Turning off the smooth pavement of Highway 136 and onto the sun-baked gravel road, the only inclination that I’m on the right track is a small, forgettable street sign marking Cerro Gordo Road. As I make my way up the hill, I don’t see a single hint of the town that awaits. The road abruptly angles back and forth, narrowly cutting through columns of rust-colored rock and shifting sand, masking anything more than 20 feet ahead.

The drive itself has become an adventure I wasn’t prepared for. At times, I feel like the car is mere centimeters from slipping off the edge and plummeting hundreds of feet down a rocky slope. But as Helen Keller once famously said, “Life is a daring adventure or it is nothing at all.” So, after eight miles of pinched roads and a mile of elevation gain, I finally round the last turn and my real adventure opens up before me. There it is in all its rusted glory: the hidden ghost town of Cerro Gordo.

What Los Angeles is, is due to Cerro Gordo

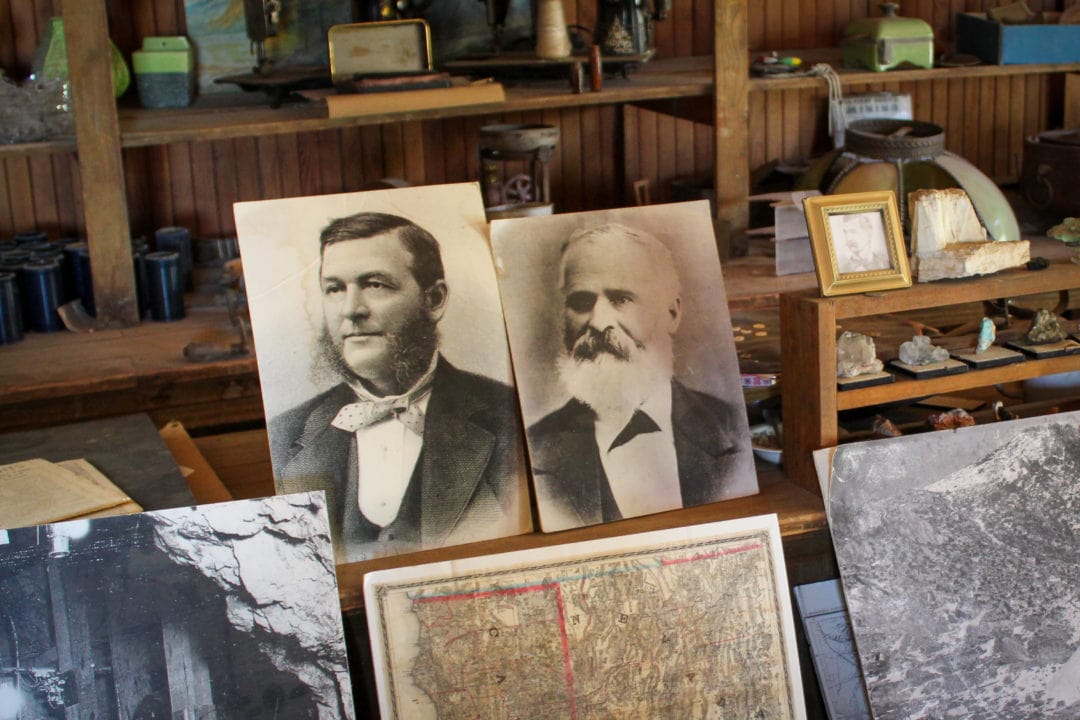

Cerro Gordo got its start back in 1865 when a man named Pablo Flores started mining silver from the large hills that overlooked the Owens Valley in California (Cerro Gordo means “fat hill” in Spanish). But the quantity and quality of silver being harvested from these hills wasn’t kept secret for long. Local businessmen Victor Beaudry and Mortimer Belshaw caught wind of the riches and began acquiring mining claims in the area.

Beaudry and Belshaw eventually took over the entire property in 1869 and turned it into the largest producer of silver and lead in California. In that same year, The Los Angeles Times wrote: “What Los Angeles is, is mainly due to Cerro Gordo. It is the silver cord that binds our present existence. Should it be uncomfortably severed, we would inevitably collapse.”

“What was once the shimmering jewel of the Owens Valley had quickly turned into a sunburnt wasteland.”

Over the next 50 years, silver, lead, and zinc were religiously mined from the hills. And by 1900, roughly $17 million in precious minerals had come from Cerro Gordo (adjusted for inflation, that number is closer to $50 million today). Much more than just a mining den in the mountains, Cerro Gordo had blossomed into a fully functioning town, including 4,000 residents, 100 outhouses, seven saloons, and three brothels.

But like so many mining towns before it, once the money-making resources dwindled and natural water supplies dried up, the residents started to move on. And by 1938, Cerro Gordo had officially become a ghost town. What was once the shimmering jewel of the Owens Valley had quickly turned into a sunburnt wasteland.

But it wasn’t destined to stay that way forever…

“We’re not refurbishing a ghost town”

In June 2018, after being privately owned by one family for decades, Cerro Gordo officially went up for sale. And for $1.4 million, the town—and all of its buildings, outhouses, mines, and history—was sold to two friends, Brent Underwood and Jon Bier.

“Our goal is to figure out how we can keep Cerro Gordo authentic without making it into a museum,” Bier tells me, explaining why this purchase was so unique. “We want to keep the story and keep the integrity, but we’re not refurbishing a ghost town. We’re building something new with these amazing bones that we’ve been given.”

Underwood and Bier have officially owned Cerro Gordo for one year now—the deal was finalized on Friday, July 13, 2018. And since that freaky Friday, the friends admit they haven’t done a whole lot to the property.

“We were up there most of last summer after we bought it. But we didn’t really do a lot,” says Bier. “We explored mostly. Not just the land itself and the structures that are on it, but the houses were all furnished. The pictures were all there, the clothing was all there. Obviously there was a lot of junk and garbage and gross things, but then there were also a lot of gems.”

Some of these gems included tintypes from the 1800s, thousands upon thousands of antiques, and even some unopened whiskey bottles.

But as Bier mentioned, the new vision for Cerro Gordo is not to simply refurbish the past but to carry the town into a new day. Over the course of its history, the town has seen many different phases—history books chapterize its past into things like the Gordon Era (when silver was first discovered there) and the Zinc Era (when zinc ores mined from the hills proved to have commercial value). And for Underwood and Bier, they merely view themselves as the town’s next era.

“I think Jon and I are just the newest members of this historical lineage,” says Underwood. “We went up there and we saw that this town could be something more, something really special, and we’re excited to see that through.”

California’s own Emerald City

The second I set foot out of the car, I can almost feel the magic that Underwood and Bier described. Cerro Gordo appears out of nowhere. One moment you’re weaving your way through sandy turns, and the next you’re staring at the face of an old wooden mining hopper—something that looks eerily like a giant praying mantis. Beyond the bug-like hopper, there are countless other structures nestled among the hills. Bleeding into the surrounding terrain, I probably wouldn’t have noticed them all if the sun hadn’t been so high, allowing the tin roofs to reflect every heated glare.

So far, the place seems very Oz-like, and I’ve concluded this is my trying, yet magical, journey along a yellow road to reach California’s hotter and drier version of the Emerald City. I even have my own kind of Toto with me, albeit slightly larger and more goofy looking.

And if I’m Dorothy in this fictional tale, then 72-year-old Robert Desmarais is my very own Wizard of Oz.

Desmarais is not only a Cerro Gordo expert and author, but he has lived on the property for 22 years—the last nine have been full-time. Outfitted in a flannel shirt and a belt dripping with tools, Desmarais rolls up on an ATV to greet me and take me to the first spot on the property: the clubhouse.

“This is where all my tours start,” Desmarais says, as we enter through a doorway adorned by two rusted pickaxes. Since Cerro Gordo isn’t fenced off or gated, drivers will often wind their way up the long dirt road—either on purpose or by accident—and Desmarais is always there to greet them and offer directions or a spontaneous tour.

“The town has had power since 1916,” he says, as the lights flick on inside the clubhouse. “It was all running on steam before that. But we still don’t have running water.”

Two of the buildings do have some running water, but Underwood and Bier (who Desmarais affectionately refers to as “the boys”) have plans to get consistent water to every structure this year. But for now, Desmarais is pretty much reliant on locals from the nearby town of Lone Pine to truck up dozens of containers of fresh water every two weeks.

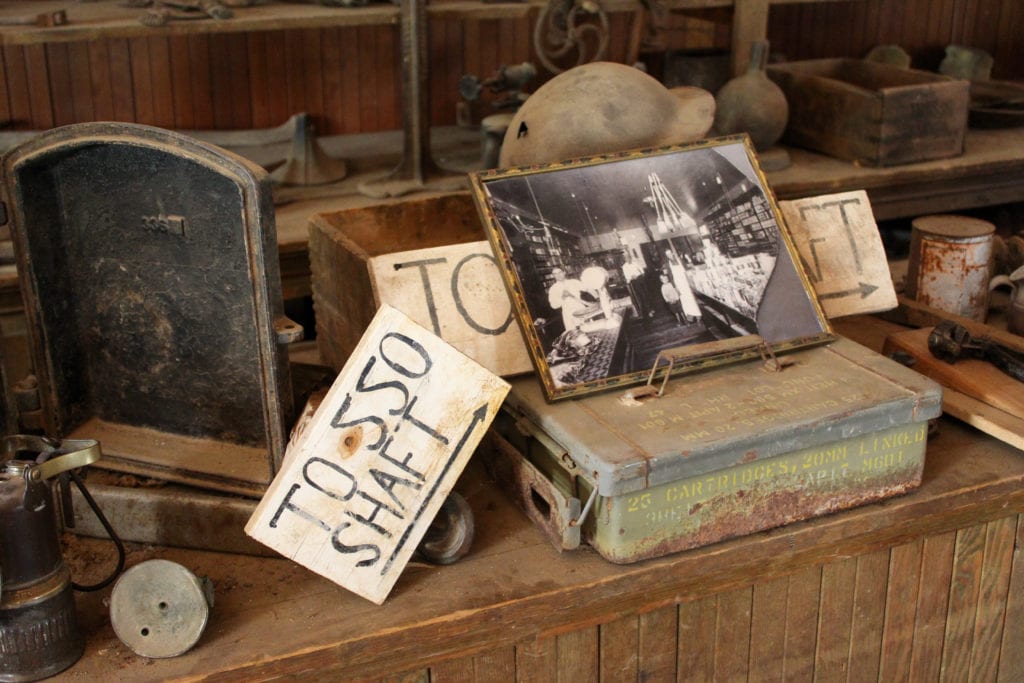

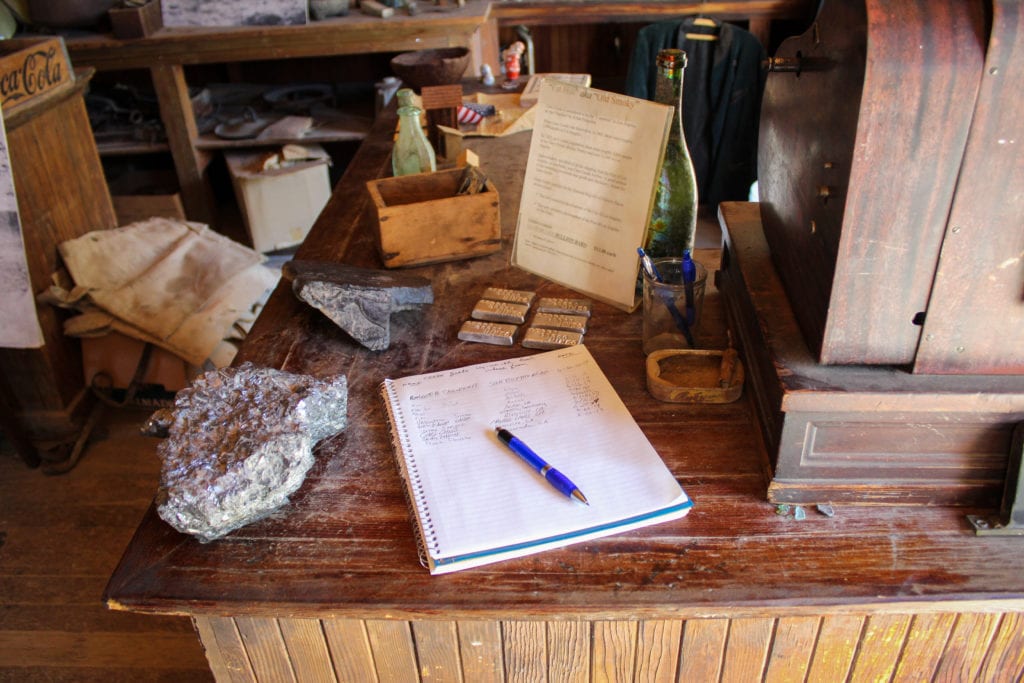

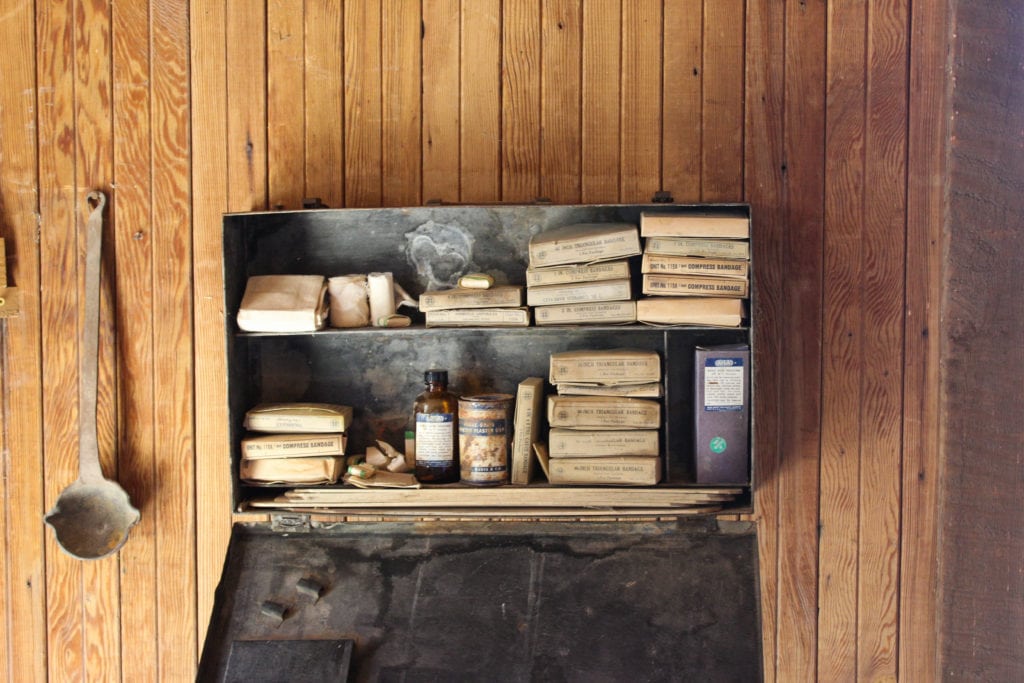

The clubhouse has numerous old pictures and mining artifacts. | Photo: Amanda Bungartz Everyone is encouraged to sign the guest book. | Photo: Amanda Bungartz An old cash register welcomes visitors to the clubhouse. | Photo: Amanda Bungartz A blue and yellow Cerro Gordo sign rests among the furnishings. | Photo: Amanda Bungartz Tiny details, like this amethyst doorknob, can be found throughout the property. | Photo: Amanda Bungartz An old medicine cabinet hangs in the mining cabin. | Photo: Amanda Bungartz

Moving from the clubhouse—which is packed with so many artifacts, photographs, and mining relics it’s hard to know where to focus—Desmarais and I make our way up to the mining cabin, and then back down to see the church, bunk house, and hotel. Along the way, I listen to a detailed recap of the entire property, as Desmarais rattles off names and dates of importance, mentioning them so easily you’d think they were part of his own kin.

Interestingly enough, I learn that the church is actually the most recent addition to the 337-acre property. Built in the late 1990s but made to resemble it’s much older neighboring structures, the little stained glass chapel acts as both a storage facility and a movie theater.

“During its prime, the town never had a church, schoolhouse, or jail,” says Desmarais. “The church was built by the former owner as a memorial to his wife, who died of cancer in 2001. She’s actually buried on the property.”

Halloween 2019

Walking among the rusted tools and original wooden buildings, I can see glimpses of the progress Underwood and Bier have begun to make and their touches of modernity—newly painted cornhole boards lean outside the clubhouse, a Casper mattress rests in one of the hotel bedrooms, and a bottle of Espolòn tequila sits atop the old bar. And while the two friends have tentative plans to put in a music studio and a spa, their ideas for the town seem to change regularly.

“This is evolving quickly. And because we’re open minded, the town is going to morph into exactly what it’s supposed to be,” says Bier. “But what that looks like right now is still undecided.”

“I think the more time we spend out there, the more the vision of the place is going to become clear to us,” Underwood adds.

While the exact use for each of the structures might be subject to change, one thing is for certain—Cerro Gordo plans to host people on Halloween.

“We’ve always said, from the day we bought Cerro Gordo, that we would do something around Halloween, 2019,” says Bier. “It might be a mixture of people camping and some staying in the properties that we have, but we will definitely do something that is on a more mass scale for Halloween this year.”

Beyond that, only time will tell what direction Cerro Gordo will go.

Left in good hands

After hours in the desert sun, once I’ve explored as much of the property as physically possible (omitting a few small lean-to structures that Desmarais warns might house a mountain lion), I must face the fact that my visit here is temporary and press on. After all, there’s no place like home.

But I feel at peace leaving knowing Cerro Gordo is in truly exceptional hands. Not only the new hands of two young entrepreneurs with a dream and a vision, but the old hands that have worked it, mined it, and protected it for over 20 years. As I go to leave, Desmarais thanks me for coming up and spending the day with him.

“I appreciate what you’re doing,” he says. “I love this place. And the more people that know about it, the more I hope they can learn to love it, too.”

It’s moments like this that stick with you—these rare glimpses of pure human heart and openness. It is for this I will return to Cerro Gordo again.

If you go

Cerro Gordo is located at the end of Cerro Gordo Road, right off Highway 136. Open every day from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m., Desmarais is usually available to give tours (there is a $10 suggested donation for the tour). We recommend calling ahead of time to schedule a visit.