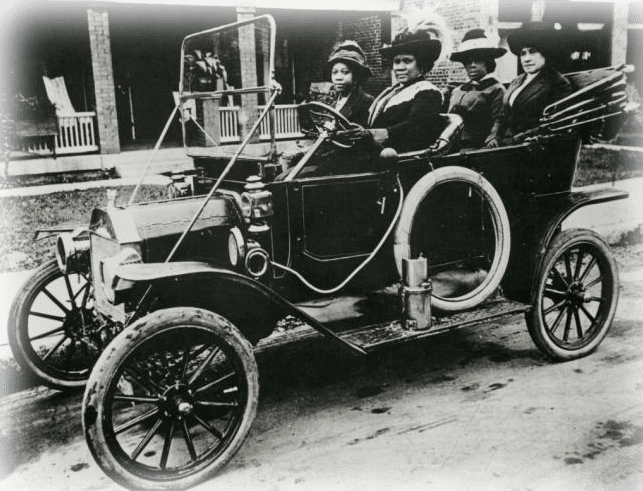

A marketing genius—whose name and face adorned the packaging for her many hair products, sometimes in before-and-after transformation photographs—Walker pioneered the concept of personal branding, inspiring customer loyalty decades before Martha Stewart and other lifestyle gurus did the same.

“Sarah was ahead of her time in branding her business. Her name and image appeared on all her products,” says Dotson. “She had only a third-grade education, but was always learning.”

Another brilliant move was naming her firm “The Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company,” a majestic moniker at a time when Black women were routinely called by their first names or the condescending “Auntie.” The name change to “something both catchier and more dignified was a smart career move that reflects her style and marketing flair,” wrote Nancy Koehn, a professor who teaches Walker’s story in her class on entrepreneurial leadership, in a Harvard Business School case study. Even after divorcing her husband in 1912, Walker kept the name, knowing her brand identity was inextricably tied to it.

In 1916, Walker moved to Harlem to be near her daughter. She later built Villa Lewaro, a columned mansion in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, but she kept her headquarters in Indianapolis. She employed thousands of women as sales agents, and owned several beauty colleges to train Black women in hair care and styling. “I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself,” Walker said in 1914. “I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of women of my race.”

Black tax

The Madam Walker Legacy Center, located in her former factory on Indiana Avenue, is a 10-minute walk from the historical society. The 1928 building, a National Historic Landmark completed after Walker’s death, is also home to The Walker Theatre. Nat King Cole, Lena Horne, and Ella Fitzgerald sang beneath the building’s ornate light fixtures featuring African motifs.

“Walker once had to pay a ‘Black tax’ at a theater in Indianapolis, so she wanted a theater,” says Kristian Stricklen, the center’s president. The center plans to offer cultural and entrepreneurial programs when it reopens in the fall, after a major renovation was delayed by COVID-19. Walker had a home located behind the factory, but like her grand Harlem residence, it has since been demolished. (Villa Lewaro still stands, but is not yet open to the public.)

A large mural depicting Walker, her humble beginnings, products, and women employees was unveiled at the Indianapolis International Airport in February. Featuring quotes from Walker herself, local artist Tasha Beckwith was chosen for the project by the Legacy Center, airport authority, and Indiana Arts Council.

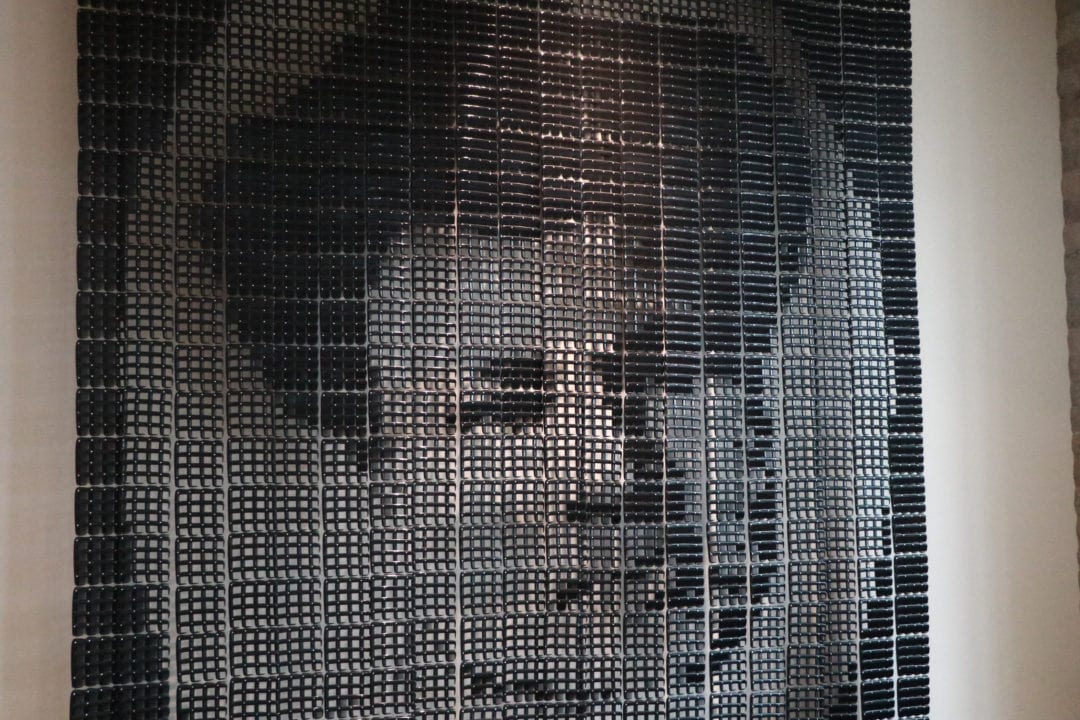

On display at the The Alexander Hotel is Walker’s hair-comb portrait by artist Sonya Clark. Located just past the bar, visitors can order a “Self Made” cocktail (grapefruit and rose vodkas, raspberry simple syrup, and cranberry juice) and raise a toast to the indomitable woman who overcame poverty, hardship, and discrimination to become a millionaire—with really good hair.

If you go

Admission to the Indiana Historical Society is free to teachers, healthcare workers, first responders, and military with ID.