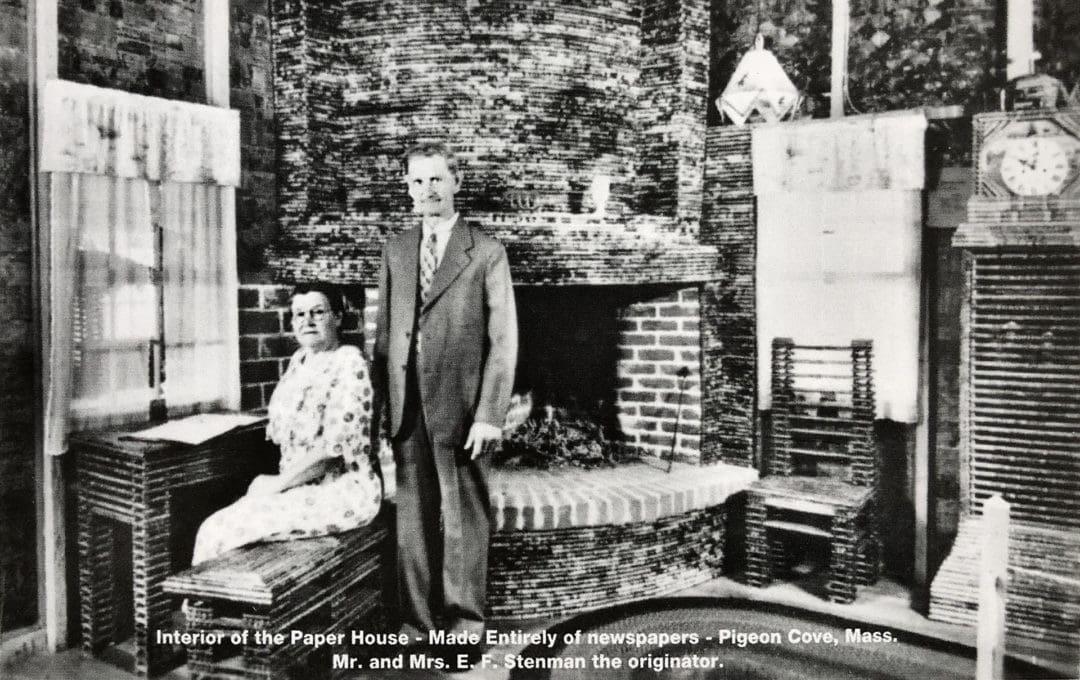

The question that arises most frequently with visitors to the Paper House is the one that no one can really answer: Why would anyone build a house—and most of its furniture—using more than 100,000 newspapers? That someone was Swedish immigrant Elis Stenman, a mechanical engineer who lived with his wife, Esther, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In 1922, the Stenmans began constructing a summer home in nearby Rockport, a seaside town located on the eastern tip of the Cape Ann Peninsula. The home is built with a traditional wood frame and roof, but the walls and insulation are made entirely of varnished newspapers. The home is furnished with a table, chairs, lamps, a settee, a desk, a cot, a radio cabinet, curtains, a bookshelf, a fireplace, and a grandfather clock—all of which are made from rolled newspapers.

The house, which is now sandwiched in between two other private homes, is open daily for self-guided tours from April until October. Visitors are trusted to drop the suggested $2 admission into a box nearby and while photos are allowed, touching and smoking—for obvious reasons—are not.

All the news that’s fit to sit on

The Stenmans used the Paper House as a summer retreat from 1924 to 1929. The house had running water, electricity, and a stove. Although I wouldn’t want to be the one to test this theory, a leaflet provided at the house also insists that the—mostly brick—fireplace is useable. Like most other houses at the time, the Paper House did not have an indoor bathroom. The Stenmans used an outhouse that was not made—but hopefully contained at least one roll—of paper.

The Paper House is sandwiched between two private houses. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The outside is freshly varnished each year. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Paper curtains. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Information about the current ownership of the Paper House is limited, but at some point Stenman’s grandniece, Edna Beaudoin, inherited the house from her mother. In a 1996 interview with the Cape Ann Sun, Beaudoin described her grand uncle as curious. “He wanted to see what would happen to the paper, and, well, here it is, some 70 years later,” she said.

Stenman’s engineering mind wanted to test not only the sturdiness of paper as a building material, but its ability to retain its print. A visit to the house nearly 100 years later proves that his experiment was successful. Headlines, advertisements, and even fine body copy is still very much readable.

The grandfather clock is constructed of newspapers from the capital cities of every state—there were only 48 at the time—and the mastheads are still as fresh as the day they first rolled off their respective presses. A writing desk comprises newspapers announcing the aerial feats of Charles Lindbergh, the cot contains newspapers from the first World War, and the bookshelf is made entirely from foreign newspapers. Even the curtains—made by Esther—are made of paper. The piano is the only piece of furniture in the house that is not constructed of, but merely covered in, rolls of paper.

By the 1930s, the house had become such a popular attraction that the couple moved into a different house down the street. “This is a small town,” Beaudoin said. “Word got around that there was this man making a house of paper.” A decade later, the Paper House opened to the public as a museum. Admission was ten cents.

The persistence of paper

It’s not surprising that Stenman was an avid reader, and he received three different newspapers every morning. The walls of the house are half an inch thick—which amounts to approximately 215 newspapers stacked on top of one another. In a twist on the traditional hoarder narrative, Stenman’s friends and neighbors pitched in by donating their own newspapers to help him keep up with the increasing demand for raw material.

The piano is not made of, but covered in, paper. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan A desk made with Lindbergh headlines. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

Stenman’s true motivations remain a mystery, but Beaudoin suspects they may have been financial. In the years preceding—and following—the Great Depression, money was tight. “I don’t really know why [he built the house out of newspaper] unless he was just really thrifty or something,” she said. “Newspapers were pretty inexpensive; everybody gave him their papers.”

The small logs were made by rolling the newspaper tightly and securing the end with a little bit of glue. Stenman—who designed machines to make wire paper clips and hooks—used a special wire loop tool and tied the rolls with string only long enough for the glue to set.

“He was just that sort of a guy, he was always doing little experimental things,” said Beaudoin. “When he was making the house here, he just mixed up his own glue to put the paper together. It was basically flour and water, you know, but he would add little sticky substances like apple peels. But it really has lasted.”

While the interior has remained virtually untouched since 1942, the exterior is treated yearly with fresh varnish. The porch, built sometime in the 1930s, and traditional shingled roof also help shield the delicate walls from the elements. Nevertheless, the Paper House has persisted in the face of harsh New England winters and several hurricanes.

The papers were tightly rolled and sealed with a bit of glue. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The fireplace actually works and features a paper mantle. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan The dining table and chairs. | Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan Photo: Alexandra Charitan

“Rain blows in, sometimes snow, but it’s held up pretty well considering how old it is,” said Beaudoin. “We really don’t varnish the inside of the house because the more you put on, the darker it gets and we really just like to leave it so you can still read the papers.”

In 1942, Stenman died at the age of 68. We may never know exactly why he decided to spend a third of his life rolling, cutting, and glueing newspapers—but if the last century has proven anything, the Paper House just might have a longer lifespan than print journalism itself.

If you go

The Paper House is located in the Pigeon Cove neighborhood of Rockport, Massachusetts—there are signs directing visitors to the house from the main road but they are small. The house is open daily for self-guided tours, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., April through October.