It’s a gross understatement to say that a lot of Black history has been swept under the rug over the centuries, but according to Alan Spears, senior director of cultural resources for the National Parks Conservation Association, the National Park Service (NPS) is working hard to correct some of that. “The parks and their history belong to all of us,” says Spears.

Inspiring stories are being highlighted at NPS sites from coast to coast: The first park rangers at Yosemite were African American, and Black soldiers were charged with protecting Ute lands in Colorado’s Great Sand Dunes region. But even today, just the act of roadtripping to national parks is significant in itself, says Spears.

“Sometimes people still have a fear about getting into a car and going to a remote place like Yellowstone, because they’ve never been and they don’t know if they’re going to be welcome,” he says. “We’re trying to overcome those fears, and that’s a good thing because it leads to a broader coalition of people who love parks, and maybe even a broader coalition of people who will advocate for parks.”

If you’re hitting the road in search of Black history, here are some of Spears’ top recommendations.

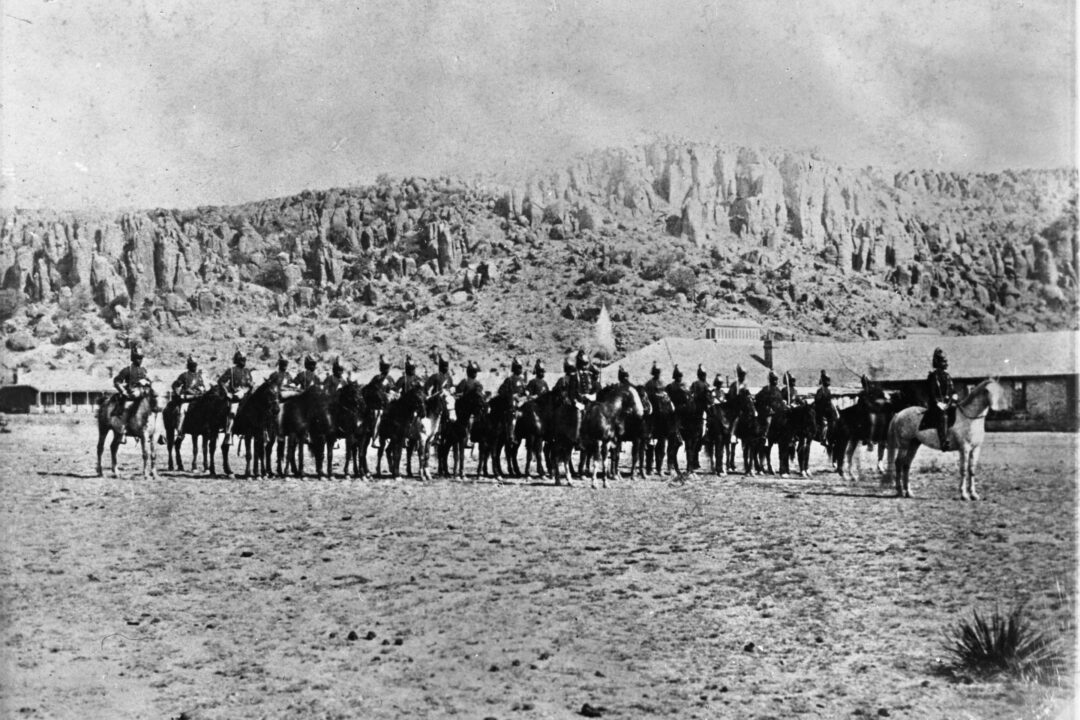

1. Fort Davis National Historic Site, Fort Davis, Texas

Out in the remote Chihuahuan Desert of West Texas, the old barracks of Fort Davis National Historic Site were home to the post-Civil War regiments known as the Buffalo Soldiers. “I don’t think it’s common knowledge that you can get African American history that far west of the Mississippi, but it’s an interesting place,” says Spears. “It tells a story of what those African American troops were doing on the Western frontier, which included helping with westward expansion, building roads, and protecting settlements, but then also the challenging legacy of what those Black guys in blue uniforms were doing to the Indigenous populations.”

2. Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Anacostia, Washington, D.C.

Many people have heard of abolitionist and author Frederick Douglass, who escaped enslavement and went on to serve as a statesman under five presidents, all while advocating fiercely for racial equity and women’s rights. “He was one of the most well-known people in the country, kind of like the Oprah Winfrey of his day,” says Spears.

In 1877, Douglass bought a home on Cedar Hill in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, D.C., which would become his namesake historic site. Since the house was in a part of the District with covenants against African Americans and other groups owning property, it was particularly significant that he made it both his family home and command post. Today, the house and its contents are mostly original.

3. Black Heritage Trail, Boston, Massachusetts

Along the 1.6-mile Black Heritage Trail, a walk through Boston’s traditionally African American neighborhood, Beacon Hill, stops range from the Granary Burying Ground gravesite of Crispus Attucks—a Black sailor killed by British troops during the Boston Massacre, who is now considered the first casualty of the American Revolutionary War—to the Underground Railroad safe house of Lewis and Harriet Hayden.

“When the Fugitive Slave Act was passed [in 1850], you were told if you were harboring any fugitives, the marshals were going to come kick in your front door, arrest the fugitives, and take you to jail,” says Spears. “Hayden allegedly told authorities that he had a couple of kegs of dynamite near the front door and if anybody tried to raid his home and arrest the fugitives, he would rather blow up his house than surrender to the authorities.”

Most sites on the trail must be viewed from the sidewalk, as they are private residences, except for the Abiel Smith School and African Meeting House, which are part of the Museum of African American History. The trail also connects with the Freedom Trail, which showcases important sites from the American Revolution and beyond.

4. Freedom Riders and Birmingham Civil Rights National Monuments, Alabama

A Greyhound bus lit on fire by the Ku Klux Klan is one of the more infamous and haunting images from the civil rights movement. Today, the Freedom Riders National Monument and Anniston Civil Rights and Heritage Trail commemorate the protestors aboard that bus, some of whom were beaten and burned for drawing attention against segregation on public and interstate transportation.

“The Freedom Riders continued on to Birmingham, where they had an even hotter reception,” says Spears. “At that point in time, Birmingham was regarded as the most heavily-segregated city in the U.S.”

By the early ‘60s, other Southern cities, including Memphis, had desegregated lunch counters, but public officials in Birmingham were still launching water cannons at nonviolent protestors and sending in police dogs. “The idea was, if you can successfully fight segregation in Birmingham, maybe you can fight it anywhere,” says Spears.

7 Black history museums in the U.S. to visit year-round

Today, many of these stories are told at the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, the nearby 16th Street Baptist Church (site of the 1963 bombing that killed four young girls), Kelly Ingram Park, and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

In Alabama, the NPS also maintains the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, which lends itself well to a driving tour. Retrace the route of the 1965 marches from the Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in Selma to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and end at the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery.

5. Biscayne National Park, Homestead, Florida

The lucid waters, coral reefs, and mangrove shorelines of Florida’s Biscayne National Park are preserved as public lands thanks to a family of Black farmers. At the turn of the 20th century, philosopher and preacher Israel Jones and his wife Mozelle built their homestead on an island in south Florida, then became some of the most successful lime producers in the state. In 1929, they handed the farm over to their sons, King Arthur and Lancelot, who started a bonefishing guide service, entertaining the likes of Herbert Hoover and Richard Nixon.

“They eventually ceded their property over to the NPS, even though they were receiving offers from people who wanted to develop it,” says Spears. Today, the Jones Porgy Key homesite is accessible via shallow-draft vessel.

6. Rosie the Riveter National Historic Park, Richmond, California

The woman wearing a red bandanna and flexing her bicep became an icon of WWII—but the white lady featured on the famous “We Can Do It” posters is only part of the Rosie the Riveter story. “There were Black Rosies and Brown Rosies as well,” says Spears. “Like Fort Davis, the name of the park doesn’t really give you any sense that there would be African American history involved there, but there were a lot of women of color involved in wartime production.”

Until 2022, one of the original Black Rosies, Betty Reid Soskin, worked as a ranger at the park, helping create programming that accurately portrayed the lives of African and Japanese Americans during WWII.