Eileen Muza didn’t mean to buy a ghost town.

Muza was 29 years old and working at the Chicago Park District when she took a trip to Canyonlands National Park in Utah. On the flight, her seatmate recommended that she check out Cisco, a ghost town on the way from the airport to the park. When Muza arrived, she found early 20th-century shacks, a dilapidated post office, old buses and trucks, and heaps of trash.

Founded in the 1880s, Cisco, which sits near the Colorado border on a plain below the Book Cliffs, had been a railroad fill station. But like so many once-bustling towns in the West, it shriveled when the interstates came through and was officially abandoned by the 1990s.

Muza had never been to a ghost town before, but she started to imagine herself living there. “I tried to make it a rational decision,” she says. “I tried to make it okay in my mind. ‘Maybe it’s fine. I can always go home.’ I was getting older, I was going to be 30 and I saw the trajectory: I’m gonna be at this job forever. I wanted to test myself in a way and learn new things.”

And so, she bought Cisco.

From abandoned town to artists’ haven

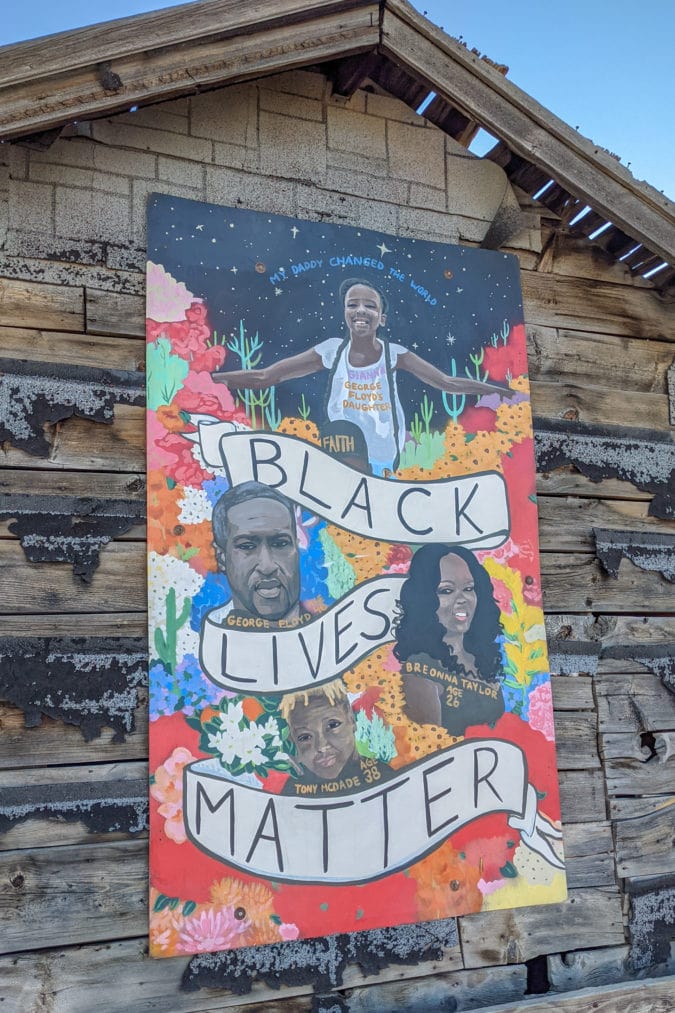

Since purchasing it in 2015, Muza’s lived in the ghost town, using salvaged and on-site materials to transform it from abandoned to an artistic space. Now, Cisco contains a welcome mural, designed by Muza and an artist friend; a renovated shed available to rent on Airbnb; a skatepark and snake sculpture wending through an abandoned bus; and a Winnebago and truck transformed into a residency where artists can work on their craft.

I learned about Muza from a friend who followed her efforts on Instagram, and I knew I had to find out what it was like for a woman my age to leave her urban life behind and transform a ghost town into a livable space.

I arrive in Cisco on Thanksgiving night, after driving all day through the harsh, otherworldly landscapes of Utah. Overhead is a dreamscape of clouds, a handful of stars, and a full moon; grass crackles beneath my boots. Buildings and objects appear out of the dark: A glowing red hen house, the shack where I’m staying, is marked by a splash of Christmas lights. I wake up in the night to use the outhouse and the wind is so loud for a moment I could swear that ghost riders are galloping through the field.

Projects everywhere

The next morning, I talk to Muza in the warmth of the sun on my porch. She says that this was one of the first structures she renovated; the uninsulated shack had been ravaged by mice and vandals. She cleaned it out, salvaged what she could, and then reinforced the walls, floors, and ceiling.

“I didn’t want to redo the place to not look like Cisco,” she says. “I wanted it to look like how it was, but I also wanted it to be clean, structurally sound, and beautiful.”

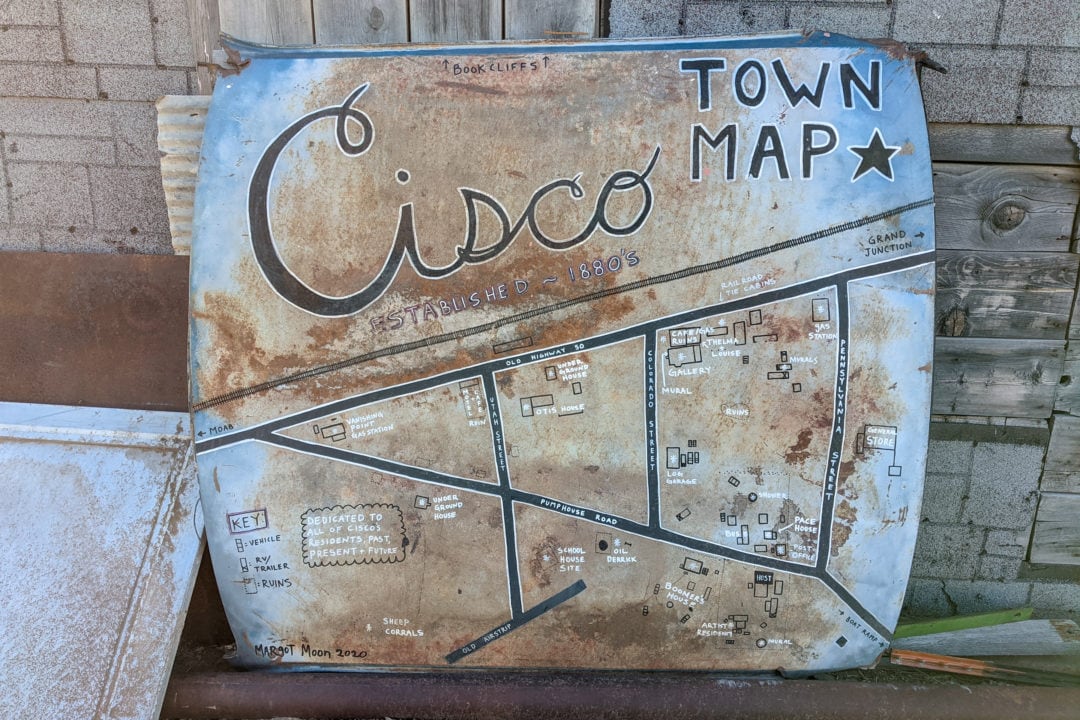

Muza had no experience in building or renovation before she moved to Cisco. She calls the time she’s spent here her “immersion school.” She taught herself to salvage so-called junk and use it to transform formerly-abandoned spaces into livable buildings. For Muza, using materials she finds on-site is key: A map of Cisco was made from a cut-off car roof, a fence from salvaged box springs. She also sources plenty of material for free. A local contractor gives her scraps of wood and stone, while a friend who works at nearby Arches National Park gave her some discarded windows from sheds.

Muza’s been hard at work here for years, but she still has big plans for the future. As we walk around, examining the spaces and artistic touches that make this ghost town special, Muza points out dilapidated structures and describes her plans. She’s working on transforming a shed into what she calls a “quarantine kitchen,” for friends who come to visit during the COVID-19 pandemic and want their own place to cook. The Cisco mural is an ongoing project; so is a teepee-like structure that she’s turning into a sauna. A red truck sitting in the field will soon be a bed for another artist residency, she hopes.

“Everywhere I look I see a project,” Muza says.

Rough potential

This sense of roughness and potential is part of what draws artists and adventurers to Cisco. Patrick Di Rito, a photographer from Atlanta, is finishing up his artist residency when I visit. He heard about Muza through a Vice documentary, struck up a friendship with her on Instagram, and then applied for the residency. He told me that Cisco’s communal nature and unpolished potential intrigued him.

“It felt like a space that was really raw,” he says. “If you propose something to Eileen and get her to approve it, you can probably do whatever you want. I like the idea of a space that’s flexible, not that established, you can do what you want to do there. In some ways it still feels like the Wild West.”

But that rawness also has its downsides. Di Rito says he underestimated how much energy it would take to just survive in Cisco. There’s no running water; in winter, Muza sets an alarm for every two hours through the night so she can wake up and feed her woodstove.

In addition to the physical demand, living in a ghost town can be emotionally taxing. One reason Muza moved to Cisco in the first place, she says, was to figure out whether she could live alone. She found that she loved it, spending her days completing tasks on her timetable, but part of what buoyed her was the friends who visited and the artists who came for the residency. When the pandemic began in March, she was scared at first and wondered if she would become too isolated.

There was also the question of money. Muza usually holds a big fundraiser every year, but COVID-19 tabled that for 2020; she now relies solely on donations and Airbnb guests.

Inspired by earthships

Cisco is dotted with signs asking tourists to take pictures from the road only; Muza recently erected a new fence to reinforce that request. She explains that while she wants people to experience this space, she also wants them to be respectful. She’s had busloads of tourists come through from Arches and wander into her house, a painstakingly restored log cabin.

“I can’t have scores of people every day coming through and seeing it like it’s an attraction,” she says. “I’m not trying to make this Disneyland for everybody else. I actually do live here. It’s a conflict that I’m still struggling with.”

Muza says if anything drives her out of Cisco before it’s done, it could be the near-constant stream of tourists. But for now, she says she’s still happy overall and committed to finishing the town—which means adding more spaces for artists, fixing up all of the outbuildings, and learning to build structures inspired by traditional homes from local Native cultures. When I mention earthships—the self-contained houses in places such as Taos, New Mexico—Muza’s face lights up. She stayed in an earthship once and says she still considers it to be the most inspiring place she’s ever seen—and that’s exactly what she wants her ghost town to be.

“How can I have this effect on people when they come to see what I’ve made?” Muza says about the earthships. “I hope when I finish what I’m doing here, it can have the same effect to some degree. I don’t have the funds to make it a big-scale thing, but who knows, maybe someday.”