Like a lot of North America, Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula has four distinct seasons. But instead of “spring,” it’s more like “the season of anticipation” in early May when I follow Highway 132 around the finger of land jutting into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Soon the snow will melt, people tell me. Soon, the whales will return. Soon lobster fishing season will begin.

Early spring in northeastern Quebec is also not a traditionally Instagrammable season—the silver gray of a church steeple nearly disappears against the steel gray of the river or the taupe gray of the bare trees. The snow is brown with end-of-winter sand, and at times, the wind howls so fiercely that, as I try to get out of my car, I fear that it will blow the door right off.

But on a solo road trip in this quiet season, I have plenty of space to myself as I navigate the 90-year-old waterfront highway. There are few other visitors as I check out unusual sculptures sticking out of the river, explore thousands of fish fossils, and tour quirky local museums. I learn something of the region’s dark history, too. And along the way, as fishing boats begin to return with their spring catch, I eat as much fresh shrimp, seafood chowder, and lobster as I can.

Coffee and a chocolatine

I start my trip in Quebec City with coffee and a chocolatine (also known as a pain au chocolat or a chocolate croissant), crossing to the St. Lawrence’s south shore to pick up busy Highway 20. Local friends advise me to circle the peninsula counterclockwise, keeping the water on my right for better views, so at Mont-Joli, I turn inland onto Highway 132. When I reach Chaleur Bay, heading to Miguasha National Park, I get my first glimpse of the Gaspé’s red cliffs. At Quebec’s smallest national park, I learn that “Miguasha” means “red earth” in the Mi’kmaq language of the First Nations people whose traditional territory encompasses the Gaspé region.

Before people, though, there were fish. The park tells the story of the Devonian period (the “age of fishes”), when sea creatures evolved into organisms that walked on land. A park interpreter shows me dozens of well-preserved fossils of fish and primitive amphibians, most of which are casts of the originals that scientists dug from the surrounding cliffs.

In the waterside town of Carleton that evening, I wander into Bistro La Talle and find that I’m the only diner. The chef, who is blasting rap music, turns down the tunes low enough to tell me that it’s wild mushroom season. I opt for feuilleté aux champignons sauvages, a crisp pastry stuffed with mushrooms foraged nearby.

In the morning, at Musée Acadien du Québec in Bonaventure, I check out exhibits about the Acadians, who arrived from France in the 1600s. I learn about Le Grand Dérangement (or the Great Expulsion) in 1755, when the British evicted more than 6,000 Acadians by force. Many returned to Europe, while others made their way south to the U.S., establishing Louisiana’s Cajun community. Still others eventually came back to eastern Canada where their descendants live today.

Virtual seasickness

Back on Highway 132, I crest a hill and suddenly the Gulf of St. Lawrence spreads out below. When I pull into Percé, though, the inns are shuttered and “fermé” signs hang from closed shops and restaurants. A sign on the docks tells me that later in May, a tour boat could ferry me to Bonaventure Island, home to a colony of more than 100,000 gannets, a type of vibrantly hued sea bird. But today, at least I can glimpse the town’s other attraction: a famous rock. Rocher Percé, the “pierced rock,” is a slab of reddish limestone with a gravity-defying arch, carved by the sea.

After Percé’s eerie, off-season feel, I’m relieved that Bistro Bar Brise-Bise in the town of Gaspé is full, tables crowded with Gaspésie microbrews. I decide not to tackle the massive plates of seafood nachos, and instead dig into a crunchy salad layered with locally caught shrimp.

At Musée de la Gaspésie, a maritime history museum, I venture out on a surprisingly convincing virtual reality voyage on a 1960s fishing boat—I’m glad I’m not prone to seasickness when we hit rough seas, which are realistic enough that I grab the wall to steady myself.

I had hoped to hike to Land’s End in Forillon National Park, at the peninsula’s eastern tip. A hostel owner tells me that I could make it if I had snowshoes and trekked more than 20 kilometers (almost 12.5 miles) from the still-locked park gates. Without the proper gear, I decide to skirt the park instead, following Highway 132 around the end of La Gaspésie, beneath a sky that’s turned brilliantly blue. When I stop for a photo at Cap-des-Rosiers, Canada’s tallest lighthouse, the sea seems to extend forever, broken only by splashes of foam kicked up by the wind.

The first lobster of the season

Soon, the gulf hugs the road on one side and steep crags hem in the other, waterfalls of melting snow streaming down the boulders. A yellow caution sign warns of cascading winter ice, and another shows a wave inundating a car. Although the water seems fairly calm, I realize that if the surf were high enough to crash onto the roadway, there would be few places to escape.

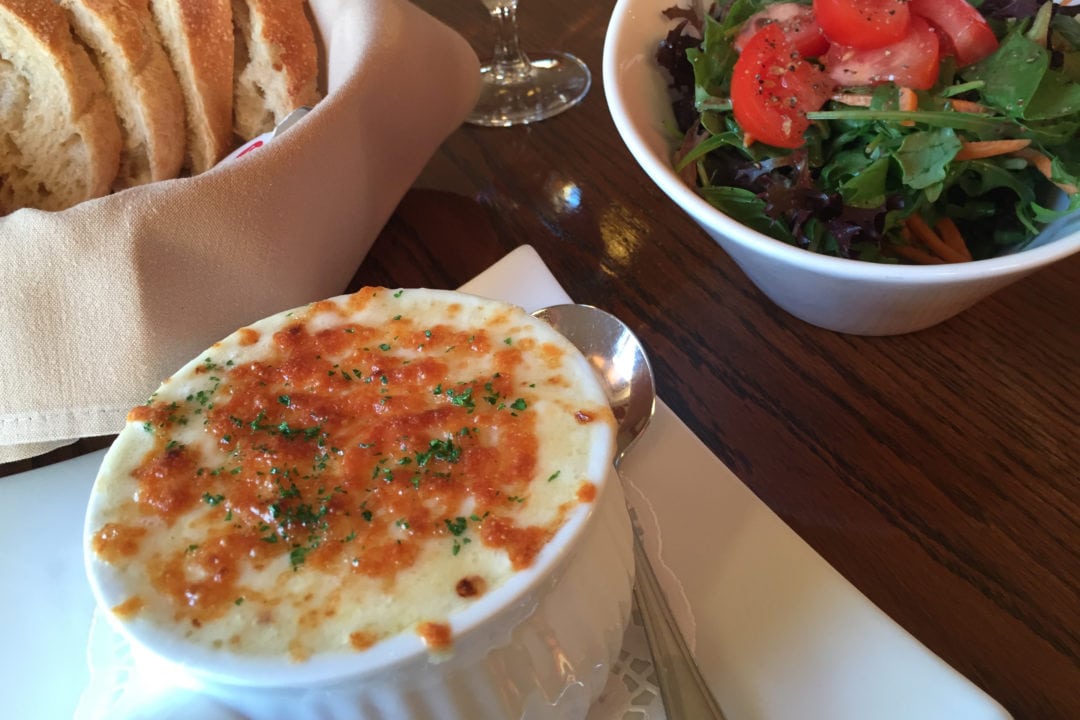

I tamp down my worry with a salmon and shrimp sandwich at a roadside auberge (French for an inn or restaurant), and, that evening in Sainte-Anne-des-Monts, with a soothing, deep crock of scallop and shrimp chowder, blanketed with gooey cheese.

As I continue west, the landscape—more farmland and less wild sea—begins to feel more settled. Yet the Gaspé still holds surprises. At the Centre d’Art Marcel Gagnon gallery in Sainte-Flavie, I marvel at more than 80 human-esque carvings that march out of the St. Lawrence and onto the sand.

I’ve passed several signs advertising homard (“Lobster! First of the season!”), so I pull in beneath the cartoonish giant crustacean at Capitaine Homard for a toasted bun stuffed with chunks of sweet meat.

Savor the solitude

Leaving the highway at Montmagny, I find Musée de l’accordéon, a 19th-century wooden house that contains anything you might want to know about, well, accordions. I listen to toe-tapping excerpts from the museum’s annual festival, and I discover how versatile the instrument is—it’s not just for your grandma’s polkas.

At Berthier-sur-Mer, I board a boat for a 45-minute crossing to Grosse Île and the Irish Memorial National Historic Site, an island where immigrants traveling to Quebec from Europe, particularly from Ireland, were forced to quarantine from 1832 to 1937 (similar to New York’s Ellis Island). A costumed nurse demonstrates how arrivals were sequestered for fear of cholera and a monument is etched with the names of those who didn’t survive their island isolation.

Back home, thinking about my Gaspé road trip after months of far less difficult pandemic quarantine, I can only imagine the lives of those immigrants, quarantined so far offshore. I realize that this quiet season journey helped me appreciate what I could still see and do—instead of focusing on all the things that I couldn’t. I didn’t hike to Land’s End or gawk at island seabirds, but on Quebec’s Gaspé Peninsula in this season of anticipation, I could still savor the scenery, the seafood, and the solitude.