Once upon a time, natural springs hidden among the rolling hills of southern Indiana flowed with waters said to revive health and wellness with a mere soak and a few sips. Beginning in the mid-19th century, visitors across the U.S. poured in by train to West Baden Springs and French Lick, two neighboring Indiana towns, hoping to benefit from the purportedly curative “Pluto Water.” Many of them stayed at the magnificent West Baden Springs Hotel, a resort that boasted seven springs on its elegantly landscaped grounds, where visitors could bathe and drink the magical waters that promised to cure everything from depression to diabetes.

13 activities and events perfect for celebrating fall in the Midwest

Alas, these waters held a sinister secret: a high native dose of lithium, a potent drug used today to treat major depressive disorders, and a high content of sodium and magnesium sulfate, minerals that caused a forceful laxative effect after ingestion. And while visitors can no longer indulge in the mighty Pluto Water—which was banned for consumption in 1971 when lithium became a controlled substance—the West Baden Springs Hotel still stands as a majestic, vibrant souvenir of America’s Gilded Age.

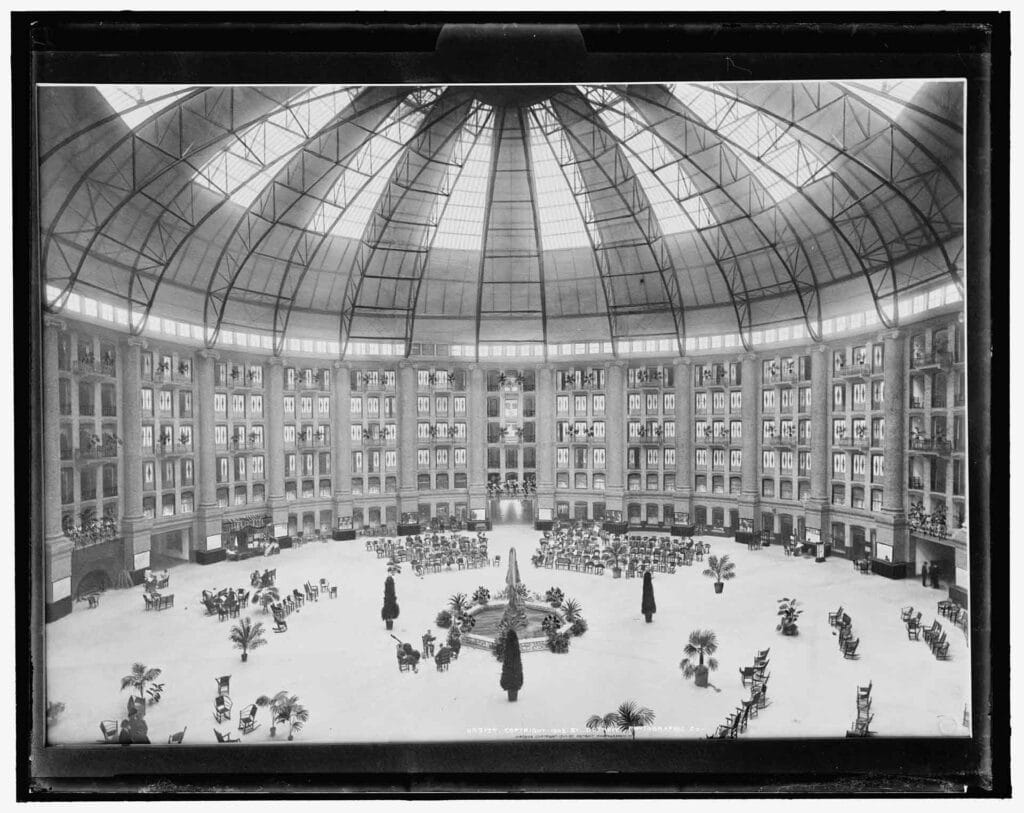

With its massive, 200-foot dome—the largest in the world when it was built—the West Baden Springs Hotel was once considered the eighth wonder of the world, in a town known as the Carlsbad of America. While its sister resort, French Lick Springs Hotel, is often described as one of the most haunted hotels in the U.S., the West Baden Springs Hotel has legends of its own.

Crime novelist Michael Koryta visited the then-abandoned resort with his family when he was 8 years old. He was so intrigued by the crumbling ruins that the fateful visit inspired a love of history and, eventually, a novel. His bestselling thriller, So Cold the River, follows a documentary filmmaker who travels to West Baden Springs to investigate the dark secrets of a dying millionaire resident of the resort. His research leads him to discover an evil force that still flows around and under the hotel. The 2022 horror movie adaptation of the same name was filmed on location in the winter of 2020.

From salt lick to celebrated spa town

Roaming herds of deer, still known to wander the hotel’s grounds, once visited the salt lick located on the present-day site of the West Baden Springs Hotel. Native Americans arrived in the area via the adjacent Buffalo Trace, an ancient trail carved by migrating buffalo, and hunted the abundant deer. French traders settled the area in the 18th century and gave the area its name, French Lick.

In 1832, inspired by the local spring waters’ alleged healing properties, Indiana physicians Thomas Bowles and his brother William purchased 1,500 acres of land that included the mineral springs and eventually built the region’s first spa-centric hotel, the French Lick Springs Hotel. Yet another physician, John A. Lane, purchased the 770 acres just north of the hotel in 1851, where he built the West Baden Springs Hotel, named after the famous German spa town “Wiesbaden” and rivaling its southern neighbor in grandeur.

By the end of the 19th century, the West Baden Springs hotel boasted hundreds of guest rooms where guests stayed for weeks at a time, hoping to capture the healing power of the springs. Two fires near the turn of the century led to new construction and even more over-the-top amenities. By 1901, the resort had a casino, a theater that hosted a world-class performance every evening, a bowling alley, a billiards room, an elegant natatorium, two golf courses, and a double-decked oval cycling track centered with a baseball diamond.

Wild birds flew free among palm trees that lined the colossal atrium. An on-site bank and stock brokerage, which can still be seen today standing near the resort’s main entrance gate, made it easy for wealthy clients to keep up with the market and easily withdraw assets for gambling.

The resort boomed with wealthy and famous guests from across the U.S. Stars, including Harry Houdini, Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Lana Turner performed at the hotel theater. The Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus staged performances in the expansive atrium. Professional baseball players from the Cincinnati Reds, Chicago Cubs, and Pittsburgh Pirates spent their springs here, training on the diamond when they weren’t “taking the waters.”

The hotel’s roaring ’20s came to a halt with the stock market crash of 1929. By 1934, the beleaguered owner sold it for a mere $1 to the Jesuits, a religious order of the Catholic Church, who turned it into a seminary and sealed all the springs with cement. When the Jesuits moved on, the property housed a college for a few years. But by the 1970s, the once splendid hotel sat empty; deteriorating, its grandeur had seemingly disappeared into thin air. It wasn’t until Indiana Landmarks stepped in to stabilize the structure that it began to slowly return to its former glory. In 2006, the historic hotel reopened after a multi-million dollar restoration. Today, the more than 100-year-old luxury hotel bustles with guests once again.

The modern day resort

To see the mystifying Lost River, which emerges from a cave after traveling through a vast system of underground channels, hike the Orangeville Rise, a 187-acre National Natural Landmark dotted with sinkholes and concealed caves.

Today, the West Baden Springs and French Lick Springs hotels are no longer rivals, but equal parts of the French Lick Resort. Guests can once again experience the Gilded Age grandeur of both hotels and mingle with ghosts of the past. Here’s how to experience it for yourself:

Book a room with an atrium view

Peek out your window at night to see the center of the West Baden Springs Hotel’s dome, which is lit with color after sunset and casts an otherworldly glow into the grand atrium. When the hotel was renovated in the 1990s, workers discovered the Angel Room, a tiny cylindrical room at the top of the atrium just below the center of the dome. Its walls are lined with a series of mysterious oil paintings of angels.

Dine at 1875: The Steakhouse

Located inside the French Lick Springs Hotel, this restaurant was named in honor of May 17, 1875, the date of the first Kentucky Derby. Dinners here begin with a shot of tomato juice, because in 1917, the hotel’s chef de cuisine, Louis Perrin, invented the drink when he ran out of orange juice and needed a quick substitute.

Soak in the magical Pluto Waters of yore

You can still “take the waters” at the Spa at French Lick. Book the on-site spa’s Pluto Bath treatment and you’ll soak in the healing spring water in a circa 1920s tub. Expect a strong sulfur smell.

Hike the Buffalo Trace Trail

Hike a 5.8-mile segment of the Buffalo Trace, the trampled remains of an ancient buffalo path.

Sip a West Baden Bloody Mary at Ballard’s in the Atrium

Enjoy signature cocktails under the atrium’s grand dome in the bar named for Ed Ballard, who owned West Baden Springs Hotel during its 1920s and early ’30s heyday.

Set off on a horse-drawn carriage ride at twilight

Catch a carriage near the formal gardens and snuggle under a blanket as the horses carry you on the historic brick road that connects the two grand resorts. You’ll pass by a cemetery that forms a “Z” on a hillside just southwest of the West Baden Springs Hotel: Thirty-nine priests who died during their tenure at the building were buried here, including the Jesuit seminarian believed to have painted the murals in the Angel Room.