This spring, I took a road trip from Ohio to Arizona and back to the East Coast, a 22-day journey across dozens of states, landscapes, and cultural climates. Instead of seeing states united, I emerged from the driver’s seat after more than 6,000 miles with something I can only describe as emotional whiplash. In a country still famous for its vast swaths of open space, it’s always surprising to me just how much the past, present, and future seem to all crash into—and overlap with—each other. Progress is palpable, but it’s also patchy.

In Montgomery, Alabama, the First White House of the Confederacy sits just a few hundred feet from the state’s capitol, where Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a sea of civil rights marchers from Selma in 1965. Further south in Louisiana, along a stretch of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans known as “Cancer Alley,” antebellum mansions are meticulously maintained alongside battered trailers covered with tarps. Chemical plants poison the air, climate change strengthens the storms, and gaps in wealth and social services have always threatened to fracture our fickle union; the farther I drive, the problems become easier to see—and seemingly harder to solve. Allegiance to anything comes with its own unique set of complications, but it’s always been hard to leave your home and change your mind.

Several roadside relics of the Confederacy have survived the most recent racial reckoning in the U.S., and others have not. Residents on Northern Virginia’s Plantation Parkway will soon have to change their mailing addresses, and all that’s left of Charlottesville’s Robert E. Lee statue is a bare patch of dirt sprinkled with grass seed and straw. When I visited C’ville recently, it was too late to see the statue, and too early to see grass growing in its place.

5 one-tank road trips from Washington, D.C.

More than 250 years after Whitney Plantation was established in southern Louisiana, John Cummings, who described himself to the New York Times as “a rich white boy,” chose to reckon with his property’s complicated past. In 2014, the former indigo, rice, and sugar plantation opened to the public as not just another fancy Southern house tour, but as a museum with a mission. At any given time during its run as a working plantation, Whitney was home to anywhere from 20 to hundreds of enslaved people. Today, the museum’s visitor experience is curated to ensure that you leave carrying at least some of their stories back to wherever you came from—even if it’s just down the road (admission for residents of nearby St. John and St. James parishes is free or discounted).

Redefining a relic

As a modern inhabitant of a country founded on stolen land and built with forced labor, I have a choice to make: Do I rest on my privileges and remain a relic of the past or join the reckoning? Whitney Plantation Museum has shown it’s possible to do the latter—without scrubbing the property’s painful history to a more palatable shine. Billed humbly as “the only former plantation in Louisiana to focus exclusively on slavery,” the New York Times went further in 2015, declaring it “the first slavery museum in America.”

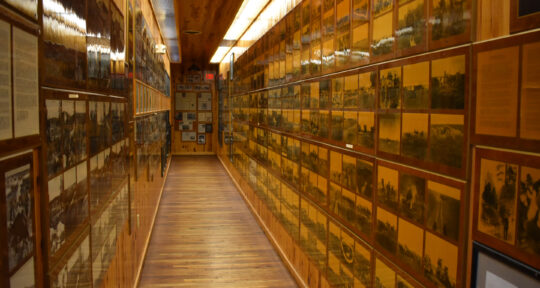

Visitors are encouraged to explore the grounds—dotted with structures, sculptures, educational exhibits, and memorials—at their own pace or accompanied by a comprehensive 1.5-hour audio guide (available for free via the museum’s app), or by joining a guided tour. Permanent exhibits include an overview of the transatlantic slave trade and another focused locally on enslaved Louisianans.

By the time the international trade of enslaved people was outlawed in the U.S. in the early 1800s, there were already nearly 20,000 enslaved Africans in Louisiana, with several thousands laboring in the region around New Orleans along the Mississippi River. Sugar eventually replaced indigo as the area’s dominant crop, and in 1803, the Louisiana Purchase flooded the territory with free labor, helping to make it one of the country’s wealthiest districts (known as the German Coast for the lineage of its land-owning occupants).

Language changes over time just as much (or as little) as the people who speak it. It may be negatively affecting real estate values in an upscale Virginia suburb, but the word “plantation” is still the second most used word in Southern Airbnb listings, used to conjure positive images of gilded, Gone With the Wind-esque grand homes. At Whitney, the “Big House” may have been conceived as the property’s centerpiece, but today, the focus is not on the Haydel family, who lived in the white three-story home ringed with columns for almost a century, but on the hundreds of enslaved people who labored inside and outside of it.

The Big House

Anna was an enslaved domestic worker who was separated from her family, gifted from one Haydel to another, and impregnated by her owner’s brother. Hers is just one of hundreds of very real horror stories the museum challenges visitors to absorb. One pervasive myth is that people working on seemingly-idyllic plantations or inside palatial residences were somehow spared the worst of a system unapologetically built on buying and selling human beings.

“Many people believe that it was better in some way to be an enslaved domestic, to work inside of the house, or that those people enjoyed some higher status,” says Ashley Rogers, executive director of the Whitney Plantation Museum. “They occupied a different space, to be sure, but enslaved domestics, unlike field workers, had to be not only working around the owners constantly, but also living near the owners constantly … The bottom line is that all enslaved people are kept on the plantation against their will, so there is no better or worse place to be.”

True to its nickname, the Big House is much larger than the ramshackle cabins occupied by enslaved laborers, who far outnumbered the owner’s family. Plantation houses were constructed not to be practical, but to be purposefully grandiose as a means of conveying wealth to passersby. In some cases, like at Whitney, the mansion’s outward grandeur doesn’t extend to the interiors, which are sparse and more utilitarian than visitors may be expecting.

It’s a purposeful illusion: Exterior flourishes, including columns, wraparound porches, and two brick roosting houses for pigeons, were “meant to be decorative and to be communicative about the wealth of the plantation owner,” says Rogers. “These would be very fashionable at the time, and so anyone who drove by in a carriage on the River Road, if they could see it from a boat on the Mississippi, they would know that this was a significant plantation, owned by wealthy slave owners.”

Cycle of debt

Although it was profitable, sugar was an especially punishing crop to produce and the dangers faced by workers tasked with planting, harvesting, and refining it were all too real. According to the museum, “The sugar districts of Louisiana stand out as the only area in the slaveholding south with a negative birth rate among the enslaved population. Death was common on Louisiana’s sugar plantations due to the harsh nature of the labor, the disease environment, and lack of proper nutrition and medical care.”

In front of the Big House stands the plantation store, built in 1890. Workers—technically “free” for decades since the Emancipation Proclamation—bought food, clothing, and medicine on credit, often finding themselves trapped in a cycle of debt that inextricably kept them tethered to the plantation well into the 20th century. After MLK was assassinated in 1968, workers set fire to similar stores that still dotted the riverbank, including Whitney’s.

While most of the structures are original, others have been moved here to help tell a more complete story of the enslaved experience. A jail was not a standard feature of a working plantation, but Whitney acquired an 1868 slave pen from Gonzales, Lousiana, offering visitors another chance to consider the lasting legacy of slavery—long after it had legally been abolished.

“Louisiana was consuming people at a really high rate,” explains Rogers. “There was a high death rate, so there’s a greater demand for people.” People treated and sold as property were confined by auction houses into metal pens divided into cells—the entire unit no bigger than a shipping container—and priced based on several factors, including reputation, skillset, gender, and physical attributes.

Fighting for freedom

Several sculptures and memorials seek to dispel the misconception that enslaved people rarely fought for their freedom. A macabre memorial to the participants of the German Coast Uprising features rows and rows of decapitated heads. Over 2 days in 1811, hundreds of enslaved people, organized and led by slave-driver Charles Deslondes, fought back against plantation owners. The rebellion was quickly overpowered by the well-armed local militia, and its leaders’ severed heads were displayed on pikes along River Road as a warning to anyone considering a similar revolt.

One sculpture, Returning the Chains, depicts a larger-than-life hand, rusty and ripped at the wrist, tugging at an oversized length of chain link; it is both free from its body and still tightly grasping its shackles, which remain stubbornly stuck in the ground. Nearby, the Wall of Honor lists the names of all the enslaved people known to have worked at Whitney, interspersed with first-person narratives collected as part of the WPA Federal Writers Project in the mid-1930s; the sprawling monument is both painstakingly detailed and woefully incomplete.

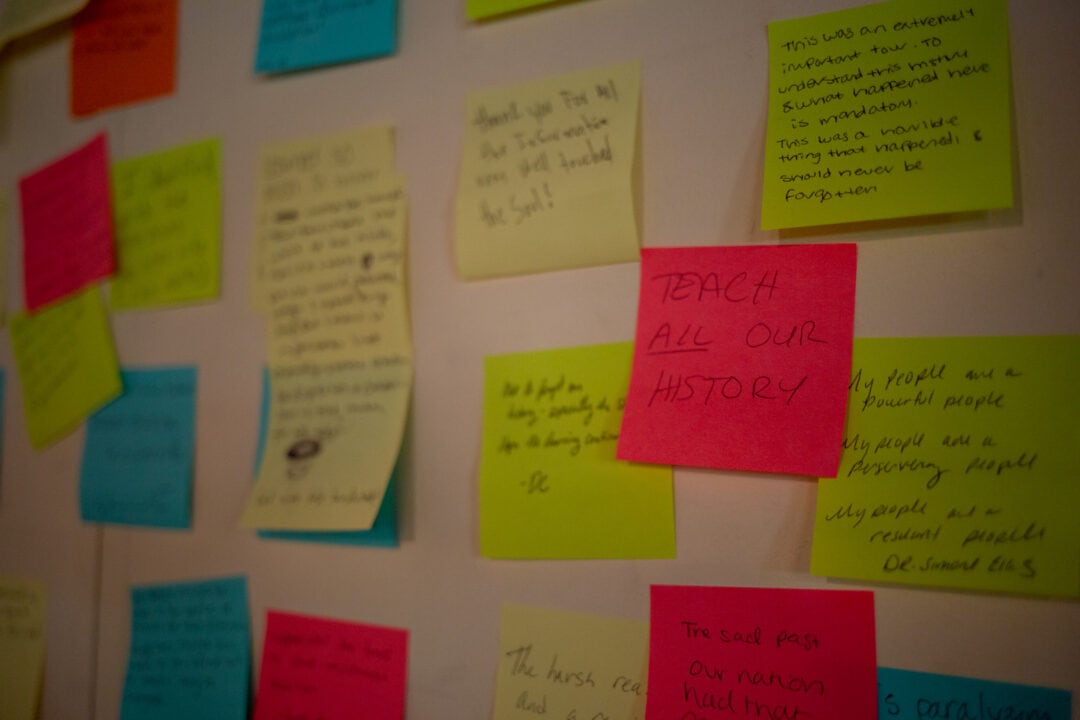

Upon exiting, visitors are encouraged to reflect on their experience via Post-it notes stuck to a white half-wall in the modest gift shop. Each colorful square represents another story worth sharing, the sentiments as diverse as the people who wrote them: “History is more than a textbook” and “I am my own wildest dream.”

One thing is notably absent from the Whitney Plantation experience: I have learned very little about the plantation’s white owners and their descendants, and I know that’s the point. The story of white America has been told and retold throughout centuries, decorated and elevated to convey grandeur, but it’s only ever been half the story, if that; both as real, and as deceptive, as the Big House.