Just south of downtown Palm Springs, the rugged San Jacinto Mountains that fringe the city drop abruptly to the desert floor. This hillside pass, known as Tahquitz Canyon, was home to ancestors of the Agua Caliente band of Cahuilla Indians thousands of years ago. Today, the canyon is traversed by hikers, bighorn sheep, rattlesnakes, and the very occasional mountain lion.

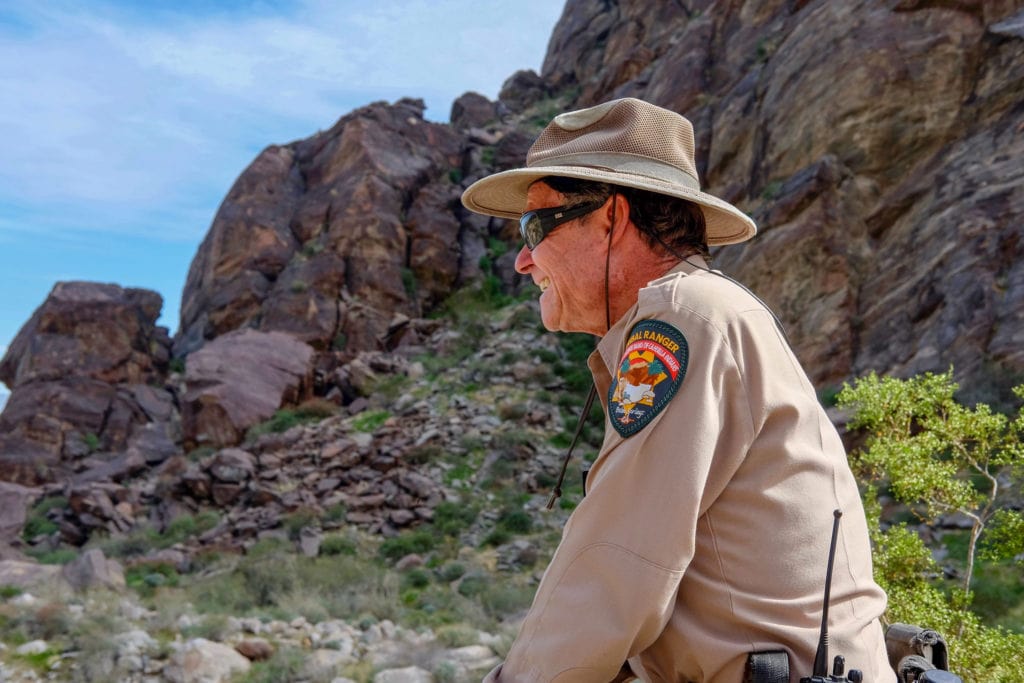

On a February morning, 70-year-old tribal ranger Robert Hepburn darts around this scrubby landscape, pausing in quick bursts to point out various native plant species growing along the path. A group of hikers follows along in an awkward clump, struggling slightly to keep up with Hepburn’s meteoric ascent up the canyon.

About an hour into the hike, Hepburn assesses his flock. “Did we get everybody up the hill?” he asks. “We did? Okay, good.”

Hepburn knows Tahquitz Canyon well. For nearly 20 years, he lived alone high up in the mountains, at an elevation of about 3,000 feet, in a log cabin he built by hand. The experience earned him local legend status and the nickname “Mountain Bob,” which still sticks, even in his second life as a tribal ranger.

In addition to his well-known moniker, Hepburn has been called many different things over the decades: a naturalist (according to a short biography in a book he authored), a hermit (in a Los Angeles Times article from 1999) and, now, a ranger. When I ask what he prefers, he says he calls himself an “adventurist.”

“I like adventure,” he says.

A secluded location

Hepburn first arrived in the California desert in the late 1960s. He was a Marine, back in the U.S. after serving in Vietnam and newly stationed at the base in Twentynine Palms, California. During a free weekend, he drove an hour to Palm Springs, where he was told he should hike to a waterfall in Tahquitz Canyon. Hepburn remembers being incredulous about the existence of a waterfall in the desert.

“I grew to love the area,” he says. A few years later, Hepburn bought three remote parcels of land, about 17 acres in total, above the canyon.

The location was extremely secluded—roughly a five-hour hike from the flatlands—and Hepburn would often go long stretches of time without seeing another person. He spent his time hiking, studying biblical languages (Hebrew, Greek, and others), gathering edible plants, and keeping an eye out for bobcats and mountain lions.

“But even up there I was watching the clock, so I would realize it’s time for lunch, time to study,” he says. Hepburn had a weekly routine of hiking into town to pick up odd jobs and buy groceries. “I’d call my work contacts and ask if they needed me that week,” he says. “If they didn’t, I’d get groceries and go back up. I always had a system.”

At first, Hepburn wasn’t planning on building an actual home for himself on the mountain; he merely built a floor a few feet off the ground “to keep out of the mud” and put a tent on top. Later, he used logs from the surrounding hillside to build a cabin. Other necessary items for the project—2x4s, cement, and saws—he carried on his back all the way from Palm Springs. Hepburn managed to lug up other personal items, too: a mattress, books, guitars, and miscellaneous pieces of furniture.

Hepburn and his cabin quickly became fixtures of the mountain, a novel landing place for intrepid hikers who made it that far up the canyon.

“You know, I had a cabin in an unusual place and hikers would see it and stop by,” Hepburn says. “That went on for many years.”

Tribal ranger

Shortly before Hepburn moved into the mountains, local law enforcement and Agua Caliente tribal leaders were grappling with an ongoing dilemma farther down in Tahquitz Canyon. Seasonal squatters and trespassers had taken over the area; they bathed in the falls, set up camp under ancient boulders, and left behind large piles of trash.

Newspaper headlines from the 1960s and ‘70s described the situation in grave terms. “Hippies Turn Canyon Into Filthy Pig Pen,” one read.

Tahquitz Canyon is owned by the Agua Caliente tribe, along with more than 30,000 acres of land dotted across the desert and mountains, making the presence of the canyon’s casual new residents illegal. In the 1990s, plans were made to finally evict trespassers and clean up the trash that had accumulated. The tribe also started building a modern glass-and-chrome visitor center at the mouth of the canyon.

Hepburn was soon enlisted to work for the tribe, starting as a member of the maintenance crew. After 18 years of solitude, it was time to come down from the mountains, he says. “I knew I was getting older and I needed to have some place down here to live. Eventually I ended up selling my land.”

In 1998, Hepburn and the rest of the maintenance crew started removing trash and telling squatters they had to find a new home. Soon, the Tahquitz Canyon visitor center opened, and eventually Hepburn became a ranger. In preparation to start giving tours of the canyon to visitors, each tribal ranger was given a topic to become a de facto expert on. “Native plants” was the last subject left, Hepburn says.

For the naturalist, scholar, and adventurist, it was an obvious choice. Hepburn gathered information, photos, and tribe-specific details about hundreds of local plants. “And it extrapolated into a book as the years went by,” he says.

The final product, Plants of the Cahuilla Indians, is considered to be a definitive field guide to the flora of the Colorado Desert and its surrounding mountains.

Hiking through Tahquitz Canyon

Today, Hepburn is officially one of three lead tribal rangers for the reservation. He’s now lived a more traditional existence (with a steady job and a home with electricity) for longer than he lived in the wilderness of the San Jacintos.

And he looks physically different, too. Photos from 20 or 30 years ago show Hepburn in weathered jeans, sporting an untamed beard, and a Davy Crockett-esque raccoon hat. At 70, he’s clean shaven and wears a crisp ranger uniform. A walkie-talkie, simple canteen, and binoculars are strapped to his belt.

On our hike, Hepburn is firmly in his element. He delivers rapid-fire facts about myriad plant life (honey mesquite, an unassuming shrub with twisted branches, was used to make bows and arrows, he says) and describes what life was like for the Agua Caliente Indians who once lived there. At one point, Hepburn points out a constellation of red-hued pictographs spread across one towering rock. The drawings were made 1,600 years ago with a mixture of iron oxide deposits and egg whites or animal fat, he explains.

But with all the cultural and botanical importance of this area, the canyon’s main trail becomes, at certain points, congested with visiting hikers. It’s a far cry from the isolation Hepburn sought several decades ago.

Despite the chaotic foot traffic, the 70-year-old offers a chipper greeting to at least half a dozen people walking by: “Great day, huh?” Working as a ranger is something of a reward after getting to know Tahquitz Canyon so well from his former mountaintop cabin.

“Visitors come here from downtown with all the problems of life—the traffic and the mortgage and the job and all those things—and they come here wanting a release and to experience something and learn something new,” Hepburn says. “So it’s very enjoyable to take them out on the trail. It’s very rewarding.”

If you go

Due to the spread of COVID-19, many points of interest are currently closed and travel is not recommended. Please check with businesses directly for the latest information on hours, and follow your state and local guidelines. Stay safe!