On my first trip to Alexandria, Virginia, in 2018, I was enchanted by the King Street shops and bustling waterfront restaurants in cobblestoned Old Town—and by the progressive Del Ray neighborhood where inclusive signs were posted in storefront windows and planted on lawns in front of colorful Victorian homes. It was more diverse than I expected and I recall thinking, “I could live here.”

About a 4-hour drive from New York City, Alexandria’s proximity to Washington, D.C., makes it an easy road trip. So in desperate need of a change of scenery, in mid-May I return to pedestrian-friendly Old Town—this time with my husband—just as face mask and social distancing restrictions are being lifted. During this visit, however, I get a closer look at Black life in Alexandria (both past and present) through walking tours and thoughtful conversations with several Black business owners.

Meet the people highlighting Richmond, Virginia’s rich Black history and hopeful future

From slavery to freedom

As we sit in Market Square waiting for John Taylor Chapman, a city councilman and local tour company owner, I remember snapping a selfie in this landmark spot on a balmy summer evening back in 2018. This time, with the square’s picturesque water fountain and huge American flag affixed to the City Hall building in the background, I watch as a young African American woman poses for college graduation photos, beaming in her cap and gown. Today it’s home to a bustling Saturday farmer’s market, but during the colonial period, Market Square was the site of slave auctions.

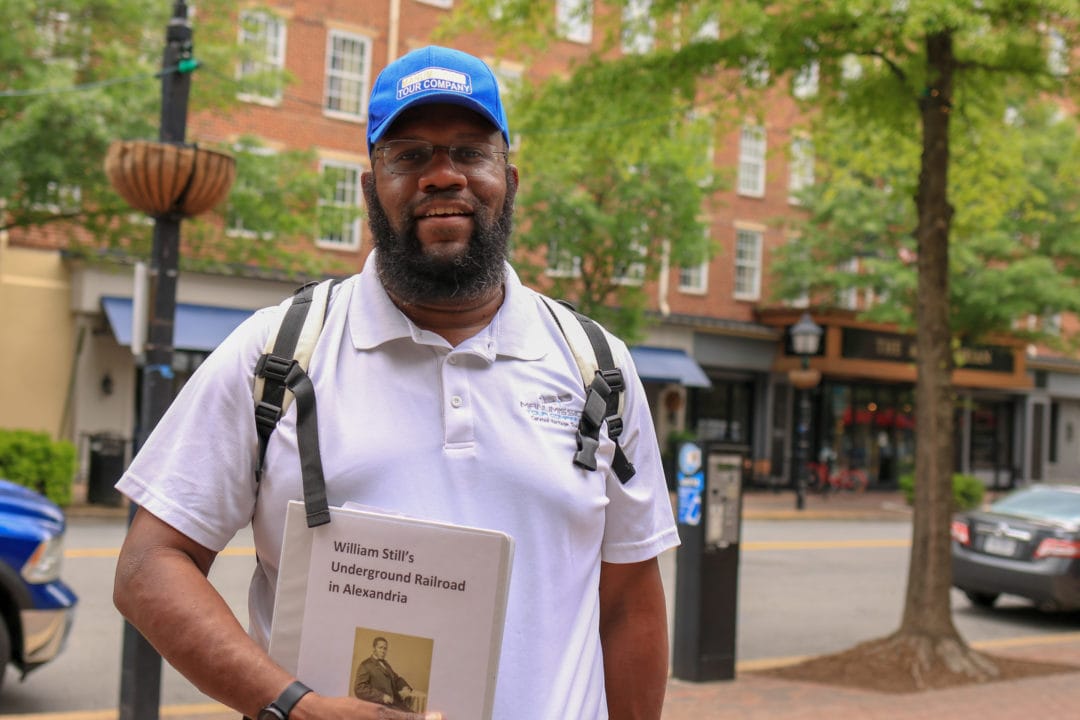

When he arrives, Chapman explains that there’s no plaque commemorating how our ancestors were bought and sold alongside produce and cattle in the town square. Those gaps in the city’s historical tourism offerings inspired the fourth generation Alexandrian to launch Manumission Tour Company (“manumission” means release from slavery).

“There really wasn’t a big discussion on Black history here when I was young,” says Chapman, who moved back home after he graduated from Saint Olaf College in Minnesota. “We talked about the early colonial founders, but African American history and slavery was never mentioned.”

To unearth Alexandria’s hidden Black history, Chapman crammed every day for several months at the Barrett Branch of the Alexandria Public Library. It was here in 1939 that a sit-in for equal access for African Americans occurred, and Chapman researched the lives of enslaved and free African Americans during a time when Alexandria was a hub of the domestic slave trade.

Manumission offers several 90-minute walking tours, including “Still’s Underground Railroad.” Based on abolitionist William Still’s 1872 book The Underground Railroad, the tour recounts the stories of several fugitive slaves from Alexandria and ponders who might have helped them on their road to freedom.

“It’s been an interesting journey,” Chapman says. “When I first started, I honestly learned something new every day. For me, the best part is having local folks come [on a tour] and learn the history that they’ve never known.”

Each one, teach one

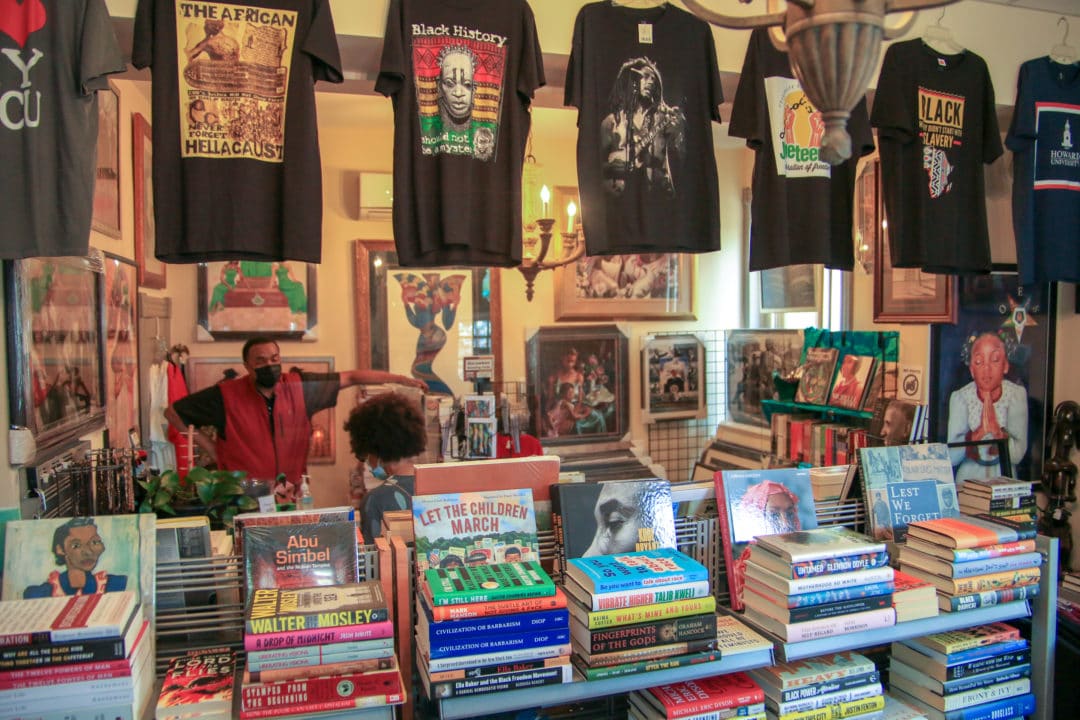

At Harambee Books & Artworks, an independent bookstore located on a quiet residential block in Old Town, owner Bernard Reeves invites us to look around and “check out the vibrations.”

While my husband takes photos, I make a beeline for the t-shirts with images and slogans paying homage to historical events like Juneteenth and historically Black colleges and universities, including my alma mater, Howard University.

With sandalwood incense burning, the retired Air Force officer explains that “harambee” means “working together” in Swahili. Reeves’ mission for the small-but-mighty bookstore—which specializes in rare and out of print books, children’s books, current bestsellers, and apparel and artwork by people of African descent—is to uplift and enlighten the community with cultural knowledge. Pre-COVID-19, Harambee hosted book signings and the annual Ujamaa Book Festival—events that he says will hopefully resume post-pandemic.

Growing up during segregation, Reeves was nurtured by his Black teachers. Following in that tradition, he started a literacy program with local barbershops to negate violence and encourage young Black boys to read.

“This is my way to give back,” he says. “As a young person, reading blew my mind and took me to places I never thought I would go.”

When they see us

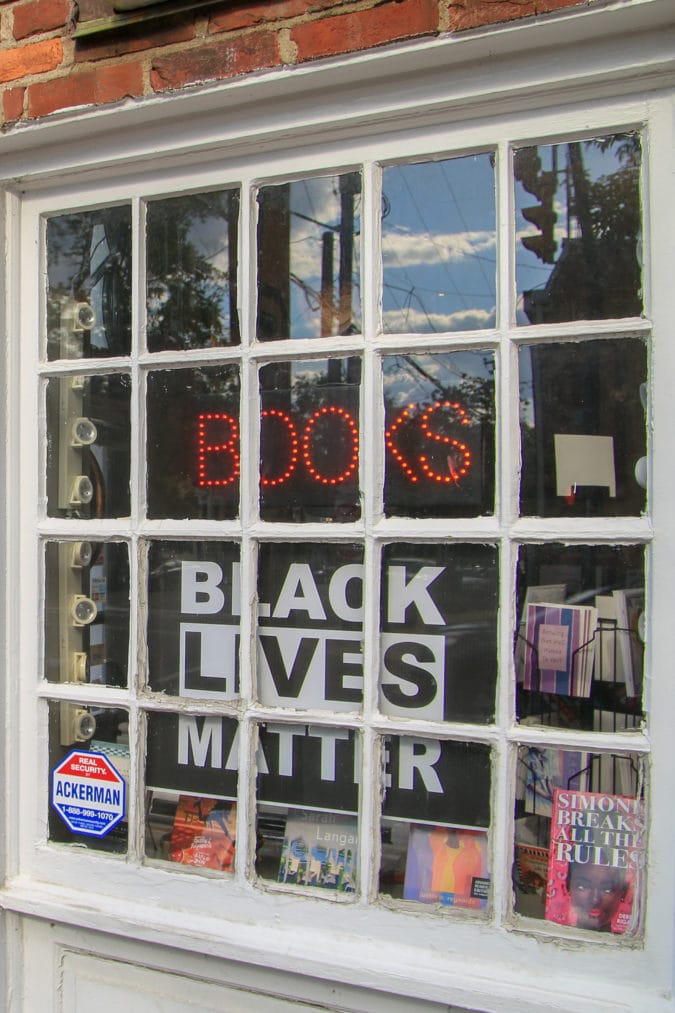

Black business ownership in Alexandria dates back to the 18th century. Currently, there are more than 20 Black-owned businesses in town, most of which have gained more visibility during the Black Lives Matter movement.

Nicole McGrew owns Threadleaf, an ethical fashion boutique in Old Town. “We’ve had Black people in Alexandria for a very long time, contributing and helping to build the city. Not enough people know [that history],” she says. “But I really wanted to be part of people recognizing that we’re here and we’re doing stuff.”

The former attorney for the Obama administration moved to Alexandria from Washington, D.C., in 2008 and opened her meticulously-curated sustainable women’s clothing and accessories shop in 2018. McGrew initially wanted to be a designer, but went into law because she once thought fashion was “frivolous.”

“I had this idea for a shop in my head for a really long time, and especially the more I learned about how polluting the [fashion] industry is,” McGrew says. “So then I thought, well, this will be a way for me to have my shop and combine all these other elements about environmentalism and labor practices.”

Goodies Frozen Custard & Treats is a newer addition to Alexandria’s Black business community. Brandon Byrd started with a vintage food truck before he purchased and transformed Commerce Street’s historic Ice House into a stunning 1950s-inspired custard shop. Locals line up around the block for fresh and creamy scoops of the Wisconsin-style frozen dessert and Goodies’ signature donut sandwich (an apple cider donut stuffed with vanilla frozen custard and topped with caramel).

“I always knew when I got into business that ownership is everything,” says the gregarious entrepreneur with a background in marketing. “The only way you are going to create a legacy is if you own it.”

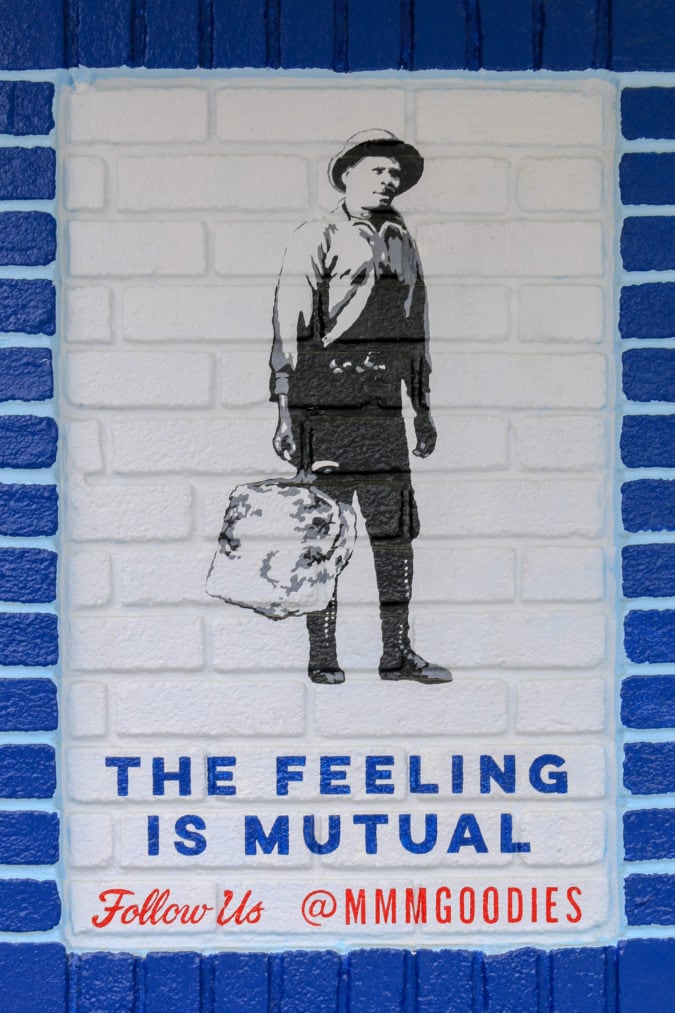

The original owner of the building was Mutual Ice Company, founded in 1900. Pointing to the illustration of a Black man holding a block of ice painted on Goodies’ front brick wall with the tagline, “The feeling is Mutual,” Byrd says he wanted the image to reflect the current ownership and the history of Black laborers in Alexandria.

“That picture is of an actual Black man,” he says. “I do things like that very subtly. You can give people accurate history without them even knowing it.”

If you go

Manumission Tour Company offers tours highlighting Alexandria’s Black history on Juneteenth and beyond. Tickets are $15 per adult and $12 per child.