Hundreds of miles from the nearest dinosaur fossil dig, on a lakeshore that teemed with invertebrates during the Devonian Period, a forest of dinosaurs stands frozen in time. But pulling off US-23 into Dinosaur Gardens feels more like teleporting back to the 1950s, when Detroit motorists rounded up their families for a weekend escape to the small towns that dot Lake Huron’s shoreline.

Key Takeaways

- A 30-foot Jesus statue greets drivers, tying the park’s dinosaur displays to Domke’s Christian vision.

- Gary and Connie Stephens keep Dinosaur Gardens going, restoring displays and updating signs for their Ossineke community.

- Open from May 24 through October 14, the roadside park still welcomes visitors with towering, lifelike dinosaurs.

Dinosaur Gardens in Ossienke, Michigan: A Classic Roadside Attraction

Paul Domke opened Dinosaur Gardens in Ossineke, Michigan, in 1935. The business was built on a curious foundation of devout religion, scientific research, and figures made with a proprietary material called “cement plastics.” Next to the gift shop, Domke’s statue of Jesus Christ still looms large over the small parking lot. Inside the park, visitors can climb inside a giant Brontosaurus to view “The Greatest Heart,” a portrait of Jesus displayed alongside the dinosaur’s vital organs.

When I visit the park, I’m surprised by the enormity of the 30-foot statue. Facing the road, Jesus extends one hand, inviting drivers to stop, while the other holds a miniature planet Earth. Domke’s Christ may seem like an unlikely mascot for a dinosaur park, but a plaque next to his feet explains, “Mr. Domke’s religious philosophy maintained that Christ was the master planner of the Earth including the dinosaurs.”

New Owners, Refreshed Dinosaurs, and Updated Science

Although he was a devout Lutheran, Domke didn’t ascribe to the seven-day creation story in the Book of Genesis. He believed that the creation of the world occurred over millions of years and that Jesus, as the center of the universe, orchestrated the whole thing.

Since the 1930s, Dinosaur Gardens has only had a handful of owners. Gary and Connie Stephens, who also own a nearby cafe, never planned to take over Dinosaur Gardens. But when the park’s previous owner—and Connie’s Cafe regular—Frank McCourt approached them in 2013 about taking over his business, they decided to consider it.

Download the mobile app to plan on the go.

Share and plan trips with friends while discovering millions of places along your route.

“It’s a unique property,” Gary says. “We said it probably makes sense to keep it going because it’s important to Ossineke.” The Stephens embraced their new responsibilities, repainting derelict dinos and swapping outdated signage for Jurassic Park-style plaques with updated archaeological information.

Dinosaur Gardens was always meant to be more than just a roadside pitstop. The property represented Domke’s dream to educate families about dinosaurs, honor Jesus, and make a living in the process.

“Paul Domke was a very devotional man,” Gary says. “He tried to tie in evolution with his devotion, which is hard. I don’t know if he tried to find a real link between Christianity and the dinosaurs or if he did it to pull the park together.”

How the Dinosaurs Were Built: Steel Frames and “Cement Plastics”

Born in 1886, Domke had always been curious and artistic. After a stint at a naval hospital in Annapolis, Maryland, he started designing church altars in Detroit. But when the Depression hit, church decor became a luxury most congregations couldn’t afford. Out of work but brimming with ideas, Domke and his wife traveled north to Ossineke.

In 1930, the Domkes bought a plot of uncultivated land tangled with ferns, towering pines, and a burbling stream. It was the type of wild landscape where Domke envisioned a dinosaur might want to live. For the next 40 years, he poured his time, sweat, and money into the dinosaur park. Intent on creating accurate, life-size replicas, he traveled to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. He sketched fossils and skeletons, then used his medical knowledge to flesh them out with muscles and skin.

Domke pushed his knowledge and capabilities to the limit. In a 2002 interview, Roland Shaedig, Domke’s nephew, said that his uncle could be an exacting artist. When he first sculpted Jesus, he was unhappy with the craftsmanship of the statue’s right hand. To correct the wrong, Domke “propp(ed) some boards against our house windows … attached a stick of dynamite to the hand, blew it off, and started over.”

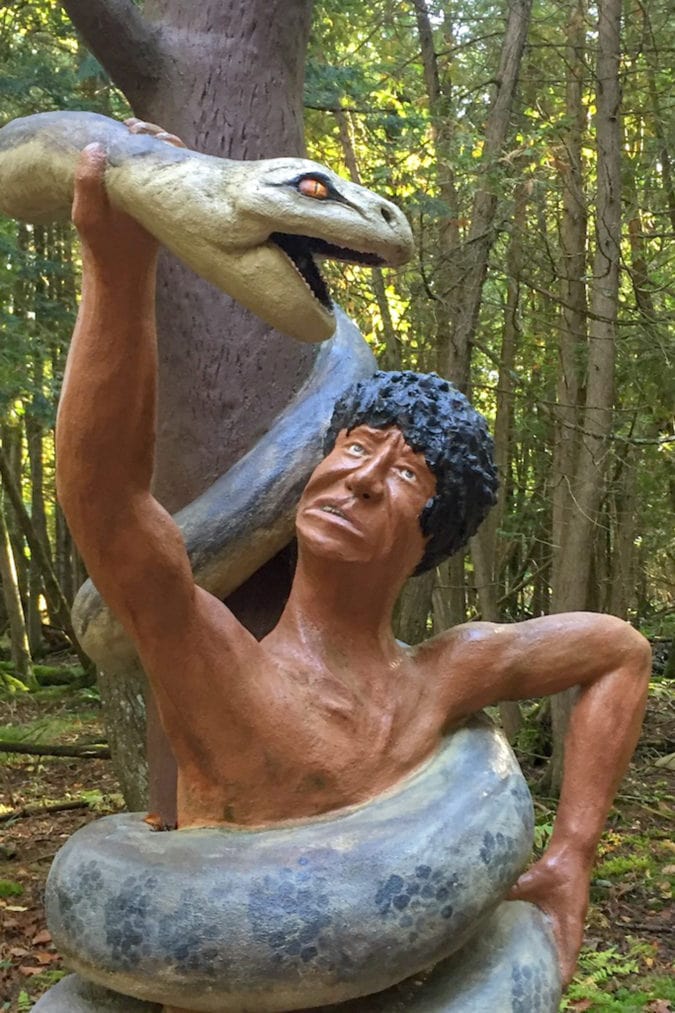

Once a design was finalized, Domke built his prehistoric beasts by forming plaster over steel frames. The first dinosaurs crumbled, so he enlisted the help of a local chemist to mix up a custom secret compound he called cement plastics. Whatever the mixture was, it worked. Now the Stephens and their team carefully strip paint from the dinosaurs to refinish them, keeping the underlying sculptures intact.

Gary once asked Domke’s nephew if his uncle had truly loved dinosaurs—or had he simply sensed an economic opportunity? “I wanted to find out why a man would devote 40 years of his life to build these dinosaurs,” Gary says. “The attention to detail, they look very real. You can see the backbone structures, the muscle tone, the sag in the skin, the flex in the arms and legs. I think it’s probably some of the best folk art I’ve seen anywhere in the United States when it comes to using cement.”

The two surmised that Domke saw a need for people to understand dinosaurs, mastodons, and ancient humans as real creatures, to see something beyond a few bones put together in a museum.

What to See on the Dinosaur Gardens Trail

Walking through Dinosaur Gardens on a crisp fall afternoon, I imagine Domke hard at work in the Michigan woods. Trees stand tall, ferns unfurl from fertile ground, and the stream ripples just as it did almost 90 years ago. The forest and its creatures are quiet and the sun streams through the trees, casting a spotlight onto the Stegosaurus.

Around the first bend in the pathway, a staircase leads visitors up into the Brontosaurus’ lofty neck. Inside its body cavity is a painting of Jesus nestled against the dinosaur’s heart and lungs. Down inside the tail, the Three Wise Men make an appearance. Domke’s touch is evident in each display, from dinosaurs to prehistoric lizards, to a scantily-clad cement-plastic man locked in mortal combat with a serpent.

Despite the outdoor elements and advances in science, Domke’s Dinosaur Park still thrives. Today it stands as a testament to an out-of-work church artist with enough faith to take his passion to new places. Domke wasn’t the first American to dream up a money-making Mesozoic menagerie, but it might be one of the last dinosaur parks left standing—at least if Gary Stephens has anything to do with it.

“There are very few roadside attractions like this anymore,” Gary says. “I have to say in reflection, it was probably one of the best purchases I’ve ever made. It has been a true pleasure owning Dinosaur Gardens.”

Plan Your Visit: Seasonal Hours and Dates

Dinosaur Gardens is open May 24 through October 14. Hours vary by season.