“I don’t like turquoise,” says Joe Dan Lowry, curator of Albuquerque’s Turquoise Museum, as he opens the doors of the former mansion located a few blocks from Central Avenue, or Old Route 66.

His statement catches me off guard. It apparently caught his grandfather off guard, too, when at age 8, Lowry announced he didn’t like turquoise in the same way that his dad, grandfather, and great grandfather all did. Lowry, a fourth-generation turquoise miner, lapidarist, collector, and author, thinks the color of the stone is too “loud.”

“But I love everything else about it,” he says, referring to the science, the history, and the passion his family, other miners, artists, and collectors have for the blue-green stone. Lowry’s deepest love is not for the mineral itself, but for the people who love turquoise.

His family has mined the Southwest’s turquoise, collected turquoise worldwide, traded Native American jewelry, and even designed bolo ties for astronauts on the Space Shuttle Columbia. As an turquoise expert, Lowry shares all the things he loves—and doesn’t love—about the gemstone with visitors at the museum his family opened in 1993.

Five generations

Portraits of five generations of Lowry’s family—including his children—hang in the museum’s foyer. Two stories above, a Swarovski crystal chandelier made with 21,500 turquoise beads hints at the elegance and unexpected treasures of the museum’s collection.

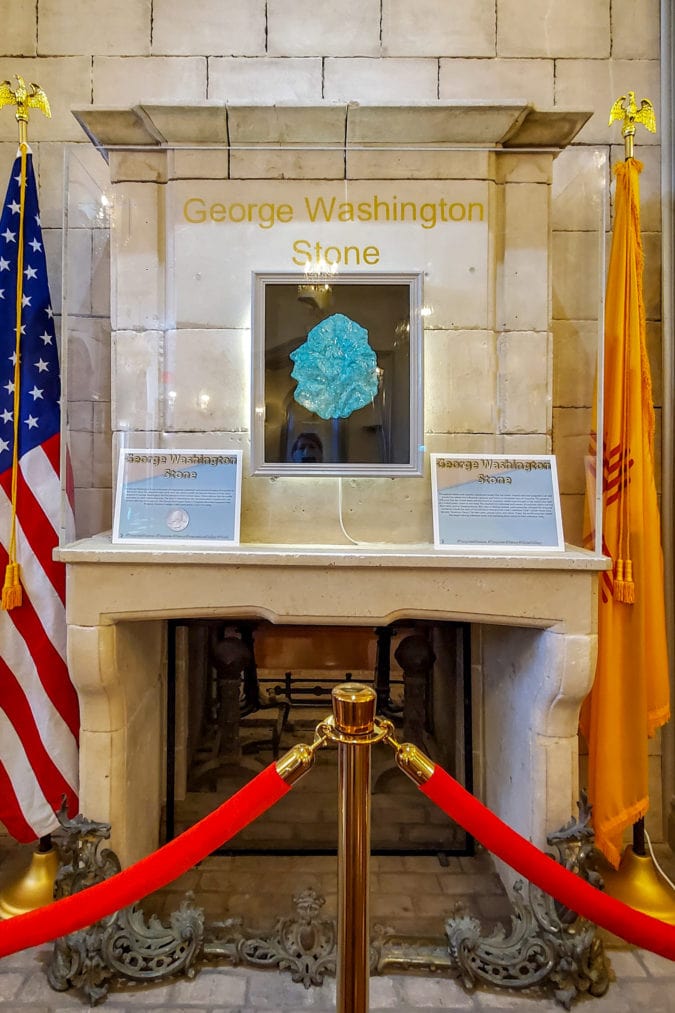

As I enter the Global Gallery, my preconceived notions of turquoise as a kitschy souvenir of the Old West are immediately dispelled. The gallery contains 15 pieces of turquoise that run the gamut in terms of size and intended use. The most famous is the George Washington Stone, a 9- by 11-inch 6888-carat piece cut and polished by Lowry’s grandfather. Originally destined for Lowry’s grandmother’s cedar chest, the piece looked too much like the first president to be kept out of the public eye.

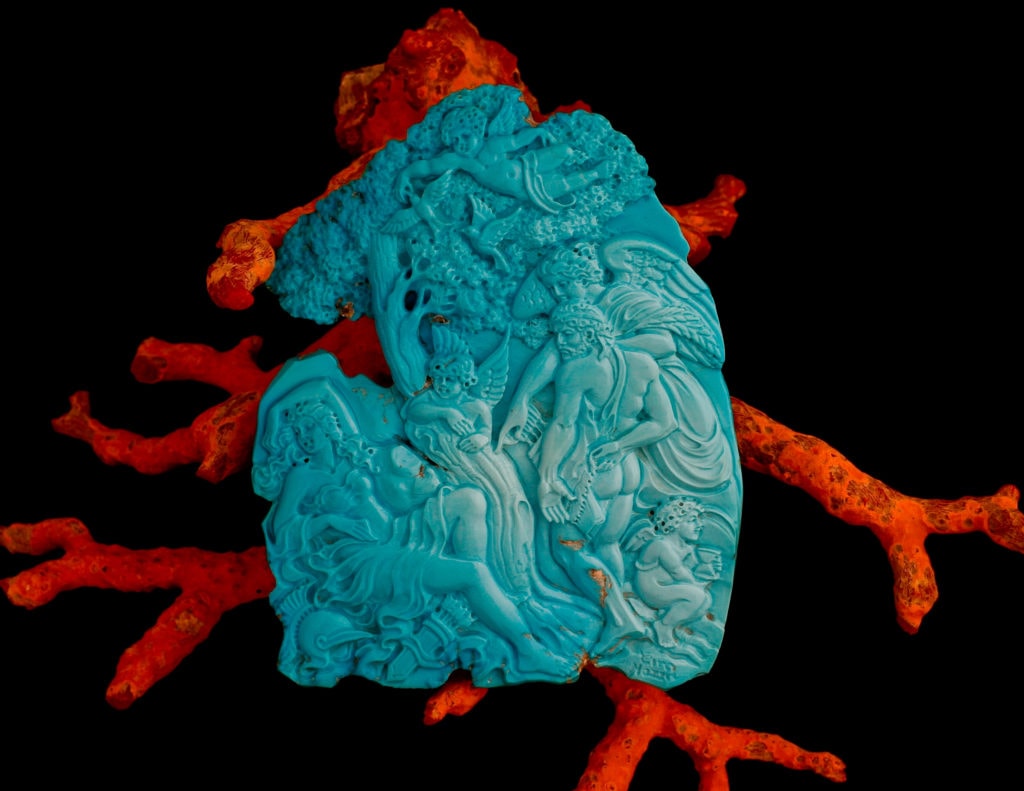

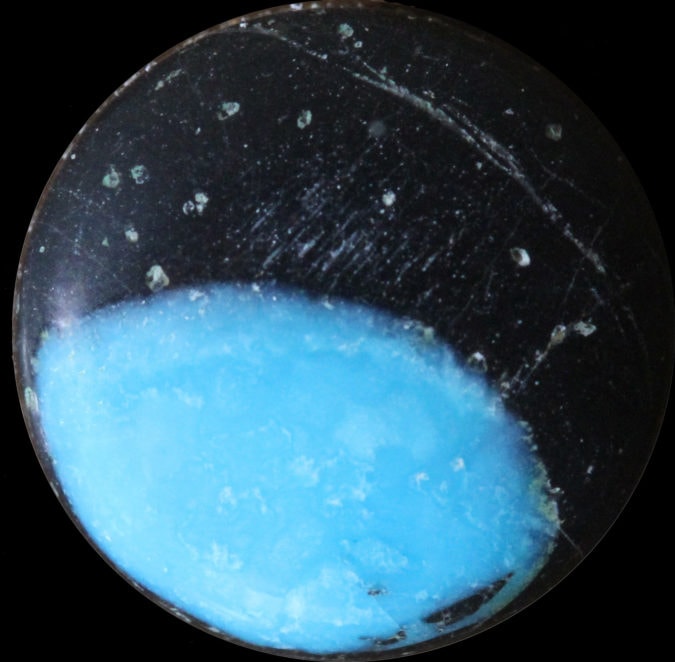

An intricate carving of Hercules and Deianira took six months to complete. The tiniest piece is a dime-sized stone cut by Lowry himself, a turquoise nugget on the edge of black stone resembling the first photo of Earth captured from space.

A rare mineral

The museum focuses on educating visitors about turquoise, including the mineral’s rarity. Lowry points out that almost any mall in America has a jewelry store selling diamonds. “How many turquoise stores are in every mall in the world?” he says. “Turquoise does not bow down to the diamond.”

A diamond is symmetrical, orderly, and universally rated by cut, clarity, color, and carats. Turquoise is anything but orderly. The color and matrix (the lines that run through the stones) make each piece unique. “It parallels life, culture, beliefs, and the uniqueness of every person in our world,” Lowry says.

The Turquoise Museum’s collection is likely the world’s largest, containing stones from more than 90 mines on six continents. An entire gallery is devoted to imitation turquoise that looks real enough to fool all but the most educated of eyes.

Tiffany’s turquoise

Eighty-five of the mines that have stones on display in the museum are located in the U.S. Southwest. Many opened in the late 1800s, when Persian blue turquoise soared in popularity. Fifth Avenue jeweler Tiffany & Co. struggled to keep up with the demand for the stone; its popularity is one reason why the company adopted the robin’s egg blue color as its signature hue.

But the mines in the Southwest produced turquoises in blues and greens lined with spiderweb matrices. This variety has always been special to Native Americans, who have used it for jewelry and in ceremonies for more than a thousand years. The stone is believed to possess healing properties and protect its wearer.

As travelers ventured to the West on passenger trains, they discovered Native American-made turquoise jewelry. The demand only increased as road trips along Route 66 gained in popularity. For the last 100 years, Native American turquoise jewelry has dominated the scene. The Turquoise Museum displays a treasured healer’s necklace as well as an extensive collection of jewelry handcrafted by Native American artists.

An international stone

On the other side of the world, the Ancient Egyptians mined turquoise and created objects inlaid with the stone intended for the afterlife. In current day Iran, the mining of turquoise began more than 6,000 years ago and yielded Persian blue turquoise that was brought to Europe via the Silk Road.

The museum’s International Gallery shows these trade routes and samples of turquoise mined around the world, including a 55-pound Iranian nugget gifted to the Turquoise Museum. Nearby, a painting of a Croatian king shows him wearing a turquoise belt and necklace. Looking at the portrait, Lowry says, “I’ve been looking for these pieces and haven’t found them—yet.”

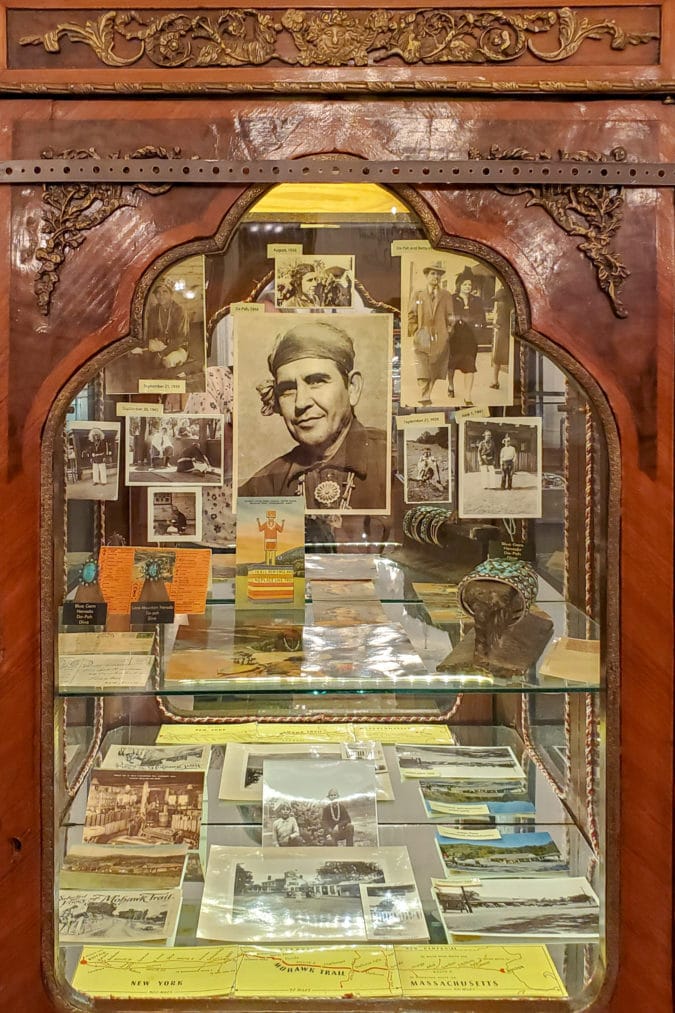

For Lowry, it’s not about the turquoise, but rather the relationships he builds because of it. Connie Lyon met with Lowry one day to have her mother’s turquoise jewelry appraised. She hoped he’d buy it for the museum. But Lowry was also interested in the story behind the stones.

When Lyon’s brother George Andrews was 14, he met Da-Pah, a famous Navajo silversmith. A trading post in Massachusetts had hired Da-Pah to craft turquoise jewelry and Andrews introduced him to his and Lyon’s mother, Betty. Their friendship continued, and when Da-Pah returned to his home in New Mexico, Betty followed. Their correspondence and the bracelets Da-Pah made for Betty (she wore them every day for the rest of her life) fill a case in the museum.

“[Connie] just wanted her mom’s story to be told,” Lowry says, “and I’m a storyteller.”

If you go

Guided tours of the Turquoise Museum are by appointment only. Visit the museum’s website for details.