Imagine being chased by a blizzard while driving from Vancouver to Banff, Canada, running the gauntlet of crossing four mountain passes in winter. At each stage, the road behind us either became impassable or was destroyed altogether. Our 10-hour journey lasted 28 hours after snow, floods, mudslides, road closures, and more than 20 truck accidents turned the highway into a parking lot. We were 70 kilometers (43 miles) from home—on the final mountain pass—when we were forced to a halt.

I suppose undertaking a major road trip across the Canadian Rockies in winter was a bit risky. But then, my girlfriend Kathi and I are both skiers and experienced in driving in snow and ice; I used to live in the mountains, and she still does. Digging cars out of snow is de rigueur. We hadn’t banked on destroying the road behind us though.

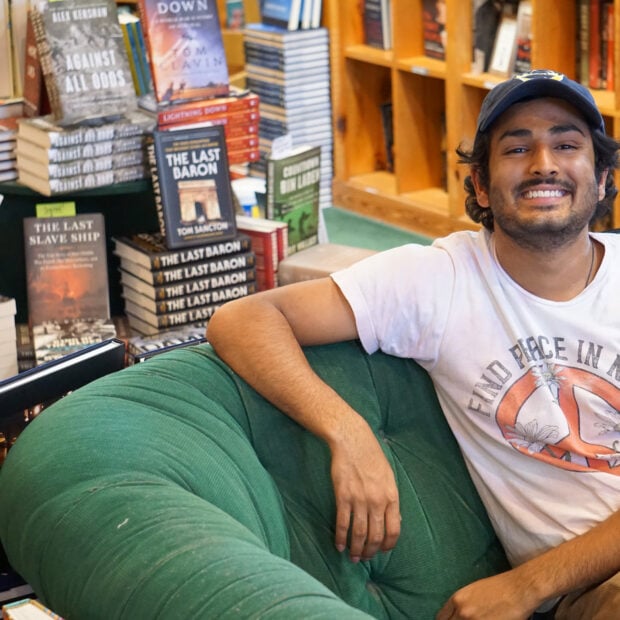

Driving the other direction to visit our friend was a dream. We broke the Banff to Vancouver journey halfway at Vernon, for a spa, wine tasting, and a hike. Vancouver was a healing tonic of friendship, sightseeing, dining, and laughter. As our date to return home approached, Kathi studied the weather. There was a storm coming, so she called it. We cut our trip short and planned to leave early in the morning on the following day.

Followed by chaos

The winter storm crept in with a whisper. We departed Vancouver as the mist, glowing in streetlights, turned to drizzle. By Abbotsford we were hydroplaning. The first section of the Trans-Canada Highway runs near the U.S. border, through the Sumas Prairie and along the Fraser Valley to Hope. It’s very flat, and we had to get higher before it flooded.

Gale-force winds knocked out electricity for 30,000 people. Flooding in the Fraser Valley caused more than $1 billion in damage to property and infrastructure, and killed more than 600,000 livestock. Officials called it the “storm of the century.”

The Coquihalla Highway is so dangerous it’s nicknamed the “Highway to Hell,” and has its own TV show. Running more than 500 kilometers from Hope to Tête Jaune Cache, it treats vehicles with as much respect as a child throwing a temper tantrum. We drove gingerly. Although visibility was poor, thankfully the rain hadn’t turned to snow.

Hours later, the Coquihalla snapped in two. As the only national transportation corridor, Vancouver’s road access to the rest of Canada was cut off for 5 weeks. The highway took 10 months to be fully repaired.

Conditions after the Coquihalla Summit were surprisingly different. The rain stopped and the monochromatic brown landscape looked like a desert. We risked a quick breakfast to-go at Merritt. But hours later Merritt suffered significant flooding; the sewage treatment plant failed and the entire town had to be evacuated.

Ignorance is bliss. Perhaps we could outrun it, we thought. There were four major mountain passes to cross, and we nervously checked them off. One down. We made it to Kamloops before the snow caught us. We slithered into Revelstoke. Two thirds of the way home. Breathe.

As we climbed over the Rogers Pass to Golden, speeding drivers were overtaking in dangerous spots. The road conditions wouldn’t support such bravado, so many were punished. Cars spun out, 18-wheelers jackknifed. The litany of broken semis and stationary vehicles was astonishing. Some stopped in the middle of the road to put on chains. Others were in the ditch, some overturned, others with flat tires or a broken axle.

Two passes down, two to go

At this point, the Trans-Canada Highway was closed for construction. Instead of driving Golden to Banff directly, we were diverted to Radium Hot Springs. Unfortunately, this added 100 kilometers to the journey. No problem, right? We’d survived so far and were almost home.

In Radium we started up the mountain pass. The traffic was unusually heavy. The road was jammed as far as we could see, and we sat for 45 minutes, not knowing what was going on. By this stage I was wearing my ski gear and hopped out of the car to canvas other drivers.

When things go wrong, quite often the first thing you need is information. On this route we had no cell phone access, no WiFi, and no gas stations. Kathi suggested I ask a trucker, so along the highway I trudged, knocking on car windows and climbing up to the cabins of big rigs. The first trucker couldn’t understand me. The second told me that their CB radio didn’t work. The third also said his radio was faulty, but he heard a semi had broken down and it would be a 4-hour wait. I shared what we knew with others. There was great camaraderie among us.

With 120 kilometers to go and 170 kilometers of gas in the tank and a full battery, we wondered if we should turn back to Radium to find a hotel. By all accounts, all accommodations were taken. Besides, I had an international flight to catch.

As the car inched forward, we quickly ascertained it would be a fight between fuel and battery. Since we were both well-dressed and warm, Kathi turned off the headlights and ignition each time we stopped.

Now 90 kilometers to go and 120 kilometers of gas with 95 percent battery. As the pass was still open at each end, more drivers joined us—with nowhere to go. Aggressive vehicles created a second lane on the single-lane highway; 18-wheeler trucks inched and slithered closely past each other, swaying in the deep rutted snow so badly the tops of their cargoes almost connected; cars jostled and maneuvered to create a third lane, but vehicles were still driving at fairly high speeds in the opposite direction. Overtake at your peril.

A nocturnal alpine traffic jam

With 80 kilometers to go and 100 kilometers of gas with 80 percent battery, we had moved forward 200 meters in 2 hours. It grew dark. Lit by headlights, the alpine forest glowed like a Christmas card. We took stock of our food—salami, cheese, water, and a case of wine—and settled in for the night, putting on hats and gloves. Lying down in the back seat, there was a big rig right by my head; its front wheel was higher than me, and it made us feel like we were sleeping beside a building. Kathi, still sporadically inching forward, prudently slept in her driver’s seat.

We were completely stationary from 11 p.m. to 6:30 a.m., which was fortunate as we could actually stop and sleep. I idly wondered whether the outside world realized we were stuck, and how long it would take to clear the jam. Falling asleep, I triaged how long our food could last.

Waking at first light, we ate some salami and cheese. Cars ahead of us inched forward and Kathi tried the ignition. There was an ominous click—the battery was dead. We had been on the road for 25 hours, driven 840 grueling kilometers, and were close to home—and now stuck.

No sooner had our hearts sunk than a pickup stopped to offer help. It took less than 30 seconds for assistance, and we were on our way within 5 minutes. It was heartening to see people help each other in a crisis.

Running on fumes

Mercifully the stops and starts lessened. Kathi still cast an anxious eye on the dashboard, watching the fuel click down: 60 kilometers to go with 70 kilometers of gas; 50 kilometers to go with 53 kilometers of gas. We crossed the Continental Divide and broke even, then we were negative. With 30 kilometers to go and only 27 kilometers of gas in the tank, the car shut off the countdown and turned the gas warning light on—we were operating on a wing and a prayer.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police finally closed the mountain pass, allowing the backlog to clear. You could see the barrier over the road on the opposite side, and we drove past miles and miles of stationary vehicles waiting to drive west. But for us, there were no more stops. The mountain pass connected back with the Trans-Canada Highway and it was a straight shot into Banff—we made it to Banff on fumes.

Despite our 28-hour journey we were safe, had some excellent conversations, and kept our spirits up. Kudos to Kathi for her incredible driving, wonderful positivity, and conquering a beast of a journey.

If you’re planning on taking a cold-weather road trip, here are some things we learned: Travel with hats, gloves, and clothes warm enough for you to stand outside your car. If you’re warm enough inside the car, turn off your car heater to save energy. Store reflective emergency blankets in your car year-round (they weigh nothing and take up very little space). Travel with food and water, and keep your gas tank topped off. Conserve gas and be mindful of your battery—or just don’t try to cross the Rockies in winter.