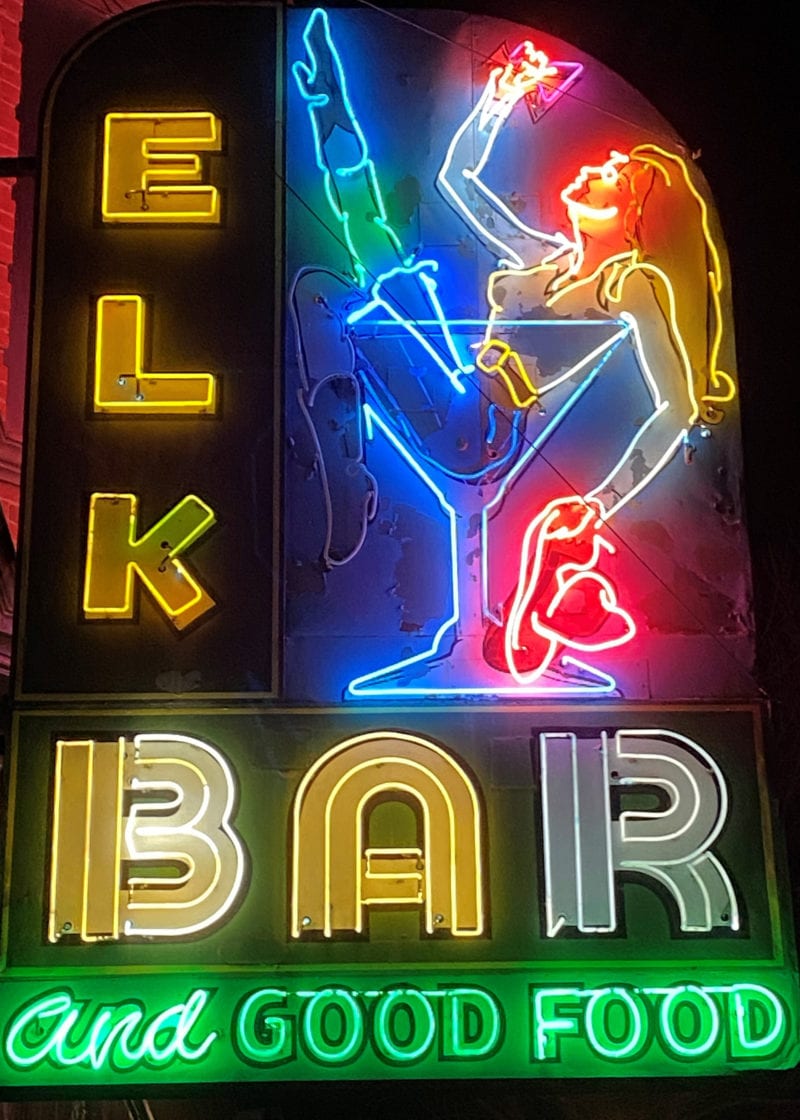

When Nita Magnuson returned to Chinook, Montana, for an all-class reunion in 1994, she noticed that the Elk Bar’s iconic neon sign was gone, leaving a terrible void on Indiana Street, the town’s main road. The once-scandalous “Lass in the Glass” sign (the G-rated version of its various local nicknames) had been sold when the bar closed.

Back when the lass was first hung above the Elk Bar—when it opened in 1948—the bar was on par with the post office or gas station: In the days before social media, it was a place for local farmers to get the latest news at the end of their work day.

Magnuson says that local men never had any issues with the Elk Bar’s scantily-clad mascot. Some of the women, on the other hand, were not impressed with the neon sign featuring a kicking, cocktail-swilling cowgirl advertising the bar and its “good food.” While their husbands caught up with the goings-on of Chinook inside the bar, the townswomen bounced from car to car, chatting with each other. Magnuson says her mom wasn’t a fan of the sign—but stuck in the back of the family car, Magnuson fondly remembers watching the lass kick and look woefully into her empty glass on a perpetual loop.

Life on the Hi-Line

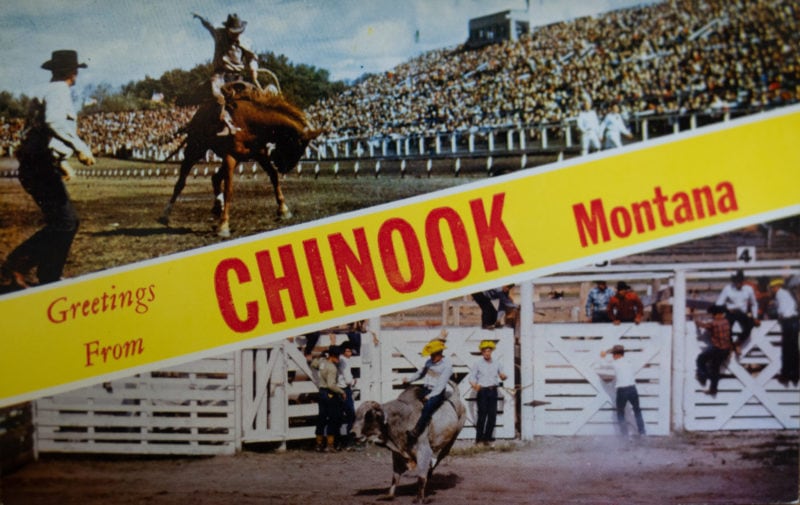

Chinook (population 1,230) is like many towns along Highway 2, a stretch referred to as the “Hi-Line.” Its full name, the Hi-Line Subdivision, speaks to the Great Northern Railroad tracks laid in the 1890s, the northernmost railway in the state.

The train was northern Montana’s lifeline, bringing in people, supplies, and, in later years, Sears catalog house kits. In the opposite direction, the railroad carried grain from the plains across the country. Driving along Highway 2, you’ll pass grain elevators in Glasgow, Malta, Zurich, and Havre. Legend has it that Chinook’s neighbors were named by a blind-folded railroader’s finger landing on a spinning globe—a scheme supposedly conjured up by the Great Northern Railroad’s owner, James J. Hill.

Chinook, on the other hand, was named for a natural phenomenon: the warm winter winds that can raise the temperature across the northern plains in a matter of hours, giving a bit of respite from the unforgiving cold.

Today, the town’s livelihood still centers around farming and agriculture, including grain, beef cattle, and sheep. Newer grain elevators stand at railroad tracks in Chinook; in nearby Zurich, old wooden elevators remain. Sugar beets and a sugar refinery are long gone (although the high school mascot is still a sugar beet) and have since been replaced by wheat, barley, canola, and chickpeas grown in windswept fields that stretch north to the Saskatchewan border and south to the Bears Paw Mountains.

A community effort

When Magnuson returned to Chinook in 1994 and found the lass gone, she and fellow Sugarbeeters (as Chinook residents are called) hatched a plan to find her and her stemware. “I felt this was a piece of Chinook history and we had to save it,” Magnuson says.

It didn’t take long to find it. When the Elk Bar’s equipment was sold the year before, the sign ended up in storage in Malta, 67 miles east of town on Highway 2. Magnuson made the first donation to the newly-formed “Lady in the Glass” committee of which she was also a member. Generous donations and interest-free loans to help buy the sign soon followed. But acquiring it was just the beginning of the community effort.

Decades after it was first hung, the lass was no longer kicking; her neon lights didn’t work and the sign was in such poor shape that she might easily have ended up in a salvage yard. More donations and fundraisers held over the next 16 years finally yielded enough money for her costly repairs.

In 2007, Max Hofeldt organized a lass look-alike contest held during the town’s annual Sugar Beet Festival. “We had quite a time finding a glass, but what I remember most is how completely disappointed my daughter was when she didn’t win,” Hofeldt says. The honor went to Bonnie Weber, who not only dressed the part while successfully posing in the glass (a concrete planter)—she also garnered the most donations within the hour she had to solicit bar patrons and festival attendees. “I don’t remember exactly what I won, but obviously, I got a lot of recognition,” Weber says with a laugh.

Ellen “Toots” McGillivray worked at the Elk Bar for years. When her daughter, Veronica Tabor, made a donation, she included a note and photo of her mother. “If my mom was still with us, I have no doubt that she would want to participate in this project,” she wrote. “Thank you so much for your efforts to restore and preserve ‘The Lady in the Glass.’ Chinook wouldn’t be Chinook without her to greet us.”

A star is re-born

The sign’s restoration also required a colossal effort. On the ground, the sign towered over those tasked with relocating it for repairs. Glass benders shaped new neon glass tubes over a flame, replacing the ones made by Clifford Anderson decades before. The sign was repainted, rewired, and eventually hauled back home on the two-lane highway. In 2010, the lass was rehung over the former Elk Bar (at the time a Goodies Galore general store) on Indiana Street. Local and Great Falls newspapers covered the day-long event.

Don and Jill Leo own the building that once housed the Elk Bar and currently operate the Mint Bar on the corner. While the Mint Bar’s sign is lit automatically each evening, the switch for the Lady in the Glass has to be flipped manually. The Leos turn it on for parades, weddings, and other special occasions, most recently for Anjanett Hawk, a photographer and recent Chinook transplant, to get a shot of the sign at night.

Now that the lass is back in her glass, Magnuson says she wants to build the Lady’s checking account so she can pay for her own “juice” (of the electrical variety—all that neon is an energy suck) and any additional “spiffing up” she may need in the future. But if the lass were to suddenly spring to life, her first concern would likely be to refill her glass—it’s been empty for far too long.