Iron, rock, wood, and mirrors help tell the story of African culture, heritage, and past at Dabls Mbad African Bead Museum. The museum, nestled in the outskirts of Detroit, Michigan, is a bright spot in an area that has been battered by years of abandonment and bankruptcy. Dedicated to a culture with roots some 8,000 miles away, the museum takes up an entire neighborhood block.

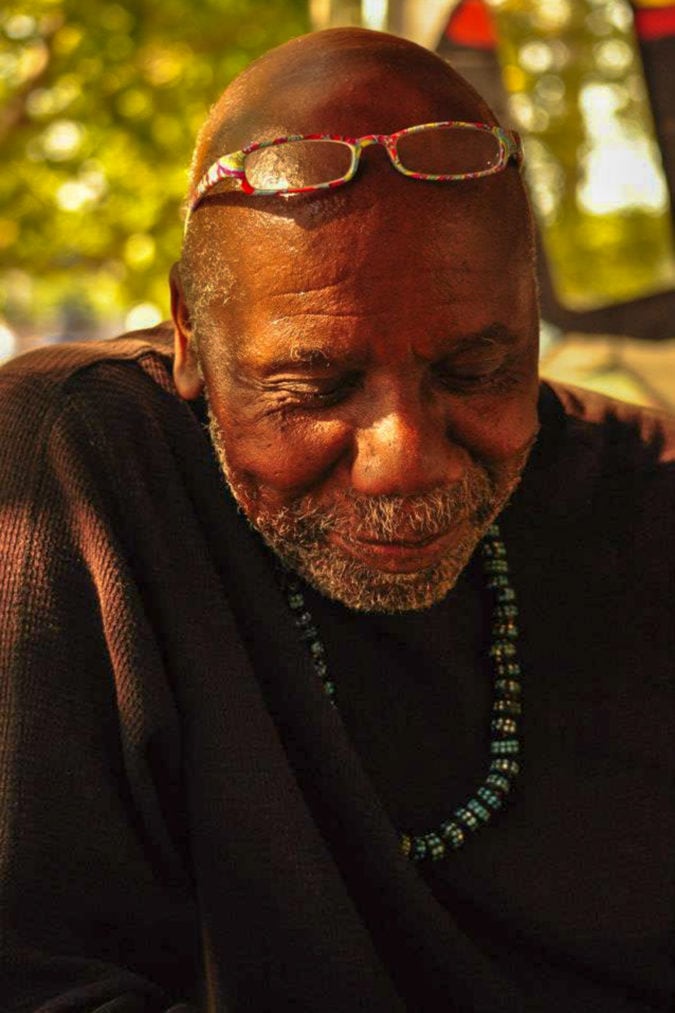

Museum owner and curator Olayami Dabls uses the four materials to spark emotions relating to the human condition. Dabls, who has worked as a visual storyteller for more than 45 years, crafted a giant sculpture park just outside the door of the museum, which is home to an impressive assortment of African beads.

“The museum has a way of making people feel comfortable,” Dabls says. “They come here and wander around late at night, even though it’s the most dangerous zip code in Detroit. But nothing [bad] has ever happened, because the community has embraced what we’re doing here.”

Dabls Mbad African Bead Museum is an attraction unlike no other in Detroit—or perhaps the world. It has the power to make drivers turn around, get out of their cars, and explore the area. Designed with loud, psychedelic colors, reflective glass, and twisted metal, the museum’s outdoor sculpture garden sits on a main street not far from the freeway. In fact, Dabls says that’s one of the goals of the museum—to inspire passing cars to stop.

“The installation is out there to attract people driving down Grand River Avenue,” he says. “I wanted people to stop and look around, take pictures, take videos, and send them back home.”

The museum’s mission makes sense in Motor City. Detroit is still shaped by the auto industry and operating a museum designed to pull in passersby was a strategic move that worked. Now, the museum is a hotspot for local photographers and creatives, and continues to grow in popularity as an internationally-renowned road trip destination for those looking to see a different side of the city.

Beads everywhere

Opened in 2002, Dabls Mbad African Bead Museum offers a stark contrast to its gray surroundings. The sprawling complex is colorful, evocative, and even jarring at times. Inside the museum, which is built within a century-old rowhouse, Dabls displays a massive collection of African beads amassed since the 1980s. Many hang from the walls or ceiling or sit inside of glass jars. Beads cover nearly every inch of the museum’s interior.

Beads play crucial roles in African cultures. They indicate wealth, tell stories about the wearer, and are used for physical and spiritual healing. In some countries, African beads were also historically used as a form of currency, exchanged for goods and other necessities. Yet as the demand for beads died down in recent decades, and people gravitated toward more traditional jewelry, Dabls saw two opportunities: to collect these timeless beads at a lower price, and to use them as a tool to help restore the connection between Black Americans and their African heritage.

Dabls, who was born in Mississippi and later moved to Detroit, worked in an African history museum while he built up his collection of beads. When he finally had enough to open his own museum—and when the land it now sits on became available—he saw a clear path toward his goal. “It outgrew the idea of a brick-and-mortar store,” he says.

Almost immediately, Dabls wanted to do more with the space. But it’s been an ongoing and laborious process to sculpt the land into his dream: to create a one-of-a-kind location that clearly tells the story of how African struggles have influenced modern-day Black America, in a city where the majority of its residents are Black.

It took 14 years to complete the sculpture park, which was finally finished in late 2016. Each sculpture tells its own story: A fence-like installation looks back at the African slave trade, and a mosaic mural covering the side of the museum is dedicated to the lives of African woman. But despite their clear purpose, people are still encouraged to leave with their own interpretations of the sculptures.

Mirrors and metaphors

The four materials used to craft the sculptures each carry their own symbolism. “I try to use materials that connect us to things that are before us,” Dabls explains. Mirrors, he says, are a way to look both into the past and the future. “When you’re looking in the mirror, we accept that we’re looking forward, but what we really see is what’s behind us,” he says.

He calls his work “anything but art,” a vehicle that gets people thinking about the human condition. It’s not meant to be easy to decipher or process. But Dabls hopes that visitors will walk away with a deeper understanding of different cultures.

Next, he aims to take that education one step further by developing an area dedicated to artifacts that further represent the African journey. It’s the latest step for the museum, which is meant to evolve over time. But one thing will stay the same—Dabls’ commitment to telling stories about the Black experience using iron, rock, wood, and mirrors.

“It’s quite obvious to me,” Dabls says, “that metaphors are the best way to teach.”