What does a stone think about? This is one of several questions visitors are offered to reflect on at a new exhibition at Storm King Art Center, a sprawling sculpture park located in New York’s scenic Hudson Valley. The site-specific installation by artist Martha Tuttle is spread over 8 acres, and made up of boulders found on the grounds stacked with glass stones that catch the changing light of the landscape.

Storm King is built to accommodate monumental works. The vast outdoor museum is set on 500 pristine acres of meadow and forest in the Hudson Highlands, roughly 60 miles north of New York City. The museum is celebrating its 60th anniversary this year, which it was expected to mark with an online exhibition showcasing its archives and history. Then came the pandemic and lockdown, and the new archival show suddenly became central to Storm King’s offerings. Instead of opening in April, as it does most years, it moved all its programming online.

With its 500-acre area ideal for social distancing, Storm King was able to reopen to the public in July. The museum is operating at one-third its usual capacity and visitors must register in advance online for tickets. The museum building, on a hill at the heart of the park, which normally houses paintings and other small-scale works, is still closed. The tram that circulates the park, allowing visitors to cover a lot of ground without having to walk it, is not running. Bike rentals are suspended. The outdoor café is doing boxed lunches and visitors are encouraged to find a secluded spot for a picnic.

But visiting Storm King in 2020 feels like a return to something—not normalcy, per se, but a sense of harmony with the world. My family and I, who have been museum members for close to four years, visited the first week of the reopening, and came prepared with a packed picnic lunch. In the masked faces of those whose paths we crossed, I recognized the wash of peace and solace they felt, combined with the awe of being in the presence of very big art. I wasn’t surprised to learn that new memberships have surged recently.

“We believe in the power of art in nature to inspire us and support our physical and spiritual health,” says John Stern, Storm King’s president. “Since opening our season, we are delighted to once again offer our site as a place for visitors to reflect and relax.”

Changing seasons

Storm King was founded in 1960 by Ralph Ogden and his son-in-law, Peter Stern, John’s father. The two were successful industrialists, owners of a local company that manufactured construction parts, such as screws and fasteners. They’d originally envisioned a traditional museum to showcase Hudson River School paintings, but when they came across the sculptor David Smith’s modern works, which he displayed outdoors, they were inspired and their vision evolved. Ogden bought the first 300 acres of land that would become Storm King, plus 2,100 acres of the Schunnemunk mountain face, which sits across from the museum, to preserve the view.

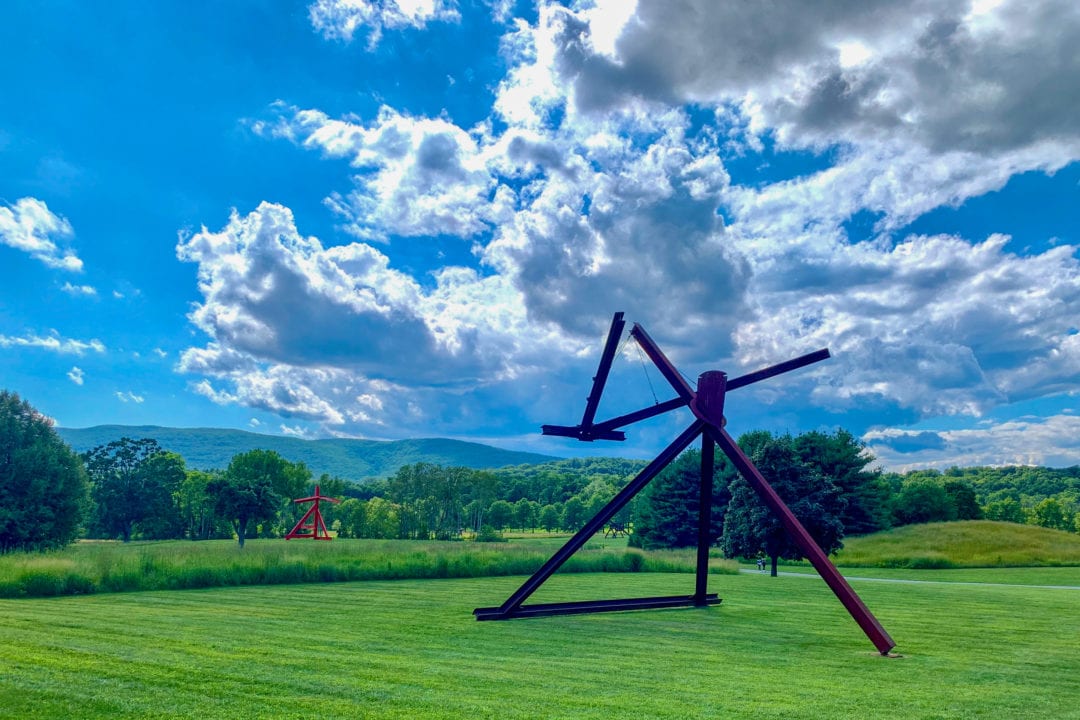

Many of the largest works at Storm King stand amid fields of wildflowers and native grasses that grow waist-high by midsummer and bristle with butterflies, bees, and dragonflies. The museum’s prolonged closure this year allowed the flora to reach impressive heights. Some of the most striking pieces are Mark di Suvero’s massive steel sculptures, painted jet black or bright red or left rough and rusty. They’re imposing and industrial-looking—the tallest stands 92 feet high—creating a stark contrast against the lush green background. Other works are hidden in wooded areas, like Patricia Johanson’s Nostoc II, a constellation of rocks down a rugged path that recalls the stone wall ruins hikers come across on trails in the area.

One of my favorites is Maya Lin’s Wavefield, made from a reclaimed gravel pit stretching over 11 acres that the artist shaped into grass-covered swells to look like waves. My daughter loves Zhang Huan’s Three Legged Buddha, a 28-foot-high steel-and-copper sculpture of the figure appearing to stand on his own head.

“Among the many things that make Storm King unique is that every visit is different,” says Stern. “The changing seasons, weather conditions, and even the time of day offer new ways to experience the art and surrounding landscape.”

Reflections

The Martha Tuttle exhibition is part of an annual series called Outlooks, which invites artists who have never worked in an environment like Storm King to create a site-specific work. The exhibition feels as if it speaks to the moment, but it was planned long before any events of this year unfolded. The work is titled A stone that thinks of Enceladus, a reference to a moon of Saturn that is one of the most reflective places in the solar system. Reflection is at the core of the piece: A placard accompanying the installation is printed with 22 brief statements and questions to reflect on as you make your way through it. They read as a sort of poem and, fittingly, the museum has created digital programming to accompany the exhibition that features poetry readings.

So what does a stone think about? I like to think a stone experiences time, the world, even us. It breaks down, unimaginably slowly, to become dust. Particles that might once have been stone, over millions upon millions of years, can accumulate to form new stone. If a stone thinks, I hope it looks at the world today and knows that this too will pass.