The San Francisco earthquake of 1906 gets all the attention when it comes to California catastrophes. The massive earthquake, which killed more than 3,000 people, often overshadows the state’s second-greatest loss of life, which came as a result of one of the worst civil-engineering failures of the 20th century.

In 1928, the collapse of the St. Francis Dam and subsequent flood killed more than 400 people. On March 12, 2019—the disaster’s 91st anniversary—the St. Francis Dam site became one of four new U.S. national monuments.

In early 2019, the first piece of legislation introduced to the 116th Congress by newly-elected Representative Katie Hill—from California’s 25th Congressional District—was a bill to establish a memorial at the site of the St. Francis Dam disaster. A companion bill was introduced in the Senate by California Senators Kamala Harris and Dianne Feinstein.

“The St. Francis Dam disaster took place 10 miles north of what is now my hometown of Santa Clarita,” Hill said in a statement. “In honor of the hundreds of lives lost, this memorial will uplift the stories of the tragedy and serve as a constant reminder that our infrastructure is deeply important to our community safety and security.”

Dam shame

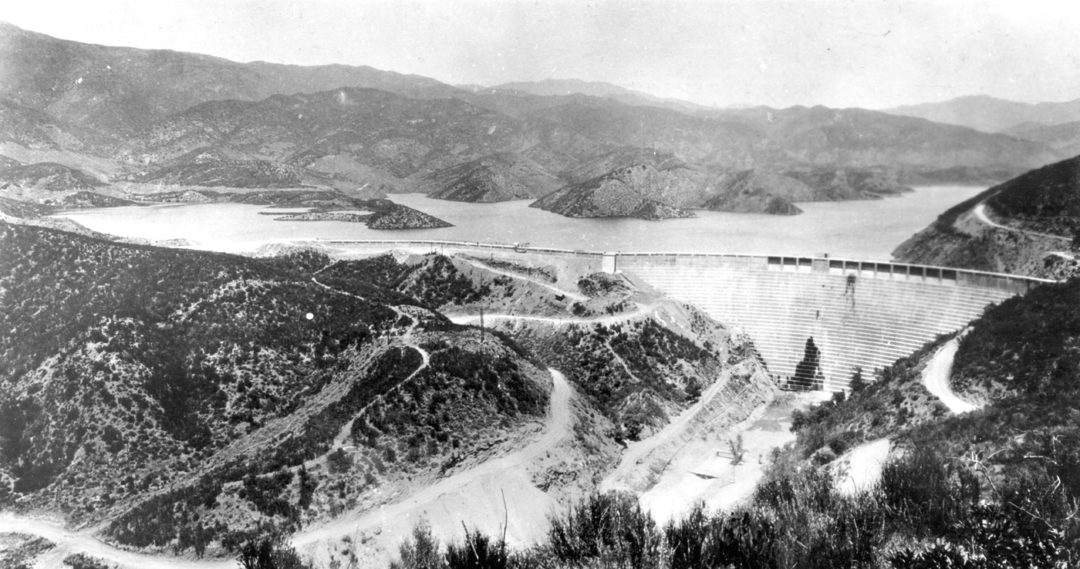

Construction on the dam began in 1924, and it officially opened in 1926. It was built under the direction of William Mulholland, general manager and chief engineer for the Los Angeles Bureau of Water Works and Supply. Mulholland was an instrumental figure in the building of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, which brought precious water—and the people drinking it—to the semi-arid city. Like the Los Angeles Aqueduct, the St. Francis Dam—located in San Francisquito Canyon, 40 miles northwest of Los Angeles—created a much-needed reservoir for the city’s precarious water supply.

Cracks and minor leaks were to be expected in a dam as large as the St. Francis, which rose up nearly 200 feet from the canyon floor. But on the morning of March 12, 1928, dam keeper Tony Harnischfeger reported a different kind of leak. Concerned that the brownish runoff could be a sign that the dam’s foundation had eroded, Harnischfeger alerted Mulholland, who arrived with his assistant chief engineer Harvey Van Norman.

After a lengthy inspection, Mulholland and Van Norman concluded that the dam was safe and left for Los Angeles. Just a few hours later—at approximately two minutes before midnight—the dam broke into pieces and released more than 12 billion gallons of water, killing all eyewitnesses, including Harnischfeger.

The 120-foot-high flood wave traveled 52 miles at up to 18 mph and destroyed everything in its path, including power lines and people. After plowing through several towns, the water—and everything it had picked up along the way—finally reached the Pacific Ocean. Bodies, if they were found at all, were discovered as far south as Mexico.

Several investigations were launched immediately following the disaster to determine its cause. A commission appointed by then-California Governor C. C. Young analyzed the dam’s construction and surrounding geological factors, reporting that the design was generally considered safe and the materials used were of “satisfactory quality and adequate strength.”

“There can be no question but that such a dam properly built upon a firm and unyielding foundation would be safe and permanent under all conceivable conditions, except perhaps faulting and earthquake shocks of tremendous violence,” the report states. “Unfortunately, in this case the foundation under the entire dam left very much to be desired.”

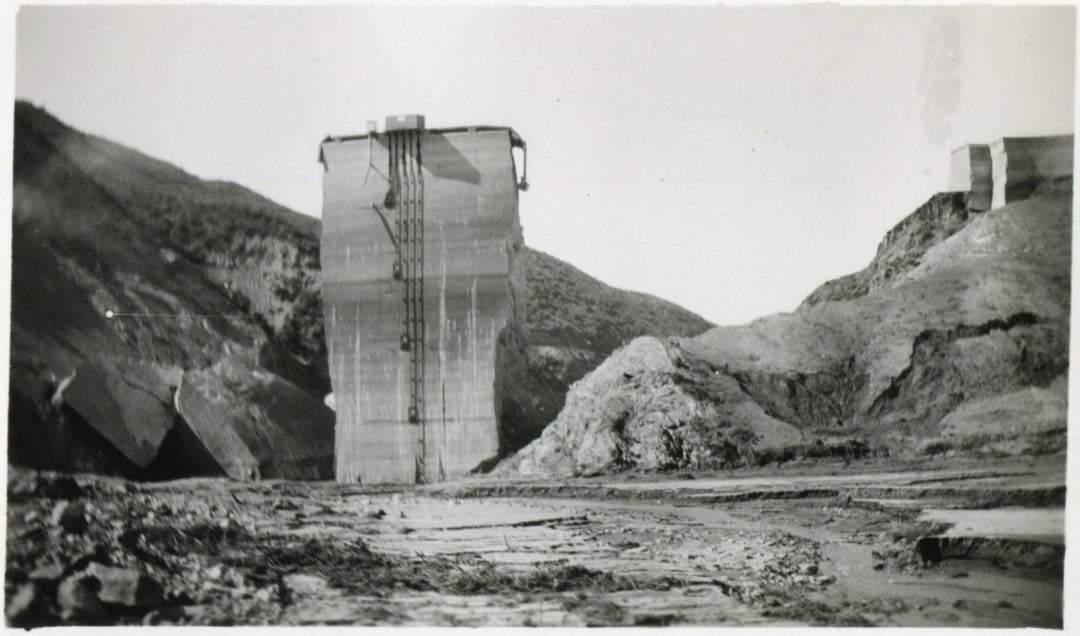

Samples taken from the ground underneath the dam proved that “the ultimate failure of this dam was inevitable, unless water could have been kept from reaching the foundation.” A still-standing portion of the dam that had been built on “reasonably sound bedrock” added to the conclusion that, above all else, “the failure of St. Francis dam was due to defective foundations.”

A few months after the disaster, the official death count was 385—but new victims were still being discovered as recently as the 1990s. At the Coroners’ inquest, Mulholland insisted that he had not discovered anything of concern on the day of the disaster, but he nonetheless assumed responsibility for the dam’s failure.

“The only ones I envy about this thing are the ones who are dead,” he said during his testimony. “Whether it is good or bad, don’t blame anyone else, you just fasten it on me. If there was an error in human judgment, I was the human, I won’t try to fasten it on anyone else.”

At the end of the inquest, Mulholland and the rest of the Los Angeles Bureau of Water Works and Supply were deemed responsible for the dam’s failure, but cleared of any criminal charges. Another casualty of the disaster was Mulholland’s career—he retired just a few months after the inquest, although he continued to consult on engineering projects.

Dam monument

In addition to national parks, the U.S. currently has 129 protected national monuments. Areas can be added to the list by Presidential proclamation or Congressional legislation, and in March, President Trump signed legislation designating four new national monuments: the site of the St. Francis Dam disaster, Jurassic National Monument in Utah, the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home in Mississippi, and the Mill Springs Battlefield in Kentucky.

“This monument will serve as a reminder for generations to come of the profound consequences of a failure of infrastructure,” Senator Harris said after co-sponsoring Hill’s bill.

Today remnants of the enormous concrete dam—and its steel reinforcements—can be found spread throughout the more than 350-acre site. In 1978, the State Department of Parks and Recreation placed a commemorative plaque at the site of a powerhouse that was destroyed in the flood. Nature—the destructive powers of which were on full display on that fateful day in 1928—has been slowly reclaiming the site ever since.

In addition to commemorating the huge loss of life and property, the St. Francis Dam disaster site is an important reminder that left unchecked, the hubristic human desire to tame and conquer the natural world can lead to catastrophe. Many populous parts of the U.S. are improbably built upon the grandiose dreams of people like Mulholland—and the future of such places is perhaps more precarious than we’re comfortable admitting.

In his report, however, Governor Young was optimistic about our role in shaping the world around us. “As the future of California depends in a large measure upon the storage of water, and the construction of dams, it is gratifying to note that this report finds that such structures can be built with entire safety when due regard is paid to suitability of foundations and correctness of design,” writes Young “This is the great lesson of the disaster.”

If you go

Remnants of the dam can be found along the creek bed beside San Francisquito Canyon Road about five miles south of Green Valley. A visitor center and educational facilities will be built within the next three years.