Nestled among concrete skyscrapers and bustling city life lies an unassuming collection of misleading exteriors hiding unsightly infrastructure. Among those in the know, they’re called fake facades.

In a city as big and as old as New York, there are bound to be a few secrets—and these buildings are some of the best or worst kept ones, depending on who you ask. “Infrastructure gets hidden for a number of reasons—aesthetics is a big one—but sometimes it’s just the nature of where the infrastructure needs to be built,” says Jodi Shapiro, curator of the New York Transit Museum.

See inside of NYC’s dazzling, abandoned City Hall station

Every day, these buildings dupe locals and tourists alike. Whether you’re a resident or just visiting for a few days, make sure to check out these four New York City buildings that are hiding in plain sight.

1. 58 Joralemon Street, Brooklyn

If you ask Nick Carr, a Los Angeles-based movie location scout who previously ran the blog Scouting NY, 58 Joralemon Street is one of the city’s worst-kept secrets. “If you take four seconds to stop and look at the building, you realize it doesn’t look right,” he says.

The building resembles any other townhouse on the picturesque tree-lined street in the neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights, but it’s actually a subway vent and emergency exit. Now dubbed as New York’s only “Greek Revival vent,” it was once an actual residential home. “It certainly had several owners, but it was bought by Patrick Brennan in 1883,” says Alice Griffin, an archivist at the Center for Brooklyn History at Brooklyn Public Library. Newspaper clippings show the Brennans soliciting a housekeeper and babysitter, and even an obituary for their youngest son’s death in 1893.

In 1907, the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) Company, the original private operator of New York’s subway system, acquired the property, gutted the inside, and turned it into the ventilation shaft it is today. “It was most likely vacant and they seized the opportunity,” Shapiro says.

The vent was necessary to finish construction on the 6,000-foot tunnel the company built to run subway lines beneath the East River and connect Brooklyn to Manhattan. An article from 1907 in the New York Tribune describes ventilating the subway line as an “intricate and almost unprecedented problem.” The IRT needed land as close to the river as possible and almost bought a house on Hicks Street (also in the neighborhood), before ultimately closing on 58 Joralemon.

“The first thing you see is that the windows are all blacked out and the door is pretty industrial looking,” Carr says. Though you may be fooled after a quick glance, look a little closer and the illusion will start dissolving.

2. 415 Bruckner Boulevard, Bronx

You won’t see anyone grabbing their mail or watering their flowers in these Bronx “townhouses.” Like 58 Joralemon Street, no one lives in them. However, unlike their Brooklyn counterpart, no one ever has. Instead, these movie-set-esque facades were designed by the Switzer Group, an interior architecture company, to hide an electric substation owned by ConEd, New York’s utility company.

“I actually did a double-take and had to go back because at first, it looked like a gated housing community,” Carr says of his first time seeing the massive plant. “It’s insane how much it looks like every [studio] backlot in Los Angeles.”

Substations like these are necessary to reduce high-voltage electricity to a lower voltage so it can be distributed locally; however, they’re not always the most attractive piece of infrastructure in cities. “I appreciate that they went out of their way to put a little bit of charm to what could have just been a very boring and bland industrial installation,” Carr says.

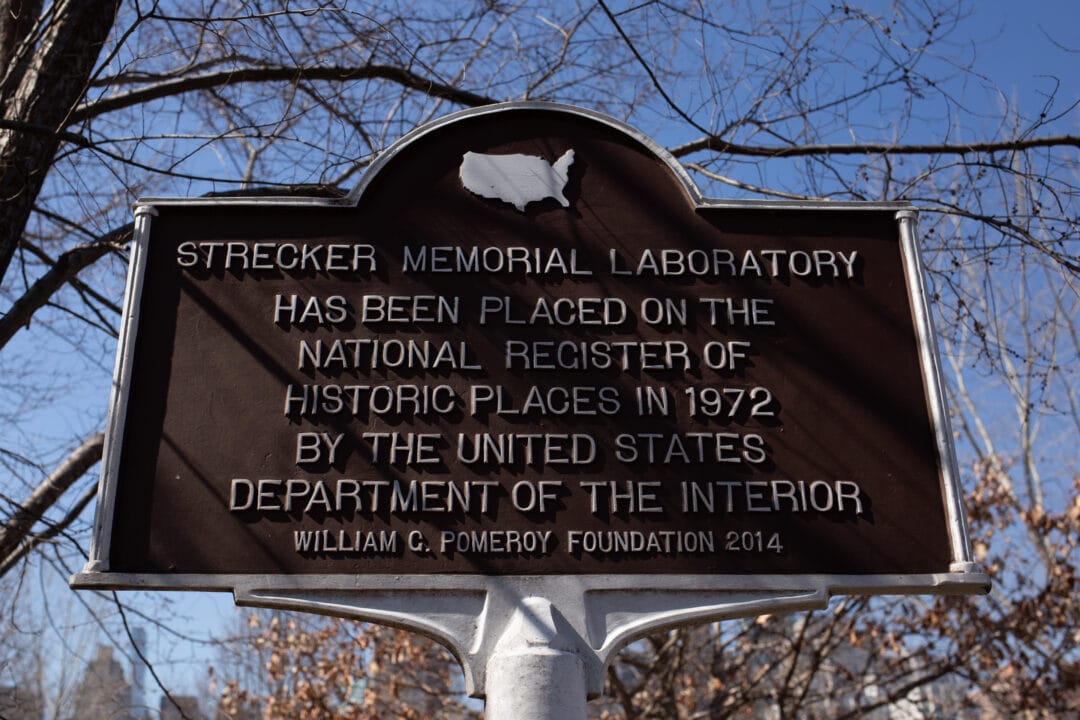

3. Strecker Memorial Laboratory, Roosevelt Island

On the southern end of Roosevelt Island, located in the East River between Manhattan and Long Island, sits a small neo-Romanesque-style structure with arched windows and stone walls. Situated between medical facilities, this building used to be a laboratory for pathological research and medicine—the first in the country dedicated solely to this.

For much of the early 1900s, Roosevelt Island, at the time called Blackwell’s Island, physically isolated various populations from the rest of New York City. Prisons, asylums, almshouses, hospitals for “incurables,” and, briefly, a smallpox hospital were built and in use here until about the 1950s, when most of the structures, including the laboratory, were abandoned as patients, residents, and inmates were moved to different facilities.

In 1972, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP); later, in 1976, the laboratory was designated a New York City landmark by the Landmark Preservation Commission. When this decision was made, the committee described the building as “an outstanding architectural composition with its fine massing of elements organized into a coherent whole.”

Though most of the historic buildings on the island have been repurposed or preserved in ruin, the laboratory’s story mimics that of 58 Joralemon. The New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) decided to convert the structure into a power conversion station for the E and V subway lines. “The Strecker laboratory probably became a substation because the structure is on the NRHP but was too far gone to be made safe,” Shapiro says.

In 1999, the NYCTA hired Page Ayres Cowley Architecture, a firm that specializes in historic structure preservation, adaptive reuse, and restoration, to update the building. The firm restored the exterior, revamped the interior and won a Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award for its efforts. The substation has been running since 2000.

4. Mulry Square, Manhattan

Potentially the worst disguise on this list, the fake facade in Manhattan’s Mulry Square likely wouldn’t fool anyone. When the MTA first revealed plans to build another subway ventilation plant in Greenwich Village, residents weren’t pleased with the original proposed designs to create a faux exterior. “Word has it that, even without the facade, the structure is a complete clunker,” Curbed reported at the time. The MTA went back and forth with the local community board before the transit organization moved forward with a design that’s less than deceptive. “I don’t know if you want to call it unfinished or badly hidden,” Carr says.

The final result looks more like a brutalist concrete box with Velcroed bricks on its exterior. The inclusion of windows without glass makes the disguise that much less effective, as the opening shows the frigid gray just behind the bricks. Still, as Carr says, “It’s not great, but it could be way worse.”